Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

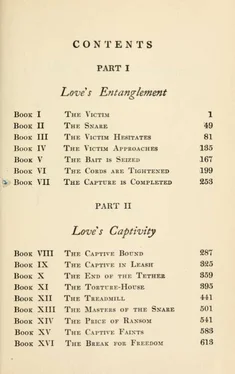

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

§ 2. So Thyrsis went away, carrying the burden of the scorn and contempt of every human soul he knew. It was in truth a dark hour in his life. He was at his wit's end for the bare necessities. He had reached the city with less money in his pocket than he had had the year before; and all the ways by which he had got

money seemed to have failed him at once. All the editors who published book-reviews seemed to have a stock on hand; or else to know of people whose style of writing pleased their readers better. And none of them seemed to fancy any ideas for articles that Thyrsis had to suggest.

Worst of all, the editor of the "'Treasure Chest" turned down the pot-boiler which he had been writing up in the country. He would not say anything very definite about it—he just didn't like the story—it had not come up to the promise of the scenario. He hinted that perhaps Thyrsis was not as much interested in his work as he had been before. It seemed to be lacking in vitality, and the style was not so good. Thyrsis offered to rewrite parts of the story; but no, said the editor, he did not care for the story at all. He would be willing to have Thyrsis try another, but he was pretty well supplied with serials just then, and could not give much encouragement.

Corydon had yielded to her parents and gone to stay with them for a while; and Thyrsis had got his own expenses down to less than five dollars a week—including such items as stationery and postage on his manuscripts. And still, he could not get this five dollars. In his desperation he followed the cheap food idea to extremes, and there were times when an invitation to an honest meal was something he looked forward to for a week. And day after day he wandered about the streets, racking his brains for new ideas, for new plans to try, for new hopes of deliverance.

In later years he looked back upon it all—knowing then the depth of the pit into which he had fallen, knowing the full power of the forces that were ranged against him—and he marvelled that he had ever had the

THE CAPTURE IS COMPLETED 259

courage to hold out. But in truth the idea of surrender did not occur to him; the possibility of it did not lie in his character. He had his message to deliver. That was what he was in the world for, and for nothing else; and he must deliver what he could of it. He would go alone, and his vision would come to him. It would come to him, radiant, marvellous, overwhelming ; there had never been anything like it in the world, there might never be anything like it in the world again. And if only he could get the world to realize it—if only he could force some hint of it into the mind of one living person! It was impossible not to think that some day that person would be discovered—to believe otherwise would be to give the whole world up for damned. He would imagine that chance person reading his first book; he would imagine the publishers and their advisers reading "The Hearer of Truth"— might it not be that at this very hour some living soul was in the act of finding him out? At any rate, all that he could do was to try, and to keep on trying; to embody his vision in just as many forms as possible, and to scatter them just as widely as possible. It was like shooting arrows into the air; but he would go on to shoot while there was one arrow left in his quiver.

§ 3. THYRSIS reasoned the problem out for himself; he saw what he wanted, and that it was a rational and honest thing for him to want. He was a creative artist, engaged in learning his trade. When he had completed his training, he would hot work for himself, he would work to bring joy and faith to millions of human beings, perhaps for ages after. And meantime, while he was in the practice-stage, he asked for the bare necessities of existence.

Nor was it as if he were an utter tyro; he had given proof of his power. He had written two books, which some of the best critics in the country had praised. To this people made answer that it was no one's business to look out for genius and give it a chance to live. But with Thyrsis it was never any argument to show that a thing did not exist, if it was a thing which he knew ought to exist. He looked back over the history of art, and saw the old hideous state of affairs—-saw genius perishing of starvation and misery, and men erecting monuments to it when it was dead. He saw empty-headed rich people paying fortunes for the manuscripts of poems which all the world had once rejected; he saw the seven towns contending for Homer dead, through which the living Homer begged his bread. And Thyrsis could not bring himself to believe that a thing so monstrous could continue to exist forever.

There was no other department of human activity of which it was true. If a man wanted to be a preacher, he would find that people had set up divinity-schools and established scholarships for which he could contend. And the same was true if he wished to be an engineer, or an architect, or a historian, or a biologist; it was only the creative artist of whom no one had a thought —the creative artist, who needed it most of all! For his was the most exacting work, his was the longest and severest apprenticeship.

Brooding over this, Thyrsis hit upon another plan. He drew up a letter, in which he set forth what he wanted, and stated what he had so far done; he quoted the opinions of his work that had been written by men-of-letters, and offered to submit the books and manuscripts about which these opinions had been written. He sent a copy of this letter to the president of each

THE CAPTURE IS COMPLETED

of the leading universities in the country, to find out if there was in a single one of them any fellowship or scholarship or prize of any sort, which could be won -by such creative literary work. Of those who replied to him, many admitted that his point was well taken, that there should have been such provision; but one and all they agreed that none existed. There were rewards for studying the work of the past, but never for producing new work, no matter how good it might be.

Then another plan occurred to him. He wrote an anonymous article, setting forth some of his amusing experiences, and contrasting the credit side of the "pot-boiling" ledger with the debit side of the "real art" ledger. This article was picturesque, and a magazine published it, paying twenty-five dollars for it, and so giving him another month's lease of life. But that was all that came of it—there was no rich man who wrote to the magazine to ask who this tormented genius might be.

Then Thyrsis, in his desperation, joined the ranks of the begging letter-writers. He would send long accounts of his plight to eminent philanthropists—having no idea that the secretaries of eminent philanthropists throw out basketsful of such letters every day. He would read in the papers of some public-spirited enterprise—he would hear of this man or that woman who was famous for his or her interest in helpful things— and he would sit down and write these people* that he was starving, and implore them to read his book. In later years, when he came to know of some of these newspaper idols, it was a»comfort to him to feel certain that his letters had been thrown away unread.

Also he begged from everybody he met, under whatever circumstances he met them, If by any chance the

person might be imagined to possess money, sooner or later would come some hour of distress, when Thyrsis would be driven to try to borrow. On one occasion he counted it up, and there were forty-three individual^ to whom he had made himself a nuisance. With half a dozen of them he had actually succeeded; but always promising to return the money when his next check came in—and always scrupulously doing this. There was never anyone who rose to the understanding of what he really wanted—a free gift, for the sake of his art. There was never anyone who could understand his utter shamelessness about it; that fervor of consecration which made it impossible for a man to humiliate him, or to insult him—to do anything save to write himself down a dead soul.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.