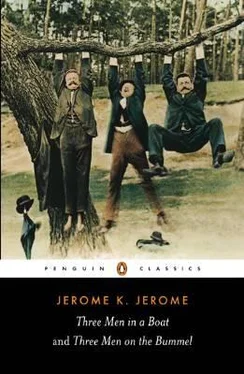

Jerome Jerome - Three Men on the Bummel

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jerome Jerome - Three Men on the Bummel» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Юмористическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Three Men on the Bummel

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Three Men on the Bummel: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Three Men on the Bummel»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Three Men on the Bummel — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Three Men on the Bummel», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

As we explained to the man, the garden or the coal cellar would have been the proper place for the operation; no one but an idiot would have attempted to perform it in a kitchen, and without help.

We gave them hints on etiquette. We told them how to address peers and bishops; also how to eat soup. We instructed shy young men how to acquire easy grace in drawing-rooms. We taught dancing to both sexes by the aid of diagrams. We solved their religious doubts for them, and supplied them with a code of morals that would have done credit to a stained-glass window.

The paper was not a financial success, it was some years before its time, and the consequence was that our staff was limited. My own apartment, I remember, included "Advice to Mothers"-I wrote that with the assistance of my landlady, who, having divorced one husband and buried four children, was, I considered, a reliable authority on all domestic matters; "Hints on Furnishing and Household Decorations-with Designs" a column of "Literary Counsel to Beginners"-I sincerely hope my guidance was of better service to them than it has ever proved to myself; and our weekly article, "Straight Talks to Young Men," signed "Uncle Henry." A kindly, genial old fellow was "Uncle Henry," with wide and varied experience, and a sympathetic attitude towards the rising generation. He had been through trouble himself in his far back youth, and knew most things. Even to this day I read of "Uncle Henry's" advice, and, though I say it who should not, it still seems to me good, sound advice. I often think that had I followed "Uncle Henry's" counsel closer I would have been wiser, made fewer mistakes, felt better satisfied with myself than is now the case.

A quiet, weary little woman, who lived in a bed-sitting room off the Tottenham Court Road, and who had a husband in a lunatic asylum, did our "Cooking Column," "Hints on Education"-we were full of hints,-and a page and a half of "Fashionable Intelligence," written in the pertly personal style which even yet has not altogether disappeared, so I am informed, from modern journalism: "I must tell you about the DIVINE frock I wore at 'Glorious Goodwood' last week. Prince C.-but there, I really must not repeat all the things the silly fellow says; he is TOO foolish— —and the DEAR Countess, I fancy, was just the WEEISH bit jealous"— and so on.

Poor little woman! I see her now in the shabby grey alpaca, with the inkstains on it. Perhaps a day at "Glorious Goodwood," or anywhere else in the fresh air, might have put some colour into her cheeks.

Our proprietor-one of the most unashamedly ignorant men I ever met-I remember his gravely informing a correspondent once that Ben Jonson had written Rabelais to pay for his mother's funeral, and only laughing good-naturedly when his mistakes were pointed out to him-wrote with the aid of a cheap encyclopedia the pages devoted to "General Information," and did them on the whole remarkably well; while our office boy, with an excellent pair of scissors for his assistant, was responsible for our supply of "Wit and Humour."

It was hard work, and the pay was poor, what sustained us was the consciousness that we were instructing and improving our fellow men and women. Of all games in the world, the one most universally and eternally popular is the game of school. You collect six children, and put them on a doorstep, while you walk up and down with the book and cane. We play it when babies, we play it when boys and girls, we play it when men and women, we play it as, lean and slippered, we totter towards the grave. It never palls upon, it never wearies us. Only one thing mars it: the tendency of one and all of the other six children to clamour for their turn with the book and the cane. The reason, I am sure, that journalism is so popular a calling, in spite of its many drawbacks, is this: each journalist feels he is the boy walking up and down with the cane. The Government, the Classes, and the Masses, Society, Art, and Literature, are the other children sitting on the doorstep. He instructs and improves them.

But I digress. It was to excuse my present permanent disinclination to be the vehicle of useful information that I recalled these matters. Let us now return.

Somebody, signing himself "Balloonist," had written to ask concerning the manufacture of hydrogen gas. It is an easy thing to manufacture-at least, so I gathered after reading up the subject at the British Museum; yet I did warn "Balloonist," whoever he might be, to take all necessary precaution against accident. What more could I have done? Ten days afterwards a florid-faced lady called at the office, leading by the hand what, she explained, was her son, aged twelve. The boy's face was unimpressive to a degree positively remarkable. His mother pushed him forward and took off his hat, and then I perceived the reason for this. He had no eyebrows whatever, and of his hair nothing remained but a scrubby dust, giving to his head the appearance of a hard-boiled egg, skinned and sprinkled with black pepper.

"That was a handsome lad this time last week, with naturally curly hair," remarked the lady. She spoke with a rising inflection, suggestive of the beginning of things.

"What has happened to him?" asked our chief.

"This is what's happened to him," retorted the lady. She drew from her muff a copy of our last week's issue, with my article on hydrogen gas scored in pencil, and flung it before his eyes. Our chief took it and read it through.

"He was 'Balloonist'?" queried the chief.

"He was 'Balloonist,'" admitted the lady, "the poor innocent child, and now look at him!"

"Maybe it'll grow again," suggested our chief.

"Maybe it will," retorted the lady, her key continuing to rise, "and maybe it won't. What I want to know is what you are going to do for him."

Our chief suggested a hair wash. I thought at first she was going to fly at him; but for the moment she confined herself to words. It appears she was not thinking of a hair wash, but of compensation. She also made observations on the general character of our paper, its utility, its claim to public support, the sense and wisdom of its contributors.

"I really don't see that it is our fault," urged the chief-he was a mild-mannered man; "he asked for information, and he got it."

"Don't you try to be funny about it," said the lady (he had not meant to be funny, I am sure; levity was not his failing) "or you'll get something that YOU haven't asked for. Why, for two pins," said the lady, with a suddenness that sent us both flying like scuttled chickens behind our respective chairs, "I'd come round and make your head like it!" I take it, she meant like the boy's. She also added observations upon our chief's personal appearance, that were distinctly in bad taste. She was not a nice woman by any means.

Myself, I am of opinion that had she brought the action she threatened, she would have had no case; but our chief was a man who had had experience of the law, and his principle was always to avoid it. I have heard him say:

"If a man stopped me in the street and demanded of me my watch, I should refuse to give it to him. If he threatened to take it by force, I feel I should, though not a fighting man, do my best to protect it. If, on the other hand, he should assert his intention of trying to obtain it by means of an action in any court of law, I should take it out of my pocket and hand it to him, and think I had got off cheaply."

He squared the matter with the florid-faced lady for a five-pound note, which must have represented a month's profits on the paper; and she departed, taking her damaged offspring with her. After she was gone, our chief spoke kindly to me. He said:

"Don't think I am blaming you in the least; it is not your fault, it is Fate. Keep to moral advice and criticism-there you are distinctly good; but don't try your hand any more on 'Useful Information.' As I have said, it is not your fault. Your information is correct enough-there is nothing to be said against that; it simply is that you are not lucky with it."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Three Men on the Bummel»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Three Men on the Bummel» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Three Men on the Bummel» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.