Less than one and a half hours after the battle started, the Czech army had been beaten into its boots. Most of the soldiers that the Catholic forces captured alive were mercilessly butchered. Historians disagree about the number of Czech army soldiers killed, but several estimates speak about 9,000 men — out of an army that originally numbered 13,000. Among the battle’s victims were also a large number of Hungariansoldiers, who drowned when they tried to escape across the Vltava River in their combat gear. The Catholic League and the imperial army probably lost no more than 2,000 men.

So, what were the consequences of the disastrous Battle of White Mountain?

Early in the morning the day after the battle, King Bedřich — previously known as Prince Friedrich of Pfalz, whom the Czech nobility had elected their king a year earlier — fled the country with 300 members of his court and all the valuables they managed to stuff into their carriages. To many Prague burghers, who were eager to put up at least a symbolic fight against the Catholic forces, this was a tremendous disappointment.

“Now,” the historian Dvorský reports, “they witnessed their king and his men, who were to defend the nation, preparing for a humiliating escape. They bid him a most bewildered farewell.”

Unfortunately, this was not the last time in history when a leader of the Czech nation had to abandon his people at a moment when they were threatened from abroad. Just like unfortunate King Bedřich, President Edvard Beneš also fled the country after the tragic Munich Agreementin September 1938 (this time without the gold and jewels). Similarly, in 1968, when the Russiansand their Warsaw Pact comrades crushed the Prague Spring (see: Communism), all but one brave member of the Czechoslovak Communist Party’s Politburo signed the humiliating capitulation imposed by Moscow without grumbling.

Thus, the aftermath of the Battle of White Mountain was a symbolic preview of what some historians have described as the Czechs’ long-lasting misfortune in picking their leaders. It also marked the end of the independent Czech kingdom, which from that day on was politically reduced to a province within the Austrian empire. Typically, when Czech Euro-phobes in 2003 campaigned against membership in the EU, one of their slogans was “White Mountain — never again!”

The Emperor in Vienna, however, was not satisfied with only winning the battle. Half a year later, he decided to set a deterrent example by publicly executing 27 prominent Czechs in the Old Town Square. The rest of the population had to choose: either demonstrate loyalty to the Habsburg rulers by converting to Catholicism, or leave the country.

Here, too, exact figures are hard to obtain. Some estimates suggest that between 10 and 30 percent of the population, among them many of the Czech nation’s best and brightest, chose to leave their country, thus laying the foundation for the Czechs’ rich tradition as political emigrants.

The fact that the Catholic Church let itself be used by the Habsburgs in the aftermath of the Thirty Years’ War as a tool to curb Czech patriotism didn’t, of course, go unnoticed. So, while the Poles, for instance, regard the Catholic Church as a cornerstone of their nationhood, quite a few Czechs still perceive it as something that can’t be fully trusted as loyal to their nation — a fact that might also explain why the Czechs in general harbour a rather chilly relationship to religion.

However, it’s usually forgotten that the White Mountain battle, in a wider perspective, actually had some positive effects as well. The Catholic revival after 1648 resulted in a massive construction boom, particularly when it came to ecclesiastical buildings. Some of the most magnificent examples of baroque architecture in Central Europe, such as the St. Nicholas Cathedral at Prague’s Malá Strana or the Klementinum library in Old Town, would probably never have been erected if the Protestant Czechs hadn’t been defeated at White Mountain on that foggy November day in 1620.

And while thousands of Czechs were forced to leave the country, there were thousands of foreignerswho settled in Bohemia and Moravia. Many of them were members of the imperial army and the Catholic League, who received confiscated castles and estates as a reward for participating in the crusade against the Czechs (see: Nobility), which quite understandably helped to ruin foreigners’ image in this country for many centuries to come.

On the other hand, many artists and intellectuals also arrived, especially from Italy, where competition was strong. So paradoxically, what many Czechs still see as one of the biggest tragedies in the nation’s turbulent history was simultaneously a significant contribution to this country’s impressively rich cultural tradition.

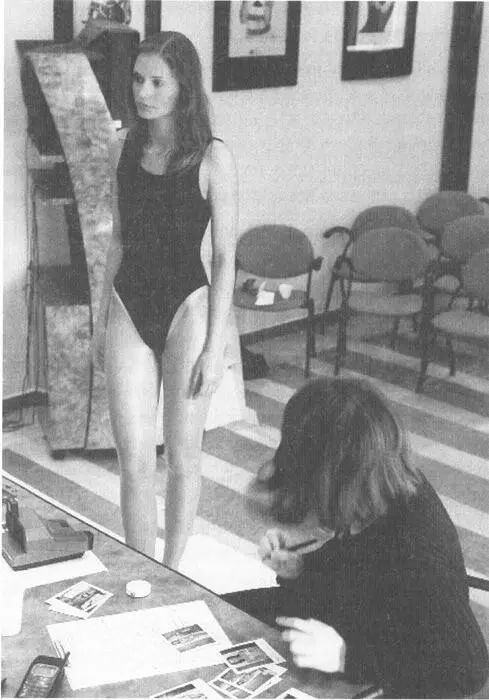

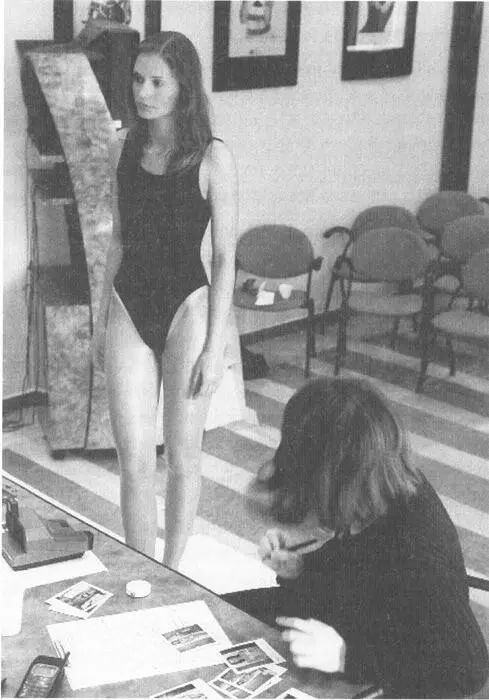

When from time to time some daredevil tries to arrange a beauty contest in a Western European country, he or she can almost take it for granted that the arrangement will provoke wild protests. That’s definitely not the case in the Czech Republic. Beauty contests are neither considered to be politically incorrect nor humiliating to women (see: Feminism). On the contrary, they seem to be an obsession not only for Czech males, but more surprisingly, for the females, too.

Each year there are probably more beauty contests arranged in Bohemiaand Moraviathan in all other European countries combined. The cultural highlight of every Czech region is the election of a local “Miss”. When a new parliament is elected, media immediately pick an unofficial Miss among the fresh members. There is a Miss Deaf, Miss Internet, Miss IQ, Miss Roma, Miss Longhaired, Miss Under-Aged, Miss Czech Railways and even a Missis Mother. In short: picture any profession, company, ethnic minority, village, handicap or whatever, and you can bet your boots that the given group boasts a Miss.

Naturally, the ultimate contest is the election of Miss Czech Republic. The event — broadcast live on TV Novaand with more viewers than any other television program — is preceded by a series of similar contests at the regional level, so at least in theory, Miss Czech Republic can with some credibility claim to be the most beautiful woman in the country.

Photo © Jaroslav Fišer

This is also reflected by the prestige that the title gives its holder. The new Miss, traditionally a 17-year old, scrawny blond who has learnt a poem by heart, is immediately catapulted into the nation’s hottest jet set.

If she plays her cards skillfully, she’ll stay there even after the title is handed over to another beauty.

A safe and frequently-used way to reach this position is to start a relationship with one of the Czech ice hockeystars playing in the NHL (according to some observers, an alliance between those without teeth and those without brains). If that doesn’t work, the Miss title always makes a perfect stepping-stone for a career in business or politics. One Czech Miss even used her title to promote environmental issues.

But how can the Czechs be so out of step with Western Europe, where beauty contests are regarded as a relic from the political Stone Age?

The short answer is that the Czechs, because of their isolation under the communists (see: Ocean), have not until now been confronted with the political correctness that has prevailed in the West for several decades. And since the communists so thoroughly discredited feminism, protests against low-browed beauty contests are not perceived as a defense of women’s rights, but rather as a sullen roar coming from the Bolshevik past. Besides that, more or less every Czech is convinced that no other country on the planet can boast a higher density of beautiful women, so why not take pride in it?

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)