Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

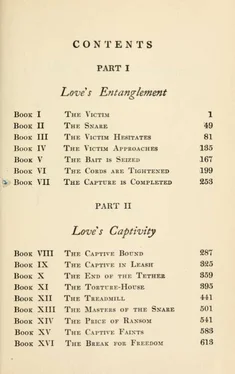

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Then there was another stumbling-block—the newspapers ! Thyrsis had to know what was going on in the world. He had learned to read the papers and magazines like an exchange-editor; his eye would fly from column to column, and he would rip the insides out of one in two or three minutes. To Corydon it was agony

to see him do this, for it took her half an hour to read a newspaper. She besought him to read it out loud—and was powerless to understand the distress that this caused him. He stood it as long as he could, and then he took to marking in the papers the things that she needed to know; and this he continued to do religiously, until he had come to realize that Corydon never remembered anything that she read in the papers.

This was something it took him years to comprehend ; there were certain portions of the ordinary human brain which simply did not exist in his wife. She had lived eighteen years in the world, and it had never occurred to her to ask how steam made an engine go, or what was the use of the little glass knobs on the telegraph-poles. And it was the same with politics and business, and with the thousand and one personalities of the hour. When these things came up, Thyrsis would patiently explain to her what she needed to know; and he would take it for granted that she would pounce upon the information and stow it away in her mind— just as he would have done in a similar case. But then, two or three weeks later, the same topic would come up, and he would see a look of sudden terror come into Corydon's eyes—she had forgotten every word of it!

He came, after a long time, to honor this ignorance. People had to bring some real credentials with them to win a place in Corydon's thoughts; it was not enough that they were conspicuous in the papers. And it was the same with facts of all sorts; science existed for Corydon only as it pointed to beauty, and history existed only as it was inspiring. They read Green's "History of the English People" in the evenings; and every now and then Corydon would have to go and

plunge her face into cold water to keep her eyes open. The long parliamentary struggle was utter confusion to her—she had no joy to watch how "freedom slowly broadens down from precedent to precedent." But once in a while there would come some story, like that of Joan of Arc—and there would be the girl, with her hands clenched, and hot tears in her eyes, and the fires of martyrdom blazing in her soul!

These were the hours which revealed to Thyrsis the treasure he had won—the creature of pure beauty whose heart was in his keeping. He was humbled and afraid before her; but the agony of it was that he could not dwell in those regions of joy with her—he had to know about stupid things and vulgar people, he had to go out among them to scramble for a living. So there had to be a side to his mind that Corydon could not share. And it did not suffice just to tolerate the existence of such things—he had to be actively interested in them, and to take their point of view. How else could he hold his place in the world, how could he win in the struggle for life?

This, he strove to persuade himself, was the one real difficulty between them, the one thing that marred the perfection of their bliss. But as time went on, he came to suspect that there was something else—something even more vital and important. It seemed to him that he had given up that which was the chief source of his power—his isolation. The center of his consciousness had been shifted outside of himself; and try as he would, he could never get it back. Where now were the hours and hours of silent brooding? Where were the long battles in his own soul? And what was to take the place of them—could conversation do it, conversation no matter how interesting and worth while?

Thyrsis had often quoted a saying of Emerson's, that "people descend to meet." And when one was married, did not one have to descend all the time?

He reasoned the matter out to himself. It was not Corydon's fault, he saw clearly; it would have been the same had he married one of the seraphim. He did not want to live the life of any seraph—he wanted to live his own life. And was it not obvious that the mere physical proximity of another person kept one's attention upon external things? Was not one inevitably kept aware of trivialities and accidents? Thyrsis had an ideal, that he should never permit an idle word to pass his lips; and now he saw how inevitably the common-place crept in upon them—how, for instance, their conversation had a way of turning to personality and jesting. Cory don was sensitive to external things, and she kept him aware of the fact that his trousers were frayed and his hair unkempt, and that other people were remarking these things.

Such was marriage; and it made all the more difference to an author, he reasoned, because an author was always at home. Thyrsis had been accustomed, when he opened his eyes in the morning, to lie still and let images and fancies come trooping through his mind; he would plan his whole day's work in that way, while his fancy was fresh and there was nothing to disturb him. But now he had to get up and dress, thus scattering these visions. In the same way, he had been wont to walk and meditate for hours; but now he never walked alone. That meant incidentally that he no longer got the exercise he needed—because Corydon could never walk at his pace. And if this was the case with such external things, how much more was it the case with the strange impulses of his inmost soul! Thyrsis was now like a

hunter, who starts a deer, and instead of putting spurs to his horse and following it, has to wait to summon a companion—and meanwhile, of course, the deer is gone!

From all this there was but one deliverance for them, and that was music. Music was their real interest, music was their religion; and if only they could go on and grow in it—if only they could acquire technique enough to live their lives in it! This would take years, of course; but they did not mind that, they were willing to work every day until they were exhausted —if only the world would give them a chance! But alas, the world did not seem to be minded that way.

§ 8. THYRSIS had waited a week, and then written the second publisher, and received a reply to the effect that at least two weeks were needed for the consideration of a manuscript. And meantime his last penny was gone, and he was living on Corydon's money. It was. clear that he must earn something at once; and so he had to leave her to study and practice in her own room, while he cudgelled his brains and tormented his soul with hack-work.

He tried his verses again; but he found that the spring had dried up in him. Life was now too sombre a thing, the happy spontaneous jingles came no more. And what he did by main force of will sounded hollow and vapid to him—and must have sounded so to the editors, who sent them back.

Then he tried book-reviewing; but oh, the ghastly farce of book-reviewing! To read futile writing and sham writing of a hundred degrading varieties—and never dare to utter a truth about them! To labor instead to put one's self in the place of the school-girl

reader and the tired shop-clerk reader and the sentimental married-woman reader, and imagine what they would think about the book, and what they would like to have said about it! To take these little pieces of dishonesty to an office, and sit by trembling while they were read, and receive two dollars apiece for them if they were published, and nothing at all if one had been so lacking in cunning as to let the editor think that the book was not worth the space!

However, Thyrsis had cunning enough to earn the cost of his room and his food for two weeks more. Then one day the postman brought him a letter, the inscription of which made his heart give a throb. He ripped the envelope open and read a communication from the second publisher:

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.