Bruce Hood - The Domesticated Brain - A Pelican Introduction (Pelican Books)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bruce Hood - The Domesticated Brain - A Pelican Introduction (Pelican Books)» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, ISBN: 2014, Издательство: Penguin Books Ltd, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Domesticated Brain: A Pelican Introduction (Pelican Books)

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books Ltd

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:9780141974873

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Domesticated Brain: A Pelican Introduction (Pelican Books): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Domesticated Brain: A Pelican Introduction (Pelican Books)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Domesticated Brain: A Pelican Introduction (Pelican Books) — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Domesticated Brain: A Pelican Introduction (Pelican Books)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

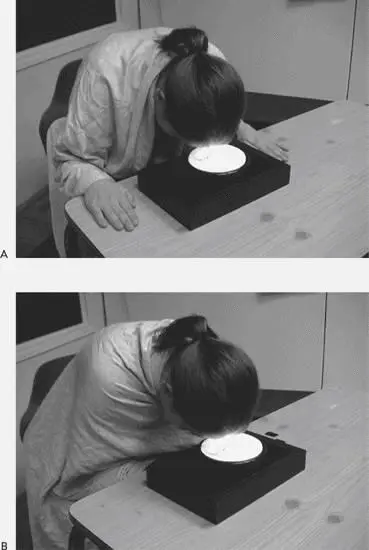

Older children will copy adults’ actions even when the children know the actions are pointless. 48In one study, preschoolers watched an adult open a clear plastic box to retrieve a toy. Some of the actions were necessary, such as opening a door on the front of the box, whereas other actions were irrelevant, such as lifting a rod that lay on the top. This behaviour is unique to humans. When presented with these sorts of sequences, children copied both the relevant and irrelevant actions whereas chimpanzees copied only those actions that were necessary to solve a task. The apes behaved in a way that was directed towards the goal of retrieving the reward, whereas for children, the goal was to faithfully copy the adult. Why would children over-imitate a pointless action? For the simple reason that children are more interested in fitting in socially with the adult than learning how to solve the task in the best possible way. 49

Figure 5: Hands-free adult activates switch in A, whereas adult’s arms are constrained in B (image courtesy of Gergely Csibra and György Gergely)

Developmental psychologist Cristine Legare at the University of Texas at Austin, thinks that this early blind imitation observed in children has profound implications for our species. Along with her anthropologist colleague Harvey Whitehouse from Oxford University, she has been looking at the origins of human rituals. 50Rituals are the activities that bind humans together – acts with symbolic significance that demonstrate that members of a group have shared values. All cultures have rituals for various events that are typically major transitions in life – birth, adolescence, marriage and death. These events punctuate our lives and are often associated with religious beliefs and ceremonies. The rituals themselves are typically inscrutable. There is no inherent logic to them. In that sense there are no causal laws operating, but if you don’t follow the rules then the ritual is violated. There is something about carrying them out in the correct way which gives rituals their potency. Likewise, Legare has shown that four- to six-year-olds are more likely to copy a behaviour step by step that has no obvious goal compared to one that does. In doing so, the child may be beginning to understand that there are some activities that others engage in that have no purpose but must be important precisely because they serve no obvious goal. 51

Getting into someone else’s head

You cannot directly see other people’s intentions, but you have to assume that they have them. This is called mentalizing – assuming that other people are intentional because they have minds. People are not random, but rather do things on purpose because they have goals that control their behaviour. In one study, 52twelve-month-olds watched an experimenter look at one of two stuffed animal toys and exclaim, ‘Ooh, look at the kitty!’ A screen was then lowered and raised to reveal the adult holding either the kitten or the other toy. If the adult was revealed holding the other toy, the babies looked longer – they were confused by her intentions. They interpret people as doing things for a reason. If mum is looking at the sugar bowl on the table, then she is likely to pick it up but not the salt-shaker that she has not been looking at. When mum looks at and then walks over to the fridge, she does so to open it. Infants are building up an expanding repertoire of contingencies – knowing that people behave in predictable ways. When babies think that something has a mind because it appears to act as if it has purpose, they will attempt to engage in joint attention. They will even copy a robot if it appears to have a mind. By simply interacting with a baby and responding every time the baby makes a noise or an action, the robot soon becomes an intentional agent, so that babies will actively try to engage the machine and even imitate its actions. 53

In contrast, animals do not imitate spontaneously as an attempt to initiate or engage in a social exchange. They may have the capacity for mentalizing, but invariably this is limited to situations that satisfy self-serving needs. For example, amorous male apes and monkeys will manoeuvre female partners out of the line of sight of dominant males in order to copulate surreptitiously. 54Many animals will steal food if they believe that others cannot see the theft. All of these abilities of perspective taking are heightened when there is potential danger from a competitor. However, it is not clear that these evasive actions really involve mentalizing. I know that I can avoid the strike of a snake if I approach from out of its line of sight in much the same way that I can avoid a tumbling boulder if I coordinate my actions correctly. In neither situation do I attribute mental states. I simply observe the actions and reason about what is relevant information. To establish mentalizing, there needs to be evidence of the attribution of beliefs – states of mind that individuals hold to be true about the world in the absence of any direct evidence. If I think you have a belief, then I assume that you hold certain expectations about the world to be true.

Even then, one could attribute belief to others simply by putting yourself in their shoes. For example, we can both separately enter and exit a hotel room and I can describe what I believe you saw based on my own experience. I would reason that because we both went into the same room, you must have seen what I saw. However, that need not be true. You might have had your eyes shut or something in the room might have changed, in which case I would be mistaken. For true mentalizing ability, you need to be able to understand that someone else might hold a different view from yours and indeed be completely wrong about the true state of the world. In other words, the litmus test for real mentalizing is the understanding that someone can hold a false belief .

Consider the following test. If I were to show you a confectionery box with ‘M&Ms’ written on it and ask you what is inside, then in all likelihood you would answer ‘M&Ms’. However, if I open it up to reveal pencils, then you should be a little surprised and possibly a little annoyed because you expected a chocolate treat. If I ask you what you originally thought was in the box, you would say ‘M&Ms’ because you understand that you had a false belief. This may seem trivially easy, but most three-year-olds give the wrong answer and claim that they thought there were pencils in the box. 55It’s as if they have completely rewritten history to fit with what they now know to be true. They do not understand that they held a false belief. Understanding that someone can be mistaken is part of a capability called theory of mind and children operate with an increasingly complex set of assumptions about the minds of others.

If three-year-olds do not understand that they were mistaken, then it is not too surprising that they are unable to attribute false beliefs to others. If I ask you what someone else will answer when posed the same question about what’s in the box, then you understand that they, too, should answer ‘M&Ms’. You can see things from their perspective and understand that they will also have a false belief. Again, three-year-olds give the wrong answer and say pencils. It’s as if they cannot easily take another person’s perspective.

When young children act in this self-centred view they are said to be egocentric because they view the world exclusively from their own perspective. If you show young children a model layout on a tabletop of a mountain range with different landmarks and buildings and then ask them to select a photograph that corresponds to the view they can see, three-year-olds correctly choose the one that matches their own perspective. However, when asked to choose the picture that corresponds to the view that someone else standing on the opposite side of the table can see, they typically choose again the photograph that matches their own. 56

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Domesticated Brain: A Pelican Introduction (Pelican Books)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Domesticated Brain: A Pelican Introduction (Pelican Books)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Domesticated Brain: A Pelican Introduction (Pelican Books)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.