Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

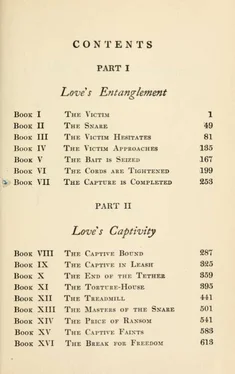

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

They prayed for fair days, and a little sunshine; and it seemed as if the weather-demons had discovered this, and were playing with them. There would come a bright morning, and they would spread a rug in the baby's cage, and hang out all their damp belongings to dry; and then would come a sudden shower, and baby and rug and belongings would all have to pile back into the tent. And then it would clear again, and everything would go out once more; and they would prepare dinner, and be comfortably settled to eat, when it would begin to sprinkle again. They would move in the clothing and the baby, and when it began to rain harder, they would move in

the table and the food; and forthwith the rain would cease. Because it was poor fun eating in a dark tent by lamp-light, amid the odor of gas-stove and cooking, they might move out once more—but only to repeat the same experience over again.

For six weeks after their arrival there was not a day without rain, and it would rain sometimes for half a week without ceasing. So everything they owned became damp and mouldy—all their clothing, their food, the very beds upon which they slept. One of their miseries was the lack of place to keep things; all their odds and ends had to be stowed away under the cots —where one might find clothing, and books, and manuscripts, and a hammock, and an umbrella, and some shoes, and a box of prunes, and a sack of potatoes, and half a ham. When water got in at the sides of the tent and wet all these objects, and the bedclothing hung over the floor and got into them, it was trying to the temper to have to rummage there.

•§ 2. BEFORE she left the city Corydon had taken the baby to consult a famous "child-specialist"—at five dollars per consultation; she had received the dreadful tidings that Cedric was threatened with the "rickets". So she had come out to the country with one mighty purpose in her soul. "Under-nourishment", the doctor had said; and he had laid out a regular schedule. Six times daily the unhappy infant was to be fed; and each time some elaborate concoction had to be got ready— practically nothing could be eaten in a state of nature. The first meal would consist of, say a poached egg on a piece of toast, and the juice of an orange, with the seeds carefully excluded; the next of some chicken broth with a cracker or two, and the pulp of prunes

with the skins removed; the next of some beef chopped up and pounded to a pulp and broiled, together with a bit of mashed potato or some other cooked vegetable; the next of some gruel, with cream and sugar, and some more prunes.

And these operations, of course, took the greater part of Corydon's day; she would struggle at them until she was ready to drop, and when she had to give up they would fall to Thyrsis. Some of them fell to him quite frequently—for instance, the pounding of the meat. It had to have all the fat and gristle carefully cut out; and there had to be a clean board, and a clean hammer, both of which must be scraped and washed afterwards; and whenever by any chance Cory-don let the meat stay on the fire a second too long, so that it got hard, the whole elaborate operation had to be gone over again—was not the baby's life at stake?

It was quite vain for him to protest as to the pains that Corydon took to remove every tiniest fragment of the skin of a stewed prune. "Surely, dearest," he would argue, "the internal arrangements of a baby are not so delicate as to be torn by a tiny bit of prune-skin !"

But to Corydon the internal arrangements of babies were mysterious things—to be understood only by a child-specialist at five dollars per visit. "He told me what to do," she would say; "and I am going to do it."

So she would prepare the concoctions, and would sit and feed them to the baby, spoonful by spoonful; and long after the little one had been stuffed to the bursting-point, she would hold the spoon poised in front of its mouth, making tentative passes, and seeking by some device to cajole the mouth into opening and admitting one last morsel of the precious nutriment. The child

had a word of its own inventing, wherewith it denoted things that were good to eat. "Hee, gubum, gubum!" he would exclaim; and Corydon would hold the spoon and repeat "Gubum, gubum,"—long after the baby had begun to sputter and gasp and make plain that it was no longer "gubum".

I Also, under the instructions of the specialist, they made an attempt to break the child of the "hoodaloo mungie" habit. A baby should lie down and go to sleep without handling, the authority had declared; and now that there was all outdoors for him to cry in, they resolved that he should be taught. So they built up the fence about the crib, and laid the baby in for his afternoon nap, and started to go away. And the baby gave one look of perplexity and dismay, and then began to cry. By the time they had got out of the tent he was screaming like a creature possessed; and Corydon and Thyrsis sat outside and stared at each other in wonder and alarm. When she could stand it no more, they went away to a distance; but still the uproar went on. Now and then they would creep back and peep in at the purple and choking infant; and then steal away ' again, and discuss the phenomenon, and wish that the "child-specialist" were there to advise them. Finally, when the crying had gone on for two hours without a moment's pause, they gave up, because they were afraid the baby might cry itself into convulsions. And so the "hoodaloo mungie" habit went on for some time yet.

Under the "stuffing regime" the infant at first thrived amazingly; he became fat and rosy, and Corydon's heart beat high with joy and pride. But then came midsummer, and the hot season; and first of all a rash broke out upon the precious body, and in spite of

powders and ointments, refused to go away. Later on came the "hives", with which the baby was spotted like the top of a pepper-crust. And then, as fate willed it, the family of a woman who did some laundry for Cory-don developed the measles; and Corydon found it out too late—and so they were in for the first of a long program of "children's diseases".

It was a siege that lasted for a month and more—a nightmare experience. The child had to be kept in a dark place, under pain of losing its eyesight; and when it was very hot in the tent, some one had to sit and fan it. It could not sleep, but writhed and moaned, now screaming in torment, now whimpering like a frightened cur—a sound that wrung Thyrsis' very heart. And oh, the sight of the little body—purple, a mass of eruptions, and with beads of perspiration upon it! Cory-don's mother came to help her through this ordeal, and would sit for hours upon hours, rocking the wailing infant in her arms.

§ 3. BUT there were ups as well as downs in this tenting adventure. There came glorious days, when they took long tramps over the hills; or when Thyrsis would carry the child upon his shoulder, and they would wander about the meadows, picking daisies and clover, and making garlands for Corydon. Once Cedric sat down upon a bumble-bee, and that was hard upon him, and perhaps upon the bee. But for the most part the little one was enraptured during these excursions. He was fascinated with the flowers, and continually seeking for an opportunity to devour some of them; while he was doing it he would wear such a roguish smile—it was impossible not to believe that he understood the agitation which these abnormal appetites occasioned in his

parents. Corydon would be seized with a sudden access of affection, and she would clutch him in her arms and squeeze him, and fairly smother him with kisses. Of course the youngster would protest wildly at this, and so not infrequently the demonstration would end tragically.

"I can't have any joy in my baby at all!" she would lament; and Thyrsis would have to soothe the child, and plead with her to find more practical ways of demonstrating her maternal devotion.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.