Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

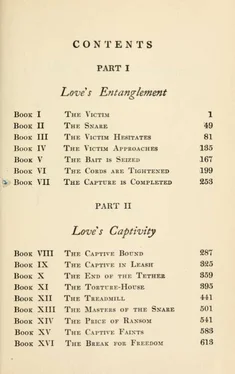

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

THE MASTERS OF THE SNARE 523

would be easy, now that he was free from the money-terror. But alas, it was not easy, and nothing could make it easy. If he had more energy, it only meant that his vision reached farther, and set him a harder task. Never in his life did he write a book, the last quarter of which was not to him a nightmare labor. He would be staggering, half blind with exhaustion— like a runner at the end of a long race, with a rival close at his heels.

Also, as usual, his stomach was beginning to weaken under the strain. He would come over sometimes, late in the afternoon, and lay his head in Corydon's lap, almost sobbing from weariness; and yet, after he had eaten a little and helped her with the hardest of her tasks, he would go away again, and work half through the night. There was nothing else he could do—there was no escaping from the thing; if he lay down to rest, or went for a walk, it would be only to think about it the whole time. He would feel that he was not getting enough exercise, and he would drive himself to some bodily tasks; but there was never anything that he could do, that he did not have the book eating away at his mind in the meantime. It was one of the calamities of his life that there was no way for him to play; all he could do was to take a stroll with Corydon, or to tramp over the country by himself.

He finished the book in May; and he knew that it was good. He sent it off to Mr. Ardsley, and Mr. Ardsley, too, declared himself satisfied, and sent the balance of the money. So Thyrsis sank back to get his breath, and to put back some flesh upon his skeleton. He was wont to say when he was writing, one could measure his progress upon a scales; every five thousand words he finished cost him a Shylock's price.

This summer was, upon the whole, the happiest time they had yet known. The book was scheduled to appear early in September; and they had money enough to last them meantime, with careful economy. Their little home was beautiful; they planted some sweet peas and roses, and Thyrsis even began to dig at a vegetable-garden. Also, it was strawberry-time, and cherry-time was near; nor did they overlook the fact that they lived in close proximity to a peach-orchard. These, perhaps, were prosaic considerations, and not of the sort which Thyrsis had been accustomed to associate with spring-time. But this he hardly realized—so rapidly was the discipline of domesticity bringing his haughty spirit to terms!

He built a rustic seat in the woods, where they might sit and read; he built a table beside the house, where the dishes might be washed under the blue sky; and he perfected an elaborate set of ditches and dykes, so that the rain-storms would not sweep away their milk and butter in the stream. He talked of building a pen for chickens—and might have done so, only he discovered that the perverse creatures would not lay except at the time when eggs were cheap and one did not care so much about them. He even figured on the cost of a cow, and the possibility of learning to milk it; and was so much enthralled by these bucolic occupations that he wrote a magazine-article to acquaint his struggling brother and sister poets with the fact that they, too, might escape to the country and live in a homemade house!

With the article there went a picture of the house, and also one of the baby, who had been waxing enormous, and now constituted a fine advertisement. The winter had seemed to agree with him, and the summer agreed with him even better. Thyrsis would smile now

THE MASTERS OF THE SNARE 525

and then, thinking of his ideas of martyrdom; it was made evident that one member of the family was not minded for anything of the sort. The parents might become so much absorbed in their soul-problems that they forgot the dinner-hour; but one could have set his watch by the appetite of the baby. Nature had provided him, among other protections, with a truly phenomenal pair of lungs; and whenever life took a course that was not satisfactory to him, he would roar his face to a terrifying purple.

He was one overwhelming and incessant outcry for adventure. He would toddle all day about the place, getting his "mungies" into all sorts of messes. He was hard to fit into so small a place, and there were times when his parents were tempted to wish that some phenomenon a trifle less portentous had fallen to their lot. But for the most part he was a great hope—a sort of visible atonement for their sufferings. He at least was an achievement; he was something they had done. And he could not be undone, nor doubted—he put all skepticism to flight. In his vicinity there was no room for pessimistic philosophies, for Weltschmerz or Karma.

Thyrsis would sit now and then and watch him at play, and think thoughts that went deep into the meaning of things. Here was, in its very living presence, that blind will-to-be which had seized them and flung them together. And it seemed to Thyrsis that somehow Nature, with her strange secret chemistry, had reproduced all the elements they had brought to that union. This child was immense, volcanic, as their impulse had been; he was intense, highly-strung, and exacting— and these qualities too they had furnished. Curious also it was to observe how Nature, having accomplished her purpose, now flung aside her concealments and de-

vices. From now on they existed to minister to this new life-phenomenon, to keep it happy and prosperous; and she cared not how plain this might become to them —she feared not to taunt and humiliate them. And they accepted her sentence meekly, they no longer tried to oppose her. Her will was become an axiom which they never disputed, which they never even discussed. No matter what might happen to them in future, the Child must go on!

§ 9. THYRSIS utilized this summer of leisure to begin a course of reading in Socialism—a subject which had been stretching out its arms to him ever since he had made the acquaintance of Henry Darrell. He had held away from it on purpose, not wishing to complicate his mind with too many problems. But now he had finished with history, and was free to come back to the world of the present.

There were the pamphlets that Darrell had given him, and there was Paret's magazine. Strange to say, the latter's reckless jesting with the philanthropists and reformers no longer offended Thyrsis—he had been travelling fast along the road of disillusionment. Also, there was a Socialist paper in New York—"The Worker"; and more important still, there was the "Appeal to Reason". Thyrsis came upon a chance reference to this paper, which was published in a little town in Kansas, and he was astonished to learn that it claimed a circulation of two hundred thousand copies a week. He became a subscriber, and after that the process of his "conversion" was rapid.

The Appeal was an "agitation-paper". Its business was to show that side of the capitalist process which other publications tried to conceal, or at any rate to

THE MASTERS OF THE SNARE 527

gild and dress up and make presentable. Each week came four closely-printed newspaper-pages, picturing horrors in mills and mines, telling of oppression and injustice, of unemployment and misery, accident, disease and death. There would be accounts of political corruption—of the buying of legislatures and courts, of the rule of "machines" of graft in city and state and nation. There would be tales of the manners and morals of the idle rich, set against others of the sufferings of the poor. And week by week, as he read and pondered, Thyrsis began to realize the absurd inadequacy of the placid statement which he had made to his first Socialist acquaintance—that the solution of such problems was to be left to "evolution". It became only too clear to him that here was another war —the class-war; and that it was being fought by the masters with every weapon that cunning and greed could lay hands upon or contrive. In that struggle Thyrsis saw clearly that his place was in the ranks of the disinherited and dispossessed.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.