Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

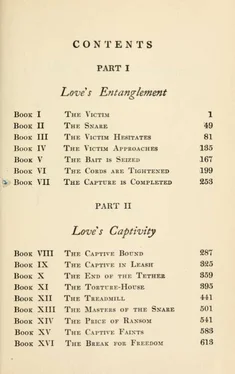

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The world was trying to crush it in him; the world hated it and feared it, and was bound that it should not live; and Thyrsis had sworn to save it—and so the issue was joined. He would hearten himself for the struggle—he would fling himself into the thick of it, again and again; he would summon up that thing which he called his Genius, that fountain of endless force that boiled up within him. Whatever strength they brought against him, he could match it; he might

be knocked down, trampled upon, left for dead upon the field, but he could rise and renew the conflict! He would talk to himself, he would call aloud to himself, he would repeat to himself formulas of exhortation, cries of defiance, proclamations of resolve. He would summon his enemies before him, sometimes in hosts, sometimes as individuals—all those who ever in his life had mocked and taunted him, scolded him and threatened him. He would shake his clenched fists at them; they might as well understand it—they could never conquer him, not all the power they could bring would suffice! He would call upon posterity also; he would summon his friends and lovers of the future, to give him comfort in his sore distress. Was it not for them that he was laboring—that they might some day feed their souls upon his faith?

Thyrsis would think of the "Song of Roland", recalling that heroic figure and his three days' labor: when he had read that poem, his heart had seemed to throb with pain every time that Roland lifted his sword-arm. He would think of the old blind "Samson Agonistes"; he would think of the Greeks at Thermopylae, of the siege of Haarlem. History was full of such tales of the agonies that men had endured for the sake of their faith; and why should he expect exemption, why should he shrink from the fiery test?

§ 16. So he lived and fought two battles, one within and one without; and little by little these two became merged in his imagination. He had conceived a figure which should embody the War; and that figure had come to be himself.

The War of which he was writing had come upon a people unsuspecting and unprepared; they had not

sought it nor desired it, they did not love it, they did not understand it. But the nation must be preserved; and so they set out to forge themselves into a sword. They had wealth, and they poured it out lavishly; and they had enthusiasm—whole armies of young men came forward. They were uniformed and armed and drilled, and one after another they marched out, with banners waving, and drums rolling, and hearts beating high with hope; and one after another they met the enemy, and were swallowed up in carnage and destruction, and came reeling back in defeat and despair. It happened so often that the whole land moaned with the horror of it —there was Bull Run and then again Bull Run, and there was the long Peninsula Campaign—an entire year of futility and failure; and there was the ghastly slaughter of Fredericksburg, and the blind confusion of Chancellorsville, and the bitter, disappointment of Antietam.

Thyrsis wished to portray all this from the point of view of the humble private, who got none of the glory, and expected none, but only suffering and toil; whose lot it was to march and countermarch, to delve and sweat in the trenches, to be stifled by the heat and drenched by the rain and frozen by the cold; to wade through seas of blood and anguish, to be wounded and captured and imprisoned, to be lured by victory and blasted by defeat. And into it all he was pouring the distillation of his own experiences. For there was not much of it that he had not known in his own person. Surely he had known what it was to be cold and hungry ; surely he had known what it was to be lured by victory and blasted by defeat. He had watched by the deathbed of his dearest dreams, he had listened to the moaning of multitudes of imprisoned hopes. He had known

what it was to set before him a purpose, and to cling to it in spite of obloquy and hatred; he had known what it was to suffer until his forehead throbbed, and all things reeled and swam before his eyes. He had known also what it was to sacrifice for the sake of the future, and to see others, who thought of no one but themselves, preying upon him, and upon the community, r.nd living in luxury and enjoying power.

Little by little, as he studied this War, Thyrsis had come upon a strange and sinister fact about it. Roughly speaking, the population of the country might have been divided into two classes. There were those to whom the Union was precious, and who gave their labor and their lives for it; they starved and fought and agonized for it, and came home, worn, often crippled, and always poor. On the other hand there were some who had cared nothing for the Union, but were finding their chance to grow rich and to establish themselves in the places of power. They were selling shoddy blankets and paper shoes to the government; they were speculating in cotton and gold and food. There were a few exceptions to this, of course; but for the most part, when one came to study the gigantic fortunes which were corrupting the nation, he discovered that it was just here they had begun.

So this was the curious and ironic fact; the nation had been saved—but only to be handed over to the

•/

money-changers! And these now possessed it and dominated it; and a new generation had come forward, which knew not how these things had come to be— which knew only the money-changers and their power. And who was there to tell them of the War, and all that the War had meant? Who was there to make

that titan agony real to them, to point them to the high destinies of the Republic?

Along with his war-books, Thyrsis was reading his daily newspaper, which came to him freighted with the cynicism of the hour. It was when the revelations of corruption in business and political affairs were at their flood; high and low, in towns and cities, in states and in the nation itself, one saw that the government of the country had been bought. Everywhere throughout the land Mammon sat upon the throne, and men cringed before him—there was only persecution and mockery for those who believed in the things for which America stood to all the world.

And this new Lord, who had purchased the people, and held them in bond, was extracting a toll of suffering and privation, of accident and disease and death, that was worse than the agony of many wars. The whole land was groaning and sweating beneath the burden of it; and Thyrsis, who shared the pain, and knew the meaning of it, was sick with the responsibility it put upon him, yearning for a thousand voices with which he might cry the truth aloud.

Some one must bring America face to face with its soul again; and who was there to do it—who was there that was even trying? Thyrsis had seen the statues of St. Gaudens, and he knew there was one man who had dreamed the dream of his country. But who was there to put it into song, or into story, that the young might read? Like the newspapers and the churches, the authors had sold out; they were writing for matinee-girls, and for the Pullman-car book-trade; and meantime the civilization of America was sliding down into the pit!

So here again was War! Here again were pain and

sickness, hunger and cold, solitude and despair, to be endured and defied; death itself to be faced—madness even, and soul-decay! Armies of men had gone out, had laid themselves down and filled up the ditches with their bodies, to make a bridge for Freedom to pass on. And the ditches were not yet full—another life was needed!

Nor must he think himself too good for the sacrifice; there had been greater men than he, no doubt, burned up in the Wilderness, and blown to pieces by the cannon at "Bloody Angle"; there had been dreamers of mighty dreams among them—and they were dead, and all their dreams were dead. And neither must he love his own too dearly; there had been women who had suffered and died in that War, and babes who had perished by tens of thousands; and they, too, had been born with agony, had been loved and yearned for, and wept and prayed for.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.