Deferring adoption of the LSW gave the Army significant problems. The remaining L4A4 Light Machine Guns could not be kept in service indefinitely, as stocks of spare parts were exhausted; and retaining the GPMG at section level would necessitate significant purchases to replace existing worn-out weapons. It would also mean that infantry sections would need both 5.56mm ammunition for the IWs and 7.62mm ammunition for GPMGs, thus complicating logistics.

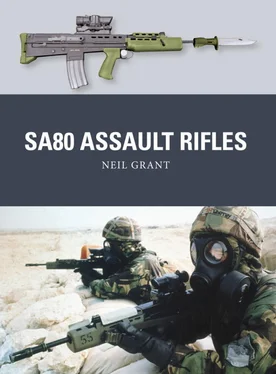

The SA80 was not the only bullpup rifle to be adopted. The Steyr AUG (top) was adopted by the Austrian armed forces in 1978, and has been bought by numerous other armies since then. The same receiver can accept any one of four interchangeable barrels – rifle, carbine, short carbine and a heavy squad automatic barrel with a bipod. It can even be converted to fire from an open bolt in the squad automatic role. The French armed forces adopted the FAMAS (middle) in 1978, replacing both the MAS-49/56 rifle and MAT-49 submachine gun. Both the FAMAS and the AUG are fitted with ambidextrous controls and easily converted at unit level to eject to either side for left- or right-handed use. By contrast, although a small number of left-handed XL70s were produced (bottom) the production SA80 could only be used by right-handed firers. (Author’s Collection)

Going back to the drawing board to design a new LSW that might meet the specifications more closely was not a serious option; it would take several years to develop a new weapon, and there was no guarantee that it would perform any better than the existing LSW. The preferred option was to allow RSAF Enfield a limited amount of time to rectify the problems. Meanwhile, the MoD would define subjective criteria (such as providing ‘effective suppressive fire’) more clearly, and indicate the minimum performance they would accept. Although this would require some compromise, the thinking was that this might be the best outcome for the Army if successful, as it retained the advantages of the original plan.

Finally, the MoD reviewed several foreign weapons that might fulfil the LSW role, including the FN Minimi, the Heckler & Koch HK13 and the Steyr AUG. While adopting a foreign weapon would be politically embarrassing, especially since it would effectively mean writing off the development costs of the British LSW, it provided a fall-back in case RSAF Enfield failed to come up with something that satisfied the revised criteria. As none of the available weapons exactly met the GSR specification – by not having a single-shot capability, not using the same magazine as the IW, or whatever – this would also have required some compromise, as well as losing the advantages associated with commonality.

The revised LSW, with the rearward-folding bipod mounted closer to the muzzle and supported by an outrigger rail, demonstrating the firing position with the left hand on the rear grip below the butt. (Cody Images)

Under the redefined requirements, the LSW had to meet a rather lower standard for providing suppressive fire, while the accuracy requirements were heavily weighted towards single-shot performance, rather than automatic fire where the weapon did less well. Meanwhile, the weapon itself had been modified with a second pistol grip beneath the butt, for better control during automatic fire, and a butt strap to take the weight of the weapon in the prone position. The original LSW prototypes had a bipod mounted just ahead of the handguard. This was changed to a rearward-folding bipod, mounted much closer to the muzzle, giving a more stable platform and improving accuracy; however, this meant extending an outrigger rail out from the handguard to the muzzle to support the bipod, which increased weight.

With these changes, the LSW was finally adopted for service, and a contract for the first 175,000 weapons – now formally known as the L85A1 IW and L86A1 LSW – was awarded in June 1985. The first weapons were handed over in an upbeat and well-publicized ceremony in October 1985.

USE

Expectation versus reality

Acceptance and troop trials

After acceptance, the new weapons went through troop trials in 1986–87 with several units deployed in a variety of environments. It was originally intended that all regular infantry battalions, the Royal Marines and the RAF Regiment would have changed over to SA80 by 1987, and all regular Army forces by 1990. The RAF was to re-equip in 1991. Territorial Army (part-time reservist) units would be re-equipped 1991–93, with priority going to units intended to reinforce the British Army of the Rhine, the forces permanently deployed in West Germany to counter any Soviet invasion during the Cold War. The Royal Navy would be last to re-equip, in 1993.

Despite the earlier ITDU trials, the troop trials revealed a variety of issues with the weapons. Some components proved too flimsy and suffered frequent breakages, while the bipod lock often failed to hold the legs in the closed position. Issue insect repellent melted the plastic furniture, the metal parts rusted quickly in the jungle, sand clogged the mechanism in dusty environments, and the weapons suffered badly from icing in Arctic conditions. The weapons required careful maintenance even in normal conditions, but the cleaning kits issued were flimsy and inadequate. Although left-handed conversion kits were promised during the design phase, none were issued, and the weapons were impossible to use left-handed, as they ejected the hot spent case straight into the firer’s face. Most embarrassingly, the exposed magazine release caught on uniforms and webbing, dumping the magazine out of the rifle at inopportune moments.

SA80 variants

Army Cadet Force and Combined Cadet Force detachments had traditionally been valuable feeder organizations for Army recruitment, as well as promoting community engagement and understanding of the Army. The SLR had been too heavy and had too much recoil to be used by young cadets, however, so .22in (5.6×15mm) bolt-action rifles were used for marksmanship training. The lighter weight and lower recoil of the L85 solved this problem, and a simplified version was developed as the L98A1 Cadet Rifle. This was fitted with dual leaf iron sights, while a straight-pull bolt action replaced the gas system, so the weapon was manually re-cocked for each shot. No flash hider was fitted, so the L98A1 could not mount a bayonet. A plastic oil bottle was initially fitted in clips above the barrel, replacing the gas parts, until it was found that the bottle melted as the barrel heated up. Ultimately, the L98A1 was replaced by the L98A2, essentially a semi-automatic-only version of the L85A2 service rifle. It was intended that cadet weapons would provide a reserve of weapons for the Army, as they could quickly be converted to service weapons, but this proved never to be necessary. The cadet force also had a limited number of standard LSWs, identical to the service version.

Since the bullpup design of the original L85 gave a relatively compact rifle (a length of 785mm versus 840mm for the US M4 Carbine, despite the L85’s barrel being 40 per cent longer), no carbine version was initially planned as part of the SA80 family. An extremely short carbine prototype was created by modifying an XL64 weapon used in the NATO trials around 1984, and converting it to 5.56mm. The barrel terminated immediately in front of the pistol grip, with no grip for the forward hand. The prototype was poorly balanced and difficult to use safely, as the left hand could easily slip forward over the end of the barrel, with obvious and painful consequences for the user.

Читать дальше