And finally, there is a small group of brave individuals who in the 1950s and 1960s served years in prison and forced labour camps for standing up against the regime, and now, legitimately, demand that their red tormentors should be punished. So far, the former political prisoners’ claims have not met any particular success.

It’s not hard to understand the broad masses’ collective amnesia. Sometime in the beginning of the 1990s, then-Premier (and now, President) Václav Klaus, a gifted populist who has an amazing ability to always formulate things exactly as Pepa Novák — the common Czech — likes to hear them, put it like this: “It’s impossible to drive forward with great speed if you constantly have to look in the mirror.” This is undoubtedly a very handy piece of advice. Especially, a somewhat cynical observer might add, if the things you see in the mirror are not tremendously pretty.

Let’s salt the wounds properly.

The Czechs themselves often say that the communists came to power through a coup ďétat, which implies that it happened against most people’s will. That’s not entirely true. In the elections in 1946, the communists got 38 percent of the votes, which was more than any other party. Consequently, common parliamentarian rules determined that their chairman, Klement Gottwald, became Prime Minister in the “National Front government”, a coalition of six parties.

True enough, in addition to being an alcoholicwith syphilis, “Kléma” was an anti-democrat to the marrow of his bones who received his orders directly from Stalin. But the communists were able to take total control of the government in February 1948 simply because 12 of the non-communist government members resigned as a protest against the Minister of Interior’s scheming, believing that President Edvard Beneš would not accept their resignation.

Well, he did. Silently admitting that Czechoslovakia had become a part of Moscow’s sphere of power, Beneš concluded that the democratic forces didn’t have much of a chance in the long run. Maybe he was right, but the “February Coup” nevertheless smacks of a tactical blunder committed by the non-communist parties. As Gottwald himself later commented with vulgar precision: “They bent forward in front of us, so we simply had to kick them in the ass!” And it’s sad to say, but millions of Czechs were more than eager to help pave the way to disaster.

The Czechs’ enthusiasm for communism didn’t change much after the Bolsheviks came to power, either. When the brave democratic politician Milada Horákováwas sentenced to death in a mock trial in 1950, people were signing petitions in support of her execution. True, the secret police’s repression was strong. Thousands of Czechs fled the country (see: Emigrants), thousands were thrown into jail and labour camps, and almost 180 people were executed.

Some private farmers did actually protest against the forced collectivisation, and there were even signs of open demonstrations when the communists, in 1953, in complete contradiction to what they had promised, carried out a currency reform that rendered most people’s savings worthless.

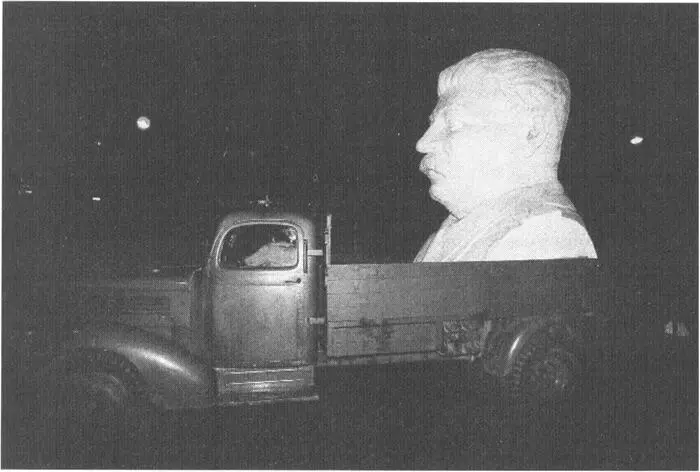

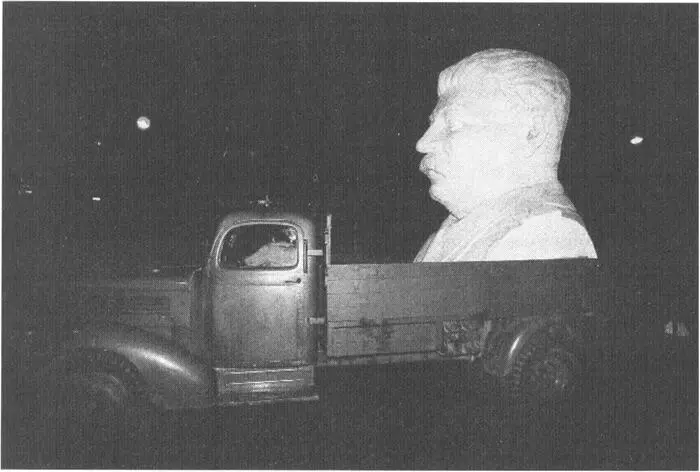

But for the most, the Czechs were content. So, when the Hungarians, in November 1956, were butchered in the streets of Budapest in their desperate uprising against Soviet-style communism, their neighbours in Czechoslovakia were busy buying presents and preparing for Christmas. The Czechs didn’t even hesitate to erect the world’s largest Stalin monument on the Letná Plain overlooking Prague. The atmosphere in totalitarian Czechoslovakia is well illustrated by the fact that the 30-metre-tall, 15,000 tons granite monster was only removed in 1962, nine years after the Soviet tyrant’s death...

Photo © Jaroslav Fišer

But didn’t the Soviet invasion in 1968, which left dozens of civilians dead in the streets, crush far-reaching reforms? Wasn’t the Prague Spring basically an anti-communist uprising? Not really. Alexander Dubček and the other supporters of “Socialism with a human face” definitely wanted to reform Czechoslovakia after 20 years of Stalinism and increasing economic problems. Some of their measures, for instance to remove censorship, represented a giant step towards liberalization, and secured the reformers massive popular support.

However, not even Dubček questioned the Communist Party’s constitutional right to lead society. The Prague Spring reformers also worshipped Marxist-Leninist dogma, and they still believed in the command economy. Even worse, after the 1968 invasion, Alexander Dubček let himself be used as a puppet for the hard-liners by signing laws that were utterly un-democratic. That’s why most Czechs today regard the Prague Spring basically as a battle between two factions of the Communist Party. Or, if you like, as a failed attempt to introduce perestroika and glasnost some 17 years before Gorbachov did.

The 20 years that followed the Soviet invasion are probably the main reason why so many Czechs are loath to look in the historic mirror. In its effort to “normalize” society back to Soviet-style communism, the new secretary general Gustav Husák and his fellow hard-liners kicked some 500,000 members out of the party, and then dissolved every single organization in the country that had shown even the slightest sympathy towards the Prague Spring reforms.

But simultaneously, the neo-Stalinist regime tried their best to secure the common Czech an agreeable standard of living. Their message could be interpreted as follows:

“If you just pretend to respect the fact that we’re running this country, shut your mouth and show up at a pro-regime demonstration from time to time, we will guarantee you a (certainly not too exhausting) job, decent housing, the possibility of buying a Škoda car, a cottage in a beautiful place in the countryside, possibly a vacation at some Black Sea resort, plus, of course, the opportunity to fully exploit all life’s carnal delights (see: Hedonism), starting with inexhaustible quantities of the world’s probably best and definitely cheapest beer.”

A vast majority of the population accepted the deal. Even though the Communist Party was thoroughly cleansed for “liberal” elements after the Prague Spring, it soon had about 1.8 million members, which was, compared to the size of the population, more than in any other East Bloc country, bar Romania (as an expression of their gratitude, the Kremlin made the Czechoslovak officer Vladimír Remek in 1978 the first non-Soviet kosmonaut ever). The human rights movement Charter 77, on the other hand, had about 1,800 signatories, so there were 1,000 Bolsheviks for every singly person who signed the document...

It may sound like a sweeping statement, but it’s tempting to conclude that widespread collaboration with the neo-Stalinist regime, or at least a pragmatic tolerance of it, lasted to the very moment when the economic stagnation became evident to everyone, and it was clear that the Bolsheviks’ days were numbered.

It’s easy, especially for foreignerswho never experienced communism, to poke fun of the Czechs for the way in which they kowtowed to a rotten regime. And yes, after the Velvet Revolutionin 1989 it has undeniably been a bit comic to witness the veritable explosion of anticommunists in the Czech Republic. Even some of the country’s most libertarian politiciansare known to have been either former members of Husák’s neo-Stalinist party, or at least to have flirted intensely with it (see: Lustration).

Yet there are some quite understandable arguments in the Czechs’ defence. In the 1970s, most people really felt that the “normalizors” managed to raise the standard of living. Of course, ruthless exploitation of raw materials, such as coal, and total neglect of ecological measures were the other side of the picture. At the same time, they maintained a hard and repressive line towards any sign of opposition. As a result, the common Czech was markedly better off than the average Pole or Hungarian, while the punishment for openly disobeying the regime was far stronger than those imposed by the regimes in Warsaw or Budapest.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)