Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

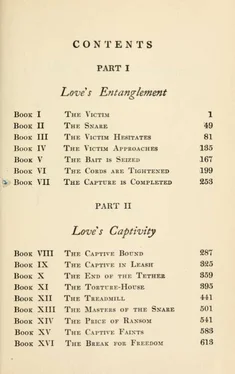

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

They had been butchered to make a holiday for the

readers of a yellow journal! "This is a wonderfully interesting world," the paper seemed to say—"well worth the penny it costs to read about it! Here on the first page is Antonio Petronelli, who cut up his- sweetheart with a butcher-knife, and packed her in a trunk. And here are seven people burned in a tenement-house; and an interview with Shrike, the plunger, who made three millions out of the wheat-corner. But most diverting of all are these two little cherubs who ran away and got married, and now want the world to support them while they write masterpieces of literature!"

And could not one see the great public devouring the tale—the Wall Street clerks in the cars, and the shopgirls over their sandwiches and coffee, and the loungers in the cafes of the Tenderloin! Could not one picture their smiles—not contemptuous, but genial, as of people who have learned that it is indeed an interesting world, and well worth the penny it costs to read about it!

§ 3. CORYDON shed tears of rage over this humiliation, and she wrote a letter full of bitter scorn to the newspaper woman. In reply to it came a friendly note to the effect that she had done the best thing in the world for them—that when they knew more about life and the literary game, they would recognize this!

The tangible results of the adventure were three. First there came a letter, written on scented note-paper, from a lady who commended their noble ideals and wished them success—but who did not sign her name. Second, there came a visit from a brother poet—a man about forty years of age, shabby and pitiful, with watery, light blue eyes and a feeble straggly moustache, and a manner of agonized diffidence. He stood in the doorway and shifted from one foot to the other, and

explained that he had read the article, and had come because he, too, was an unrecognized genius. He had written two volumes of poetry, which were the greatest poetry ever produced in English—Milton and Shakespeare would be forgotten when the world had read these volumes. For ten years he had been trying to find some publisher or literary man to recognize him; and perhaps Thyrsis would be the man.

He came in and sat on the bed and unwrapped his two volumes—several hundred typewritten pages, elaborately bound up in covers of faded pink silk. And Thyrsis read one and Corydon the other, while the poet sat by and watched them and twisted his hands nervously. His poetry was all about stars and blue-bells and moonlight, about springtime and sighing lovers, about cold, rain-beaten graves and faded leaves of autumn—the subjects and the images which have been the stock in trade of minor poets for two thousand years and more. Thyrsis, as he read, could have marked fifty phrases which were feeble imitations of things in Tennyson and Longfellow and Keats; and he read for half an hour, in the vain hope of finding a single vigorous line.

This interview was a very painful one. He could not bear to hurt the poor creature's feelings, and he did not know how to get rid of him. The matter was made still more difficult by the presence of Corydon, who did not know the models, and therefore thought the poetry was good. She let the visitor go on to pour out his heart; until at last came a climax that Thyrsis had been expecting all along. The man explained that he was a bookkeeper, out of work, and with a wife and three children on the verge of starvation; and then he tried to borrow some money from them!

The third result was the important one. It was a letter from a publishing-house.

"We are on the lookout for vital and worth-while books," it read, "and we are not afraid to venture. We have been much interested in the account of your work, and we should be very glad if you would give us a chance to read it immediately."

Thyrsis had never heard of this publishing-house, but that did not chill his delight. He hurried downtown with the manuscript, and came back to report. The concern was lodged in two small rooms in an obscure office-building. The manager, a Mr. Taylor, was a man not particularly prepossessing in appearance, but he was a person of intelligence, and was evidently interested in the book. Moreover he had promised to read it at once.

And that same week came the reply—a reply which set the two almost beside themselves with happiness. "I have read your manuscript," wrote Mr. Taylor. "And I have no hesitation in pronouncing it a work of genius. In fact, I am not sure but what it is the greatest piece of literature it has ever been my fortune as a publisher to come upon. It is vital, and passionately sincere, and I will stake my reputation upon the prophecy that it will be an instantaneous success. I hope that we may become the publishers of it, and will be glad if you will come to see me at once and talk over terms."

Thyrsis read this aloud; and then he caught Corydon in his arms, and tears of joy and relief ran down her cheeks.

He went to see the publisher, and for ten or fifteen minutes he listened to such a panegyric upon his book as made his cheeks burn. Visions of freedom and

triumph rose before him—he had come into his own at last! And then Mr. Taylor proceeded to outline his business proposition—and as Thyrsis realized the nature of it, it was as if he had been suddenly plunged into an Arctic sea. The man wanted him to pay one-half the cost of the plates of his book, and in addition to guarantee to take one hundred copies at the wholesale price of ninety cents per copy!

"Is that—is that customary in publishing?" asked the other.

"Not always," Mr. Taylor replied; "but it is our custom. You see, we are an unusual sort of publishing-house. We do not run after the best-sellers and the trash—we publish real books, books with a mission and a message for the world. And we advertise them widely —we make the world heed them; and so we feel justified in asking the author to help us with a part of the expense. We pay ten per cent, royalty, of course, and in addition the author has the hundred copies of his book, which he can sell to friends and others if he wishes."

"What would it cost for my book?" Thyrsis asked.

And the man figured it up and told him it could be done for about two hundred and fifty dollars. "I'll make it two hundred and twenty-five to you," he said —"just because of my interest in your future."

But Thyrsis only shook his head sadly. "I wish I could do it," he said, "but I simply haven't the money —that's all."

And so he took his departure, and carried his manuscript to another publisher, and then went home, crushed and sick.

§ 4. BUT the more Thyrsis thought of this plan, the more it came to possess him. If he could only get

that book printed, it could not fail to make its impression ! He had thought many times in his desperation of trying to publish it himself; and if he did that, he would have to pay the cost of the plates, of the printing and everything; whereas by this method he could get it for much less, and would have a hundred copies which he could send to critics and men of letters, in order to make certain of the book's being read.

When the manuscript came back from the next publisher, with a formal note of rejection, Thyrsis made up his mind that he would concentrate his efforts upon this plan. So he got down to another pot-boiler.

An old sea-captain had told him a story of some American college boys who had stolen a sacred idol in China. Thyrsis saw a plot in that, and the editor of the "Treasure Chest" considered it a "bully" idea. So he toiled day and night for a couple more weeks, and earned another hundred dollars. And then he did something he had never done in his life before—he went to some relatives to beg. He pleaded how hard he had worked, and what a chance he had; he would pay back the money out of the first royalties from the book— which could not possibly fail to earn the hundred dollars he asked for.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.