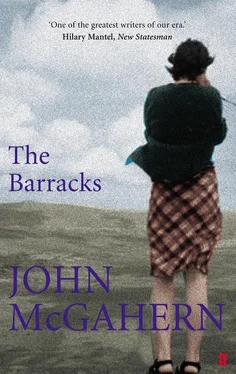

John McGahern - The Barracks

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John McGahern - The Barracks» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Faber & Faber, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Barracks

- Автор:

- Издательство:Faber & Faber

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Barracks: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Barracks»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Barracks — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Barracks», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Casey hated manual work. It was as much as his wife could do to get him to mow the lawn and keep the weeds out of the gravel and dig the beds for the roses she put down so as not to be shamed by the school-teacher who had the next rooms. Not having children to feed he wasn’t forced to take part in this burst of spring industry; he still brought his cushion down with him on b.o. days, kept his gloves on when he wheeled or rode the bicycle, read newspapers and listened to the end of the season’s soccer and the boxing matches and Sports Stadium on Friday nights; and he fenced, “It’s a bloomin’ bad country that can’t afford one gentleman!” when Mullins or more seldom Brennan chaffed.

This was the time when poor Brennan’s best-in-Ireland act started up for the year in real earnest and it went on obliviously till the crops were lifted in October. “Ten ridges, twenty-nine yards long, meself and the lads put down yesterday. Not a better day’s work was done in Ireland,” he’d boast at roll-call, while the others winked and smiled.

Reegan was happy too in this spring, the frustrations and poisons of his life flowing into the clay he worked.

It was good to be ravenously hungry in these late March and April evenings with the smell of frying coming from the kitchen! Would it be the usual eggs and bacon, or might they have thought of getting the luxury of fresh liver or herrings, if the vans brought some to the shops? It was such satisfaction to drag his feet through the gate and look back as he shut it at an amount of black clay stirred, so many ridges shaped and planted; his body was tired and suffused with warmth, the hot blood running against the frost, and there was no one to tell him the work wasn’t done fully right, they were his own ridges, he had made them for himself. And these evenings could be so peaceful when the sawing and stone-crushing stopped and the bikes and the carts and the tractors had gone home. The last of the sun was in the fir tops, the lake a still mirror of light, so close to nightfall that the birds had taken their positions in the branches, only an angry squawking now and again announcing that the unsatisfied ones were trying to move.

He’d wash the dried sweat away inside in front of the scullery mirror and change into fresh clothes before he sat to eat in the lamplight, he’d laugh and make fun with the children and feel the rich communion of being at peace with everything in the world. Never did he get this satisfaction out of pushing a pen through reports or patrolling roads or giving evidence on a court day.

All his people had farmed small holdings or gone to America and if he had followed in their feet he’d have spent his life with spade and shovel on the farm he had grown up on or he’d have left it to his brother and gone out to an uncle in Boston. But he’d been born into a generation wild with ideals: they’d free Ireland, they’d be a nation once again: he was fighting with a flying column in the hills when he was little more than a boy, he donned the uniform of the Garda Siochana and swore to preserve the peace of The Irish Free State when it was declared in 1920, getting petty promotion immediately because he’d won officer’s rank in the fighting, but there he stayed — to watch the Civil War and the years that followed in silent disgust, remaining on because he saw nothing else worth doing. Marriage and children had tethered him in this village, and the children remembered the bitterness of his laugh the day he threw them his medal with the coloured ribbon for their play. He was obeying officers younger than himself, he who had been in charge of ambushes before he was twenty.

That movement in his youth had changed his life. He didn’t know where he might be now or how he might be making a living but for those years, but he felt he could not have fared much worse, no matter what other way it had turned out. But he’d change it yet, he thought passionately. All he wanted was money. If he had enough money he could kick the job into their teeth and go. He’d almost enough scraped together for that as it was but now Elizabeth was ill. He should have gone while he was still single; but he’d not give up — he’d clear out to blazes yet, every year he had made money out of turf and this year he rented more turf banks than ever, starting to strip them the day after he had the potatoes and early cabbage planted. He’d go free yet out into some life of his own: or he’d learn why. He was growing old and he had never been his own boss.

That week-end he brought Elizabeth home. They had taken the biopsy of the breast and sent it to Dublin for analysis. The final diagnoses had come back: she had cancer.

As the next-of-kin Reegan saw the surgeon the Saturday he took her home. He was told she’d have to go to Dublin to have the operation: she’d be let home for only a few days, until such time as a bed was ready, the only reason she was being allowed out at all was that she had pleaded to be let spend the spare days she had between the hospitals in her home.

He wouldn’t say what her chances were — she had definitely a slight chance. If the operation proved successful she might live for ten or even more years. If it wasn’t — a year, two years, he didn’t care to say, he had only taken the biopsy, he was forwarding all his particulars to the Dublin surgeon. He could assure Reegan that she would be in the best hands in the country.

The formality of it was terrifying, the man’s hand-tailored grey suit and greying hair, the formal kindness of his voice. A thousand times easier to lie in a ditch with a rifle and watch down the road at the lorries coming: you had the heat of some purpose, a job to do, and to some extent your life was in your own hands: but this, this.… It was too horrifying, a man or woman no more than a caged rat being given over to scientific experiment. He thought the interview would never be over. He wanted to forget, forget, forget. This wasn’t life or it was all a hell of a flop. It was no use doing anything: it’d be better to take a gun and blow your brains out there and then, but at least Elizabeth was waiting smiling for him, and he couldn’t get her quickly enough away and home.

The five days she was there proved too many. She had to follow instructions, take medicines, stay in bed late, do none of the tasks that had become her life in the house. She was living and sitting there and it was going on without her. The policemen’s wives were constantly in. She had no life whatever then, just chit and chat, skidding along this social surface. She knew she must have cancer. Moments, when she’d suddenly grow conscious that she must be only sitting here and waiting, she’d be seized with terror that it would all end like this, a mere interruption of these banalities and nothing more.

The nights were worse, when she was awake with Reegan and could discuss nothing. Oh, if she could only discuss the operation she was about to face and discover what they both felt! And if they got that far together they might be able to go back to the beginning and unravel something out. There never had been even any real discussion, not to speak of understanding, and while each of them alone was nothing there might be no knowing what both of them might find together. No, she could not even begin when they were awake, silence lay between them like a knife; and he was slaving at the turf-banks these days as well as doing his police work, and was mostly asleep, no sound but some aboriginal muttering rising now and then to his lips, the same that would rise to hers out of the black mysteries of her own sleep.

So it continued till she went, they did not even make simple sexual contact because his hands would come against the bandages. Few were waiting at the town station that morning she went. A cold wind blew down the tracks but the little red-brick building, old and rather pretty, had last year’s holiday posters and narcissi and daffodils tossing between the bare rods of the fuchsias in the beds.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Barracks»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Barracks» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Barracks» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.