A second prototype appeared in 1989, converted from a standard IW. This had a slightly longer barrel and utilized the rear grip from an LSW relocated beneath the muzzle to act as a pistol grip, so at least the user was unlikely to shoot his own fingers off. A third prototype was produced in 1994 with a rather longer barrel, and fitted with the standard LSW (rather than IW) handguard, in the hope that the ridge at the front would prevent the user’s left hand moving forward in front of the muzzle. This relatively low ridge proved inadequate, however, and the weapon was revised once again to mount an LSW rear grip beneath the muzzle as a vertical foregrip, with a prominent stop rib in front of it to prevent the user’s fingers sliding forward. This weapon was eventually adopted in 2003–04 as the L22 Carbine, sometimes known as the ‘Stubby K’. It was issued where space was at a premium, for example to armour crews or attack helicopter pilots. No L22s were actually produced as carbines; the small number in service (around 2,000 weapons) were converted by Heckler & Koch from existing LSWs, made redundant by the adoption of the Minimi LMG.

As might be expected from its short (442mm) barrel, the carbine has a shorter effective range than the rifle, at around 150–200m. It is notably louder than the rifle when fired, and has markedly harsher recoil and a tendency to muzzle climb, especially on automatic.

The L22 Carbine is usually issued to AFV and helicopter crews, but is also used in other situations where a short weapon is advantageous, as here by a boarding team of HMS Somerset . (Cody Images)

An L98A1 Cadet Rifle (below) compared to an L85A1 IW. Note the manual straight-pull bolt, and the absence of a flash hider. This example is not fitted with the usual iron sights mounted on the carrying handle. (Author’s Collection)

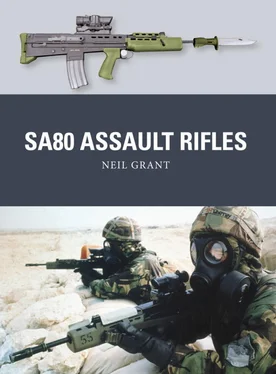

Three iterations of the SA80 carbine. The top weapon is not fitted with any sights – to be usable, it would need either iron sights like the middle weapon, or a SUSAT optical sight like the bottom one. (Author’s Collection)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the MoD dismissed these as ‘teething troubles’ which would be rectified, reminding everyone that the US M16 rifle had experienced similar problems when first issued, before going on to become a very well-regarded weapon. A total of 32 minor modifications were made over the next eight years to fix some of the reported problems. The most notable were a metal shroud that was glued (early) or welded (later) around the magazine catch to prevent it being released accidentally, replacements for parts that proved insufficiently robust and an improved bipod catch. After the Royal Marines in Norway encountered problems with snow balling behind the trigger, preventing it being pulled, the original flat-backed trigger was replaced by a new design with a V-shaped knife edge on the back, allowing it to cut through accumulated snow. Despite these issues, production of the second tranche of weapons was approved; given the amount of time and money already invested, backing out would have been extremely embarrassing for the MoD. The SA80 was about to undergo a much more severe test, however.

The First Gulf War 1990–91

When the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein invaded the small but oil-rich state of Kuwait in 1990, the British government committed 54,000 troops to the US-led coalition to push the Iraqis out again. This deployment – Operation Granby – formed about 10 per cent of the total coalition forces, and the largest national element after that of the United States.

Although sand ingress had previously been identified as a problem with the SA80, little had been done to rectify this, and the British troops encountered problems almost as soon as they arrived in Saudi Arabia to begin training in the desert. As Lieutenant Alistair Watkins of the Grenadier Guards remembers:

We soon discovered irredeemable jamming problems with our SA80 rifle. Taking cover in the sand, and any other movement, had to be done very carefully to avoid getting sand anywhere near it, which obviously wasn’t sensible… We worried all the time about them jamming. Much later, someone buried a captured Iraqi AK-47 in the sand, dug it up then fired and it worked perfectly. Equally, the American M16 rifle was rock solid. (Quoted in McManners 2010: 183)

Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Rogers, commanding The Staffordshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales’s), agreed: ‘If the smallest amount of sand got into our rifle – the SA80 – it jammed. Oiling it, the sand got stuck in the oil, making it worse, and we were to discover further problems with SA80 as the hot weather increased’ (quoted in McManners 2010: 73). Troops used muzzle caps and adhesive tape to seal sand entry-points, kept an empty magazine on the weapon at all times to prevent dirt entering via the magazine well and adopted a routine of cleaning weapons in petrol to remove any oil that might attract sand, then lubricating them liberally immediately before going into action.

British infantry of The Staffordshire Regiment storm a trench system during a live-fire training exercise in Saudi Arabia prior to the 1991 retaking of Kuwait. (© IWM GLF 1425)

When the ground offensive began in January 1991, it was preceded by an intensive aerial bombing campaign which seriously damaged Iraqi ground forces, communication links and infrastructure. Despite some heavy fighting, the coalition forces quickly achieved their objectives, defeating the Iraqi forces encountered and pushing them out of Kuwait before a ceasefire was ordered after only 100 hours of ground combat. The SA80 saw relatively little use due to the short duration of the war itself, and because it largely involved armoured operations in open terrain rather than infantry combat. The troops mostly remained mounted in their vehicles, except for clearing Iraqi positions once they had been overrun. What combat did occur took place at very short ranges (75m or less), and in a number of cases LSW gunners swapped their weapons for IWs issued to the crews of their Warrior IFVs, as the shorter weapon was handier for trench-clearing and able to take a bayonet.

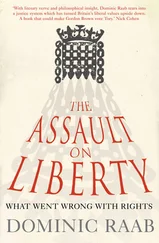

British troops trained in NBC suits for protection from the chemical weapons they feared would be used against them during both Gulf Wars, though thankfully this did not materialize. Respirators significantly degrade marksmanship, particularly in hot conditions when the eyepieces tend to fog. (Cody Images)

In the aftermath of the fighting, the Army’s Land Systems Evaluation Team (LANDSET) reviewed the SA80’s performance during the conflict. Their report pulled few punches:

SA80 did not perform reliably in the sandy conditions of combat and training. Stoppages were frequent despite the considerable and diligent efforts to prevent them… infantrymen did not have CONFIDENCE in their personal weapon. Most expected a stoppage in the first magazine fired. Some platoon commanders considered that casualties would have occurred due to weapon stoppages if the enemy had put up any resistance in the trench and bunker clearing operations. (Quoted in Raw 2003:174)

Читать дальше