Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

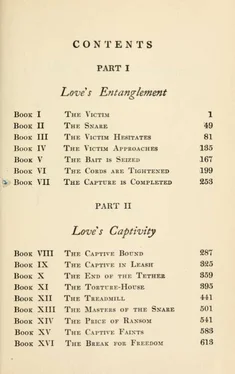

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The poem was simple and optimistic—it told of the beneficent qualities of rain, as it would appear to one whose roof did not leak. Somewhere in the course of it there was this stanza:

"I am the rain that comes at night, When all in slumber is folded light— Save one by weary vigils worn Who counteth the drops unto the morn."

This seemed to her an impressive bit, and she wondered what Thyrsis would think of it.

There were eight stanzas altogether, and when she finished the last of them the dawn was breaking, and it seemed hours since she had begun. As for the baby, he was still crying. She turned and peered at him; his eyelids drooped, and the crying came in spasms and gasps—it sounded very feeble, and a trifle perfunctory. Obviously he could not hold out much longer; Corydon would win, yes, she had won already. She lay still, andi thrills of happiness went through her. Was it the poem, or the thought of her release, and the nights of quiet sleep in the future?

When Thyrsis came in, an hour or two later, he found her huddled up in blankets on the floor of the living-room, her cheeks bright, her hair dishevelled. How fascinating she looked in such a guise! She was eagerly pondering her poem; and the baby was sleeping quietly, save for a few convulsive gasps, the last stragglers of his routed forces.

"And oh, Thyrsis," she exclaimed, "to-morrow night he will only cry half as long, and still less the next night. And soon he will go to sleep quietly like any well brought-up, civilized baby. And, my dear, I believe I'm going to be a poetess—I think that to-night I was really inspired!"

So he made haste to build a fire, and then came and sat and listened to the poem. How eagerly she waited for his verdict! How she hung upon his words! And what should a man do in such a case—should he be a husband or a critic? Should he be an amateur or a professional?

But even as he hesitated, the damage was done. "Oh,

you don't like it!" she cried. "You don't think it's good at all!"

"My dear," he argued, "poetry is such a difficult thing to write. And there are so many standards— a thing can be good, and yet not good! The heights are so far away "

"But oh, how can I ever get there," wailed Corydon, "if nobody gives me any encouragement?"

§ 9. THE time had now come for Thyrsis to put his job through. There was no longer any excuse for hesitation or delay. The book had come to ripeness in him; the birth-hour was at hand, and he must go and have it out with himself. He explained these things to Corydon, sitting beside her and holding her hands; they ascended once more to the heights of consecration; they renewed their vows of fortitude and faith, and then he went away.

For weeks thereafter he would be like the ghost of a man in the house, haggard and silent and preoccupied. All the work that he had ever done in his life seemed but child's play in comparison. Before this he had portrayed the struggles of men and women; but now he was to portray the agony of a whole nation—his heart must beat with the pulse of millions of suffering people. And the task was like a fiend that came upon him in the night-time and laid hold of him, dragging him away to sights of terror and madness. He was never safe from the thing for a moment—he could never tell when it might assail him. He might be washing the dishes, or wrestling with the refractory pump; but the vision would come to him, and he would wander off into the forest—perhaps to sit, crouching

in the snow, trembling, and staring at the pageant in his soul.

He lived in the midst of battles; the smoke of powder always in his nostrils, the crash of musketry and the thunder of cannon in his ears. He saw the cavalry sweeping over the plains, the infantry crouching behind intrenchments; he heard the yells of the combatants, the shrieks of the wounded and dying; he saw the mangled bodies, and the ground slippery with blood. New aspects of the thing kept coming to him—new glimpses into meanings yet untold. They would come to him in great bursts of emotion, like tempests that swept him away; and these things he had to wrestle with and master. It meant toil, the like of which he had never faced before, a tension of all his faculties, that would last for hours and hours, and leave him bathed in perspiration, and utterly exhausted.

A scene would come to him, in some moment of insight ; and he would drop everything else, and follow it. He would go over it, at the same time both creating and beholding it, at the same time both overwhelmed by it and controlling it—but above all things else, remembering it! He would be like Aladdin in the palace, stuffing his pockets with priceless jewels; coming away so loaded down that he could hardly stagger, and spilling them on every side. Then, scarcely pausing to rest, he would go back after what he had lost; he would grope about, gathering diamonds and rubies that he had all but forgotten—or perhaps coming upon new vaults and new treasure-chests.

So he would labor over a description, going over it and over it, not so much working it out, as letting it work itself out and stamp itself upon his memory. It made no difference how long the scene might be, he

would not write a word of it; it might be some battle-picture, that would fill thirty or forty pages—he would know it all by heart, as Demosthenes or Webster might have known an oration. And only at the end would he write it down.

Over some of the scenes in this new book he labored thus for two or three weeks at a stretch; there would be literally not a moment of the day, nor perhaps of the night, when the thing was not working in some part of his mind. He would think about it for hours before he fell asleep; and when he opened his eyes it would be waiting at his bedside to pounce upon him. If he tried for even a few minutes to rest, or to divert his mind to some other work, he would find himself ill at ease and troubled, with a sense as of something pulling at him, calling to him. And if anything came to interrupt him, then he would be like a baker whose oven grows cold before the bread is half done—it would be a sad labor making anything out of that batch of bread.

§ 10. AND this work he had to do as a married man, the father of a family and the head of a household; living with a child who was one incessant and irrepressible demand for attention, and a wife who was wrestling with weakness and sickness—eating out her heart in cruel loneliness, and cowering in the grip of fiends of melancholia and despair!

He had thought that when they moved into the new home, their domestic trials would be at an end. But now the cruel winter fell upon them. They had never known what a winter in the country was like; they came to see why the farmer had protested against their building in such a remote place. There were many days when they could not get to town, and some when they

could not even get to the farm-house. Also there was the pump, which was continually freezing, and necessitating long and troublesome operations before they could get any water.

It was, as fate would have it, the worst winter in the oldest inhabitant's memory. The farmer's well froze over on three occasions, and it had never frozen before, so he declared. For such weather as this they were altogether unprepared; they had only a wood-stove, and could not keep a fire all night; and the cheap blankets they had bought were made all of cotton, and gave them almost no protection. They would not sleep with the windows down; and so, for weeks at a time, they would go to bed with their clothing, even their overcoats on; and would pile curtains and rugs upon these—and even so, they would waken at two or three o'clock in the morning, shivering and chilled to the bone.

And in this icy room they would have to get up and build a fire; and it might be half an hour before they could get the house warm. Also, they had no facilities for bathing; and so little by little they began to lose their habits of decency—there were days when Corydon left her face unwashed, and forgot to brush her hair. Everyday, it seemed, they slipped yet further down the grade. Thyrsis would work until he was faint and exhausted, and then he would come over, and find there was nothing ready to eat. By the time that he and Corydon had cooked a meal, they would both of them be ravenous, and they would sit and devour their food like a couple of savages. Then, because they had overeaten, they would have to rest before they cleared things away; and like as not Thyrsis would get to thinking about his work, and go off and leave everything—and the dishes and the food might stay up on the table until

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.