At one point during the mushroom ceremony Wasson thought

the visions themselves were about to be transcended, and dark gates reaching upward beyond sight were about to part, and we were to find ourselves in the presence of the Ultimate. We seemed to be flying at the dark gates as a swallow at a dazzling lighthouse, and the gates were to part and admit us. But they did not open, and with a thud we fell back, gasping. {2} 2 2. Wasson, Mushrooms, Russia and History, 295.

Although the visions lasted only a minute or so by watch, Wasson noted that he experienced them as having an aeonic duration, as though he had passed out of the confines of normal time. He was also certain that the visions originated from either the unconscious or from an inherited source of racial memory, concepts borrowed from the work of Carl Jung, with which Wasson was obviously familiar. He readily conceded that the intense visionary episodes arose within him, yet they did not recall anything previously seen with his own eyes. He wondered if maybe the mushroom visions were a subconscious transmutation of things read, seen, and imagined, so much transmuted that they appeared to be new and unfamiliar. Or, mused Wasson, did the mushroom allow one to penetrate some new realm of the psyche?

I assume here that Wasson was referring to something more than a personal unconscious and more like an organized field of intelligence or a transcendental sentience of some sort, interpreted by native shamans as a Great Spirit or God. Wasson failed to elaborate on this matter, preferring to stick to more acceptable ideas, and he ventured no further than Jungian territory in his enthusiastic speculation.

Wasson was also struck by the fact that the dazzling visionary material engendered by the mushroom must reside somewhere within the mind, in a kind of latent state, until the mushroom’s psychoactive constituents stirred them into activity. But how was it possible, he wondered, that we could be carrying around an inventory of wonders deep within us, wonders that the mushroom could unleash so spectacularly? Perhaps, he suggested, some creative faculty of the brain was stimulated by the mushroom and this capacity for creative thought was somehow linked to the perception of the divine.

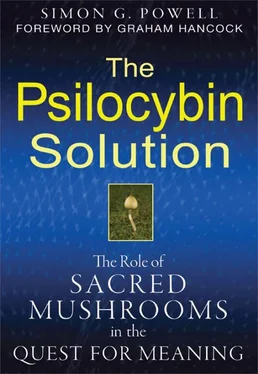

The visionary effects of the mushroom, so clearly related to the experiences of religious mystics, suggested to Wasson that these kinds of fungi might be connected in some significant way to the very origins of the religious impulse, an idea he first introduced in the Life piece and one that he would constantly return to for the rest of his life. Wasson asks us if perhaps the idea of a deity arose after our distant ancestors first consumed psychoactive mushrooms, surely a compelling scenario if we are pushed to explain the origins of religion in natural terms. He was later to help coin the contemporary word entheogen to refer to these sorts of plants and fungi, a word that, although devised to mean “becoming divine within,” is more often considered to mean “generating the divine within.”

Readers of the Life article were also informed as to what the Mexican Indians themselves had to say about the mushroom. The Indians claimed that the fungi “carry you there where God is.” {3} 3 3. Wasson, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom,” 114–17.

Always the mushroom was referred to with awe and reverence. It was not some common drug like alcohol to be taken at the drop of a hat in order to drown one’s sorrows or deaden oneself to reality. On the contrary, native shamans used the fungus for oracular reasons to cure and prophesize. Wasson was intimately familiar with the Indians’ sacred traditions, and he was at pains to portray this cultural phenomenon to his readers in the respectful light it deserved. No Indian ate the mushroom frivolously for excitement; rather, they spoke of their use as “muy delicado,” that is, perilous.

A deeply inspired man, Wasson was not only the first Westerner to document the psilocybin experience; he was also the first to attempt to account for the mysterious effects in reasonable psychological terms, and his tentative speculations remain valid. It is remarkable to think that had he not had such a profoundly spiritual experience, or had his mind not been able to cope with the onslaught of a visionary dialogue, then the Mexican mushroom might well have remained a buried phenomenon to this day. Fortunately for us, this was not so, and the entheogenic mystery is very much alive and “unleashed.” Indeed, given the current world situation in which relentless material consumption is rapidly destroying the biosphere and our value systems are devoid of any vivifying spiritual dimension, the sacred mushroom experience is now more relevant than ever before.

Regarding Wasson’s brave attempts to provide a reasonable explanation for his experiences, I will deal with what is currently known about “the neuropsychological how” of psilocybin in later chapters. For now it is enough to recognize that the mushroom had proved itself to be the psychological analogue of physical fire, its effects able to innervate and enliven the very soul of Homo sapiens .

To simply dismiss Wasson’s visionary encounter as no more than the drug-induced fantasy of a middle-aged man is to miss the point completely. The significance of the entheogenic experience for psychological science alone is enough to warrant our attention since psilocybin is clearly able to galvanize highly constructive systems of thought and emotion into action—that much can be said at the absolute least. Any substance able to evoke an organized flow of symbolic information seemingly issuing from somewhere outside of one’s sense of self, or ego, has got to be worth studying, especially if the experience appears more real than real. And as far as the actual experience of sacred transcendence is concerned, if we are truly interested in such things, if we are truly concerned with perceiving our existence in a way that is beyond the confines of a culturally conditioned secular perspective, then we should surely have cause to investigate the mushroom’s visionary potential. Whereas the most limited explanation for this psychological phenomenon in terms of, say, creative imagination on an unprecedented scale, is still immensely important and fascinating, the more radical and speculative scenarios—which seem compelling when one has personally tasted exhilarating states of mind—offer an even greater and more brilliant conceptual view of reality.

It is here, in the personal impact of the psilocybin experience upon one’s perceptions of reality, that the importance of Wasson’s work resides, for he was able to verbalize his entheogenic experiences in a way that captured their remarkable character. Wasson had shown how sacred realms of experience were not dependent on churches or on the blessings of popes and priests, but could be accessed through the consumption of entheogenic fungi. Wasson had effectively laid such a natural option at the feet of the modern world.

At the end of his seminal account, Wasson discusses the accessibility of the mushroom experience to large numbers people whose psychological disposition might not be in the same league as traditional visionaries like, for example, the poet William Blake. If Wasson was able to briefly become a visionary through eating a simple mushroom, no doubt others would want to follow suit. This inevitable social consequence of his tale was to become manifest in the next decade to a degree that he could never have anticipated, for his news of visionary fungi was instrumental in attracting the West’s interest toward entheogens. As Blake had written, once the doors of perception are opened, the infinite beauty of reality can be discerned. Whether he had planned it or not, Wasson, like his contemporary Aldous Huxley, now had his foot firmly wedged between those perceptual doors.

Читать дальше