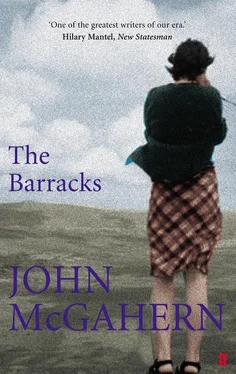

John McGahern - The Barracks

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John McGahern - The Barracks» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Faber & Faber, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Barracks

- Автор:

- Издательство:Faber & Faber

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Barracks: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Barracks»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Barracks — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Barracks», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He no longer slept with her in the big bed with the brass bells and ornaments, but over near the fire-place, on one of the official iron beds that he’d taken out of the storeroom. She’d hear him take off his clothes if she kept silent when he came, the creak of springs, and his sigh of relief as he let the day’s tiredness sink away from him down into the mattress and springs, soon she’d hear the deep even breathing of his sleep. Perhaps one living moment of tension would enter when he’d whisper, “Are you sleepin’ yet. Elizabeth?”

She’d be angry with herself if she spoke: he was too tired, at his turf banks as well as doing the police work, to be kept awake in meaningless talk; but sometimes she had to speak, to try to create some sense of life and movement about her in the night. These words they’d speak or the simple giving and acceptance of a drink or tablet often kept her whole life from breaking into a scream in her mouth.

Such silence and stillness settled over the room and the house, settled over everything except her own feverish mind. With the flickering night light she could follow the boards across the ceiling, then the knots in the boards, dark circles in the waxen varnish; but soon they were lost, the ceiling in as much confusion and emptiness over her eyes as she didn’t know what. She lowered her eyes to the plywood wardrobe, the brass handle shining, and there were some rolls of wallpaper on top that she’d bought and never finished putting up. Reegan’s bed was in the corner over at the fire-place, iron and black, the piping at the top and bottom curved, same as every official bed in so many barracks all over Ireland. She often felt herself go near madness on these nights. She’d want to cry or call: and only she knew she’d be able to renew some sense of life with Reegan when he’d come late she didn’t know how she’d be able to go on. Even when he slept the sound of his breathing kept her mind from worse things, and it was that much contact, her life going out to the dreams of his sleep and the day that had him so dog tired, it didn’t seem so blank as the solid ceiling and wardrobe and the brass ornaments between that caught the moonlight. Then the long wait for morning, always breaking with fierce violence since she could no longer join its noise: dark in the room, Reegan’s deep breathing, and the first cart would rock on the road, faint and far away but growing nearer, rocking past the end of the avenue with a noise of harness and the crunch of small stones under the iron tyres and fading as it went across the bridge and round to the woods or quarry. More carts on the road, rocking now together, men shouting to the horses or each other. A tractor, smooth and humming after the slow harsh motion of the carts; other carts and tractors and a solitary car or van with men travelling to work. The gleam of the brass on the bed grew brighter. She was almost able to see the figures on the face of the alarm clock clearly, see the shape of Reegan rolled in clothes in the bare policeman’s bed. She was hot with thirst and took water from the jug and glass, her feet sticky against the sheets. Outside the morning was clean and cold, men after hot breakfasts were on their way to work. The noises of the morning rose within her to a call of wild excitement. Never had she felt it so when she was rising to let up the blinds in the kitchen and rake out the coals to get their breakfasts, the drag and burden of their lives together was how she’d mostly felt it then, and now it was a wild call to life; life, life and life at any cost.

The light grew clear. She could read the clock, the hands at eight. Perhaps at five or ten or a quarter past the saws would scream and sing in the woods, it might even be later, nothing ran too strictly to time here. The stone-crusher was working in the quarries, the whole morning throbbing with life, calling her out, urging her to rise in passion.

With a bang of doors the children were up, coming into the room to wake Reegan and to wish her good morning. Later, as Reegan put on his clothes, she heard the tongs thud downstairs as they set the fire going.

“Did you sleep well, Elizabeth?” he asked.

“Yes,” she lied, though hard to believe from the look in her eyes.

“That’s powerful, that’s what’ll have you on yer feet soon. The doctor will be here on his way from the dispensary and we’ll ask how about the nurse.”

“That’ll be perfect,” she said. “You’re a little late this morning.”

“Aye — half-eight. Always a rush for this cursed nine. Jesus, people get more like clocks these days and they have to.”

“Will you go on the bog today?”

“You can be sure. I’ll have to see what the men are doin’, though I can’t risk takin’ the day.”

“Who have you?”

He named the workmen as he pulled on his tunic, letting it swing open, and then he was gone for his breakfast.

The fire would be blazing, she remembered. He’d shave before the scullery mirror, the eyes blind with soap and the hands groping for the towel; the kitchen clean and lovely, a white cloth on the table. That’s where she’d love to be now, in the middle of the life of the morning, and not alone and clammy under these bedclothes.

Mullins was barrack orderly, pounding upstairs to the storeroom with his mattress and load of blankets, she saw his shoulders and arms clasped about the grey blankets through the open door and between rungs of the wooden railing. She heard his shovel and tongs at the fire. The outside door opened, the gate at the lavatory clanged, he was going down to the ashpit with his bucket of ashes and pisspot. The iron gate shut, there was some minutes’ delay while he made his morning visit to the lavatory, and then his feet on the gravel and the scraping of his boots at the door.

“Johnny Aitchinson was thrashin’ ashes in Johnny Aitchinson’s ash hole,” repeated itself in her mind after the door had closed, it brought no smile or grimace to her lips — just, “Johnny Aitchinson was thrashin’ ashes in Johnny Aitchinson’s ash hole,” over and over again.

Close to nine he brought some last thing up to the storeroom and then crossed the landing to Elizabeth’s room. Whoever was b.o. came each morning to see her.

“All’s finished and ready to go for the auld breakfast now. I’m just lookin’ in to see how you are,” he stated.

“You’re always very good, John,” she said.

“Not a bit trouble in the world, for nothin’ at all,” he said, put ill at ease by the touch of praise or courtesy; it made him overflow with the feeling that he should somehow be better than he was. She saw the effect of her slight politeness, and wished she’d been silent, it wasn’t true courtesy if it made Mullins so uneasy, only a silly, affected fashion of manners.

“What kind of night had you?” he asked.

“I slept all right,” she said, she must try to divert him away.

“You’re lookin’ better than ever and there’s a powerful feel of the summer comin’ and it’d damned near bring a dead man to life, never mind some one foxin’, like you.”

He’d never accuse her of foxing if it wasn’t blatantly untrue: they must have very little real hope that she’d recover, she thought. She must try to divert him quickly.

“Was there rain, was there rain last night?” she asked. “I couldn’t hear your boots on the ground this mornin’.”

“We can’t make many moves anownt of you, can we?” he bantered. “There was showers, still clouds in the sky, the ground’s as soft as putty. Believe me, you’re not missin’ much not to be out in this weather.”

He was returning to her sickness, though she’d easily fence him away now.

“How is the potato settin’?” she asked.

He began to tell her, the hands of the clock were close to nine: the other policeman arrived below, soon he had to leave her.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Barracks»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Barracks» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Barracks» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.