It was Tenzin Palmo’s twenty-first birthday, 30 June 1964, when he arrived. ‘It was full moon and we were making preparations for some long-life initiations when the telephone rang. Mrs Bedi answered. “Your best birthday present has just arrived at the bus stop,’ she said. I was so excited and at the same time absolutely terrified. I knew my lama was here,’ she recalled. ‘I ran back to the nunnery to change into my Tibetan dress and to get a kata (the white scarf traditionally given in greeting), but by the time I had got back to the school Khamtrul Rinpoche had already come and gone inside. I nervously ventured after him. He was sitting on a couch with two young lamas, both of them recognized reincarnations. I was so scared I didn’t even look at him. I just stared at the bottom of his robe and his brown shoes. I had no idea if he was young or old, fat or thin.’

Mrs Bedi introduced her, explaining that Tenzin Palmo was connected with the Buddhist Society in England and had recently travelled to India to work with her. ‘I remember thinking that what was she was saying was extremely irrelevant but at the same time being so grateful that she was talking at all,’ Tenzin Palmo continued.

Cutting across the small talk and still not knowing what Khamtrul actually looked like, she blurted out: ’Tell him I want to take Refuge,’ she said, referring to the ceremony when one becomes officially a Buddhist.

‘Oh yes. Of course,’ Khamtrul Rinpoche replied. At that point she looked up.

She saw a tall, large man, about ten years older than herself, with a strong, round face, almost stern in expression and a strange knob on the top of his head. It was similar to that depicted on effigies of the Buddha. ‘The feeling was two things at the same time. One was seeing somebody you knew extremely well whom you haven’t seen for a very long time. A feeling of "Oh, how nice to see you again!” And at the same time it was as though an innermost part of my being had taken form in front of me. As though he’d always been there but now he was outside,’ she explained.

Such is the meeting with a true guru – it happens rarely.

Within hours Tenzin Palmo had also stated she wanted to become a nun, and would he please ordain her. Again Khamtrul Rinpoche said, ‘Yes, of course,’ as though it were only natural. Three weeks later, on 24 July 1964, it was done. ‘It took that long because Khamtrul Rinpoche said he wanted to take me back to his monastery in Banuri to perform the ceremonies there,’ she said, without any trace of irony.

She had been in India only three months, but what seemed from the outside a recklessly hasty decision was to her mind utterly reasonable and completely logical.

’The point was I was searching for perfection. I knew that Tibetan Buddhism not only gave the most flawless description of that state but provided the most clear path to get there. That’s why I became a nun. Because if one was going to follow that path one needed the least distractions possible,’she stated, single-minded as ever.

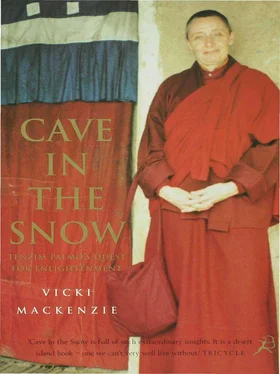

Back home in England, however, Lee was apprehensive. ‘Take a little longer to think about it,’ she wrote to her daughter. But by the time Tenzin Palmo received her letter it was too late. She had already put on the maroon and gold robes and shaved off her long curly hair. She sent a photograph to her mother of her new look, inscribed with these words on the back: ‘You see? I look very healthy. I should have been laughing so then you would know that I am also happy.’ Lee replied, ‘My poor little shorn lamb!’

Her mother was not the only one who was distressed about Tenzin Palmo’s bald pate. On the eve of her ordination, when the hair-cutting ceremony took place, some of the lamas who had grown to appreciate the attractive young woman begged her not to do it. ‘Ask Khamtrul Rinpoche if you don’t need to shave your head,’ one of them implored. ‘I’m not becoming a nun to please men,’ she retorted. ‘When I came out they gawped – they were horrified. But I felt wonderful. I loved it! I felt lighter, unburdened. From that day on I haven’t had to think about my hair at all. I still get it shaved once a month,’ she said.

The day of her ordination is etched indelibly on her mind: ‘I was happy, extraordinarily happy,’ she recalls. All did not go smoothly, however. Following the custom, she had bought some items in Dalhousie to give to Khamtrul Rinpoche as an offering but mysteriously when she went to get them she couldn’t find them. They were completely lost and in fact she never found them again. Going empty-handed to your ordination was, she knew, an awful breach of spiritual etiquette. ‘I felt terrible. When the time came to present my gifts I said to Khamtrul Rinpoche, “I’m sorry, I don’t have anything to give you, but I offer my body, speech and mind.” He laughed. “That’s what I want,” he said.’

Khamtrul Rinpoche then bestowed on her the name Drubgyu Tenzin Palmo, ‘Glorious Lady who Upholds the Doctrine of the Practice Succession’, and in doing so established her as only the second Western woman to become a Tibetan Buddhist nun Freda Bedi being the first. She was to spearhead a movement, for shortly afterwards many women from all over Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand followed in her footsteps, also shaving their heads and donning the robes, helping to formulate the newly emerging Western Buddhism.

Now established as part of Khamtrul Rinpoche’s community, the true meaning of what lay behind their extraordinary first meeting began to be revealed. If Tenzin Palmo had somehow intuitively ‘known’ Khamtrul Rinpoche, he had certainly recognized her. And so had the monks of his monastery. Tenzin Palmo bore a remarkable resemblance to a figure depicted in a cloth painting that hung in the Khampagar monastery in Tibet, which had been in their possession for years. The figure had piercing blue eyes and a distinctive long nose. Furthermore, the figure was obviously someone of spiritual importance because, as others later testified, the monks immediately began to treat Tenzin Palmo with the deference afforded to a tulku, a recognized reincarnation. Khamtrul Rinpoche himself kept her closely by his side, unusual behaviour since he sent most Westerners away, not wanting to attract a following of foreign disciples, unlike other lamas of his time. This special closeness between Khamtrul Rinpoche and Tenzin Palmo was maintained all his life.

What exactly was going on in those unspoken exchanges about previous identities no one with ordinary perception could possibly tell, especially the average Westerner, to whom reincarnation remains largely an enigma. To the Tibetans, however, rebirth was a certainty. We are all born over and over again, they said, in many different forms and situations and to families with whom we have strong karmic connections. In the eyes of the Buddhist, therefore, your mother and father may well have been your parents in a previous life, or maybe even your son, daughter, uncle, cousin, close friend or enemy. The bond had been laid down some time back in ‘beginningless time’and had been cemented in place through countless subsequent relationships. And so it went on, round and round on the wheel of life and death, the mind or consciousness being irrevocably drawn to its next existence by the propensities it had developed within itself.

If rebirth was a given, and quite ordinary, reincarnation was not. Only those who reached the highest level of spiritual development, it was said, could train their mind at the time of death to reincarnate consciously in the precise place and circumstances they wanted. And only reincarnations were sought for and recognized, under the elaborate Tibetan system developed over centuries. These were the tulkus, the rinpoches or Precious Ones, who had forsaken their place in the pure lands in order to fulfil their vow of returning to earth over and over again to release all sentient beings from their suffering.

Читать дальше