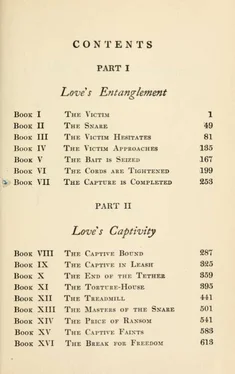

Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"It's like a steam-engine," said Thyrsis. "It doesn't matter how much power you get up, or how fast you make the wheels go—unless the switches are set right, you don't reach your destination."

"You only land in the ditch!" added Corydon. "And that's just the way I felt to-night—she'd take your argument every time, and dump it into a ditch. And she'd see it there, and not care."

"She doesn't care about facts at all, Corydon. And notice this also—she doesn't care about succeeding.

That's the thing you must get straight—her religion is a religion of failure! It comes back to that criticism of Nietzsche's—it's a slave-morality. The world be-

*/

longs to the devil; and the idea of taking it away from the devil seems to be presumptuous. Even if it could be done, the attempt would be "unspiritual'; for the 'world' is something corrupt—something that ought not to be saved. So you see, she's perfectly willing for the Belgians to have the rubber."

" 'Render unto Csesar the things that are Csesar's'!" quoted Corydon.

"Yes, and let Caesar spend them on Cleo de Merode. What she wants is to save the souls of her savages— to baptize them, and to perish gloriously at the work, and then be transported to some future life that is worth while. So you see what the immortality-mongers do with our morality!"

"Ah!" cried Corydon, swiftly. "But that need not be so!"

"But it is so!" he answered.

"No, no!" she protested. "You must not say that! That is giving up—and I felt such a different mood in you to-night! I wanted to tell you—we must do something about it, Thyrsis! It made me ashamed of my own life. Here I am, failing miserably—and all that work crying out to be done! I don't think I ever had such a sense of your power before—the things you might do, if only you could get free, if only I didn't stand in your way! Oh, can't we cast the old mistakes behind us, and go out into the world and preach that message?"

"But, my dear," said Thyrsis, "that wouldn't appeal to you always. Your temperament "

"Never mind my temperament!" she cried. "I am sick

of it, ashamed of it; I want the world to hear that trumpet-call! I want you to break your way into the churches—to make them listen to you, and realize their blasphemy of life!"

She caught hold of him and clung to him; he could feel, like an electric shock, the thrill of her excitement. He marvelled at the effect his words had produced upon her—realizing all the more keenly, in contrast with Delia, what a power of mind he had here to deal with. "Dearest," he said, "I must put these things into my books. You must stand by me and help me to put them into my books!"

§ 6. DELIA GORDON went away to take up her work in the city; but for many months thereafter that missionary impulse stayed with them. They would find themselves seized with the longing to throw aside everything else, and to go out and preach Socialism with the living voice. They were still immersed in its literature; they read Bellamy's "Looking Backward", and Blatch-ford's "Merrie England", and Kropotkin's "Appeal to the Young". They read another book about England that moved them even more—a volume of sketches called "The People of the Abyss", by a young writer who was then just forging to the front—Jack London. He was the most vital among the younger writers of the time, and Thyrsis watched his career with eager interest. There was also not a little of wistful hunger in his attitude—he had visions of being the next to be caught up and transported to those far-off heights of popularity and power.

Also, they were kept in a state of excitement by the Socialist papers and magazines that came to them. There was a great strike that summer, and they fol-

lowed the progress of it, reading accounts of the distress of the people. Every now and then the pain of these things would prove more than Thyrsis could bear, and he would blaze out in some fiery protest, which, of course, the Socialist papers published gladly. So little by little Thyrsis was coming to be known in "the movement". Some of his friends among the editors and publishers made strenuous protests against this course, but little dreaming how deeply the new faith had impressed him.

In truth it was all that Thyrsis could do to hold himself in; it seemed to him that he no longer cared about anything save this fight of the working-class for justice. He was frightened by the prospect, when he stopped to realize it; for he could not write anything but what he believed, and one could not live by writing about Socialism. He thought of his war-book, for instance. It was but two or three months since he had finished it, and it was his one hope for success and freedom ; and yet already he had outgrown it utterly. He realized that if he had had to go back and do it over, he could not; he could never believe in any war again, never be interested in any war again. Wars were struggles among ruling-classes, and whoever won them, the people always lost. Thyrsis was now girding up his loins for a war upon war.

So there were times when it seemed that a literary career would no longer be possible to him; that he would have to cast his lot altogether with the people, and find his work as an agitator of the Revolution. One day a marvellous plan flashed over him, and he came to Corydon with it, and for nearly a week they threshed it over, tingling with excitement. They would sell their home, and raise what money they could, and

got themselves a travelling van and a team of horses, and go out upon the road on a Socialist campaign!

It was a perfectly feasible thing, Thyrsis declared; they would carry a supply of literature, and would get a commission upon subscriptions to Socialist papers. He pictured them drawing up on the main street of some country town, and ringing a dinner-bell to gather the people, and beginning a Socialist meeting, He would make a speech, and Corydon would sell pamphlets and books; they had animated discussions as to whether she might not learn to make a speech also. At least, he argued, she might sing Socialist songs!

Thyrsis was forever evolving plans of this sort; plans for doing something concrete, for coming into contact with the world of every day. The pursuit of literature was something so cold and aloof, so comfortable and conventional; one never pressed the hand of a person in distress, one never saw the light of hope and inspiration kindling in another's eyes. So he would dream of running a publishing-house or a magazine, of founding a library or staging a play, of starting a colony or a new religion. And then, after he had made himself drunk upon the imagining, he would take himself back to his real job. For that summer his only indiscretions were to buy several thousand copies of the "Appeal to Reason", and hire the old horse and buggy, and distribute them over some thirty square miles of country; also to help to organize a club for the study of Socialism at the university; and finally, when he was in the city, to make a fiery speech at a meeting of some "Christian Socialists." Because of this the newspaper reporters dug out the accounts of his earlier adventures, and "wrote him up" with malicious bantering. And this, alas—as the publisher pointed out—

was a poor sort of preparation for the launching of the war-novel.

Needless to add, the two did not fail to wrestle with those individuals whom they met. Thyrsis got a collection of pamphlets, judiciously selected, and gave them to the butcher and the grocer, the store-clerks and the hack-drivers in the town. But a college-town was a poor place for Socialist propaganda, as he realized with sinking heart; its population was made up of masters and servants, and there was even more snobbery among the servants than among the masters. The main architectural features of the place were fraternity-houses and "eating-clubs", where the sons of the idle rich disported themselves; once or twice Thyrsis passed through the town after midnight, and saw these young fellows reeling home, singing and screaming in various stages of intoxication. Then he would think of little children shut up in cotton-mills and coal-mines, of women dying in pottery-works and lead-factories; and on his way home he would compose a screed' for the "Appeal to Reason".

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.