Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

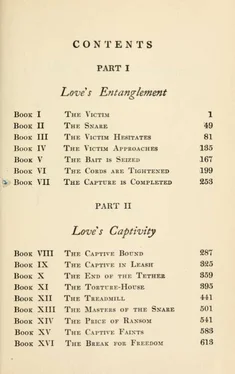

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Macintyre the elder was white-haired and rosy-cheeked. He had begun life as an emigrant-boy, running errands for a book-shop. In course of time he had become a partner, and then had started a cheap magazine for the printing of advertisements. From this had come the reprinting of cheap books for premiums ; until now, after forty years, Macintyre's was one of the leading publishing-concerns of the country. Recently the important discovery had been made that

the printing of half-inch advertisements headed "FITS" and "OBESITY' prevented the securing of full-page advertisements about automobiles. The former kind was therefore being diverted to the religious papers of the country, whose subscribers were now getting the "blood of the lamb" diluted with twenty-five per cent, alcohol and one and three-fourths per cent, opium. But such facts were not allowed to interfere with the optimistic philosophy of "Macintyre's Monthly".

The elder Macintyre seemed to Thyrsis the most naive and lovable old soul he had encountered in many a year. When he espied Thyrsis, he waited for no preliminaries, but went up to him as he stood by the fireplace, and put an arm about him, and led him off to a seat by the window. "I want to talk to you," said he.

"My boy," he went on, "I read that article of yours."

"Which one?" asked Thyrsis.

"The last one. And you know, Billy's got to stop putting things like that in the magazine!"

"What!" cried Thyrsis, alarmed.

"I won't have it! He must not print that article!"

"But he's accepted it!"

"I know. But he should have consulted me."

"But—but I wrote it at his order. And he promised to pay me "

"Oh, that's all right," said the old gentleman, with a genial smile. "We'll pay for it, of course."

There was a moment's pause, while Thyrsis caught his breath.

"My boy," continued the other, "that's a terrible article!"

"Um," said the author—"possMy."

"Why do you write such things?"

"But isn't it true, sir?"

Mr. Macintyre pondered. "You know," he said, "I think you are a very clever fellow, and you know a lot; much more than I do, I've no doubt. But what I don't understand is, why don't you put it into a book?"

"Into a book?" echoed Thyrsis, perplexed.

"Yes," explained the other—"then it won't hurt anybody but yourself. Why should you try to get it into my magazine, and scare away my half-million subscribers ?"

§12. THEY went in to dinner, which was served upon silver-plate, by the light of softly-shaded candles; and while the velvet-footed waiters caused their food to appear and disappear by magic, Thyrsis fulfiMed his mission and "threw Socialism" at the company.

The company had its guns loaded, and they went at it hot and heavy. The editors wanted to know about "the home" under Socialism; to which Thyrsis made retort by picturing "the home" under capitalism. They wanted to know about liberty and individuality under Socialism; and so Thyrsis discussed the liberty and individuality of the hundred thousand wage-slaves of the Steel Trust. They sought to tangle him in discussions as to the desirability of competition, and the impossibility of escaping it; but Thyrsis would bring them back again and again to the central fact of exploitation, which was the one fact that counted. They insisted upon knowing how this, that, and the other thing would be done in the Cooperative Commonwealth; to which Thyrsis answered, "Do you ask for a map of heaven before you join the Church?"

It was "Billy" Macintyre who brought up a somewhat delicate question; how would such an institution as "Macintyre's Monthly" be run under Socialism?

Thyrsis replied by quoting Kautsky's formula: "Communism in material production, Anarchism in intellectual". He showed how the state might print and bind and distribute, while men in "free associations" might edit and publish. But one could not get very far in this exposition, because of the excitement of the elder Macintyre. For the old gentleman was like a small boy who is being robbed of his marbles; if there had been a mob outside his publishing-house, he could not have been more agitated. He took occasion to state, with the utmost solemnity, that he disapproved of such discussions; and "Billy", who sat between him and Thyrsis, had to interfere now and then and soothe the "pater" down.

Mr. Macintyre's views on the subject of capitalism were simple and easy to understand. There could be nothing really wrong with a system which had brought so many great and good men into control of the country's affairs. Mr. Macintyre knew this, because he had played golf with them all and gone yachting with them all. And this was a perfectly genuine conviction; if there had been the slightest touch of sham in it, the old gentleman would have been more cautious in the examples he chose. He would name man after man who was among the most notorious of the country's "malefactors of great wealth"—men whose financial crimes had been proven beyond any possibility of doubting. He would name them in a voice overflowing with affection and admiration, as benefactors of humanity upon a cosmic scale; and of course that would end the argument in a gale of laughter. When the elder Macintyre entered the discussion, all the rest of the company moved forthwith to Thyrsis' side, and there were six Socialists confronting one business-man. And this

was a very puzzling and alarming thing to the old gentleman—his son and his magazine were getting away from him, and he did not know what to make of the phenomenon!

§ 13. THYESIS judged that the tidings must have got about that there was a new "lion" in town; for a couple of days after this he was called up by Comings, most popular of novelists, who asked him to have luncheon at the "Thistle" club. And when Thyrsis went, Comings explained that Mrs. Parmley Patton had read his book, and was anxious to meet him, and requested that he be brought round to tea. The other was tactless enough to let it transpire that he knew nothing about Mrs. Patton; but Comings was too tactful to show his surprise. Mrs. Patton, he explained, was socially prominent—was looked upon as the leader of a set that went in for intellectual things. She was interested in social reform and woman's suffrage, and was worth helping along; and besides that, she was a charming woman—Thyrsis would surely find the adventure worth while. Then suddenly, while he was listening, it flashed over Thyrsis that he had heard of Mrs. Patton before; the lady was in mourning for her brother, and Corydon had recently handed him a "society" item, which told of some unique and striking "mourning-hosiery" which she was introducing from Paris.

Thyrsis in former 3ays might have been shy of this phenomenon; but at present he was a collecting economist on the look-out for specimens, and so he said he would go. He met Comings again at five o'clock, and they strolled out Fifth Avenue together to Mrs. Patton's brown-stone palace. Thyrsis observed that his friend

had been considerate enough to omit his afternoon change of costume, and for this he was grateful.

Mrs. Patton was still in mourning, a filmy and diaphanous kind of mourning, beautiful enough to placate the angel Azrael himself. A filmy and diaphanous creature was Mrs. Patton also—one could never have dreamed of so exquisite a black butterfly. She was very sweet and sympathetic, and told Thyrsis how much she had liked his book—so that Thyrsis concluded she was not half so bad as he had expected. After all, she might not have been to blame for the hosiery story—it might even have been a lie. He reflected that the yellow journals no doubt lied as freely about young leaders of intellectual sets in "society" as they did about starving authors.

Mrs. Patton wanted to know about Socialism, and sighed because it seemed so far away. She made several remarks that showed real intelligence—and this was startling to Thyrsis, who would as soon have expected intelligence from a real butterfly. He got a strange impression of a personality struggling to get into contact with life from behind a wall some ten million dollars high. Mrs. Patton had three young children, and her husband was one of the "Standard Oil crowd"; she complained to Thyrsis that "Parmy"—so she referred to the gentleman—was always in terror over her vagaries.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.