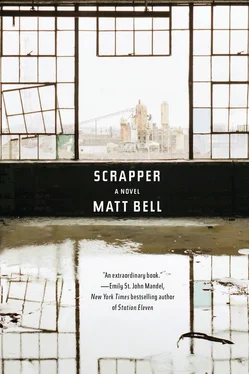

Matt Bell - Scrapper

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Matt Bell - Scrapper» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Soho Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Scrapper

- Автор:

- Издательство:Soho Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Scrapper: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Scrapper»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Scrapper

Scrapper — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Scrapper», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It seemed improbable but he was still growing. He looked taller too but taller was impossible. In the bed he took up more of the space, the covers, the air in the room. He thought often about buying a bigger bed or else another one. In the mirror he often saw he wasn’t as big as he imagined but he was big enough. This was how you stretched the limits of your frame, how you pushed how much muscle you could pack onto these bones, how you learned how much more could fit inside the shell, more again once the human was mostly gone.

When he didn’t know what else to do he plucked her from her wheelchair and carried her around the apartment, being careful not to strike her head against lamps or doorframes or walls. When the weather was better he would take her for walks outside, carrying her up and down the sidewalk, going farther every day. When she started to burn from the sun he smeared her face and neck and hands with sunscreen, found her sunglasses so the light wouldn’t hurt her eyes.

Despite his protests to the doctors she wasn’t exactly the same person she had been before, not the girl with the limp. That person never would have let him carry her, never wanted anyone’s help. But what choice remained. She made noises he interpreted as agreement or disapproval but mostly he was guessing.

At last a whistle blew. The referees separated the fighters, securing them for an agreed-upon number of minutes, the penalty box the punishment for bad behavior, the power play the reward for someone else’s. Every game a microcosm of a longer one. Kelly thought he would wait a long time for his punishment, had already decided he would not fight it when it came. In the meantime, he would be with the girl, sharing her life. It was what he had told himself he wanted, even if he’d never said he wanted it like this.

At intermission, he saw the group of boys before he saw Daniel emerge from their number, walking with the others in their blazers and khakis, shirts and ties. Coming up the stairs and then past, into the concourse, laughing and talking with his friends. Daniel inches taller, his face leaner, a teenager at last.

Kelly knew he should let Daniel pass without acknowledging him but he didn’t think he could help calling out. He couldn’t leave her behind so he backed her away from the railing, pushed her out into the concourse where the boy would see them.

When the boy passed Kelly said Daniel but the boy didn’t hear or if he heard he didn’t turn. And for a moment Kelly saw not the boy passing but the brother, saw how Daniel was growing to look like the brother even though they were not blood.

The boys moved as a unit through the crowd, followed one another into breaches in the confusion, then clumped back up in open spaces. They were moving faster than Kelly could, loudly weighing options for food, souvenirs, talking about the game, the chances for the next period. They cheered for the home team, applied all their boyish arcana, the percentages and statistics and strongly held opinions gleaned from televisions and fathers.

He thought he wanted something else from the boy but what. He couldn’t want thanks and hope to get it. He couldn’t want a relationship with the boy because those days were done. He had been brought into the boy’s life to do something for the boy that the boy couldn’t have done himself and now the deed was done. Now he only needed the boy to see him. He needed the boy to look up at him and see this new body, the spent man within, maybe changing again. But what he wanted to believe had changed him most was not what he had done in the low room but what he had done in the first basement, where he rescued the boy. That despite what happened next it was from the first the salvor he’d wanted to follow.

What he wanted to ask was if the boy was at least safer than before. If safer was enough to be worth the cost.

The boys moved forward faster, slipped away through the cracks in the movements of the crowd. When Kelly pushed at the crowd most of the crowd moved for him, gave the wheelchair room. Others balked, hesitated, looked too long at her, at him, their new bodies, her loose limbs, his logoed t-shirt tight, how the team’s wings and wheel stretched taut over his immense muscles. When he couldn’t maneuver the chair forward through the crush he picked her up into his arms, left the chair where it was. Her body was so soft, limp against his chest, she was lighter and he was stronger. She started to make some noise and this time there was no ambiguity whether she approved or didn’t approve.

The boy, he said into her ear, her cheek beside his cheek. I have to see him.

Daniel, he said. I want to see Daniel.

He could pretend her sounds were no or yes, stop or go . He could pretend whatever he wanted. He stepped forward and the crowd parted. Someone asked if she was okay and he kept walking. He was attracting too much attention but what were his options. There would be a man or a woman who would retrieve the wheelchair and push it after them and he needed to find the boy before this person arrived to force him to play his part. The girl was mumbling into his ear, something repeated, a pattern of sounds, a prayer, a speaking in tongues. Other times he’d shushed her but here he wanted it, wanted it all, wanted her to fill his head with her sound so they might share its nonsense together.

No matter how fast Kelly moved, he couldn’t find the boy again, couldn’t spy a single blue-blazered friend. He wanted to be winded, exhausted, but there wasn’t the slightest need to set her down. This was what this body was good for. He kept walking. People were yelling but he could barely hear them. The ringing in his ears was back again, loud as ever, and Daniel had not turned when Kelly said his name. And no matter how long Kelly looked he knew that had been the moment he’d lost the boy forever.

Back home, Kelly lifted the girl’s cradled form, raising and lowering her as if baptizing her in a river of air, until she began to talk in her fastest speech, so she would give him all the noise she had left, all the sounds at once. That night he took her out into the parking lot, onto the sidewalk, carried her as far as he could. A block this first time. Then on another day two blocks. Then one day ten. The neighborhood they lived in had a name he couldn’t remember. He carried her around its streets, walked past her neighbors, said hello if they said it first but did not stop.

Her neighbors were the people who had known her but with him she was going away, becoming someone else. Someone new, someone new as him.

As he got stronger they went farther, past the bounds of her neighborhood, into the first circles of the zone. He knew there were men who carried their crippled children in triathlons and he thought he could outdo them all. He carried her past those abandoned houses, those shuttered buildings, all the shattered glass and bent steel, burnt wood and broken brick. The same few elements everywhere unresolved. They couldn’t walk at night, not because it was dangerous but because every week there were fewer working streetlights.

The farther they walked the fewer people they saw but he didn’t think they walked to be alone. There were dogs in the street, birds overhead. The power lines were electrified but you couldn’t get the power down on the ground. The rare car went by filled with staring faces but there wasn’t any aggression left in him, wasn’t any fear. Fear required hope to live and he believed he’d put his last hope into the earth. One day the rest of the steel and concrete would collapse overtop it. Everywhere they went they went into the painful past. These places where people had lived. Inside some remainder unrecovered. Their old posters of extinct pop stars, assimilated brands. Old uniforms hanging in closets. He knew what men and women had written on the walls, all the countless forms of goodbye. He’d see a pickup truck pass with a bed full of twisted metal and know it was the future being sold, never merely the past carted away. Every address was a reminder how this pasture had been a home. There were good people living in the zone but he no longer hoped to see them. Seeing the possibility of goodness would make it harder to have done what he had done, to have become what he was. He had come to the zone to escape the past. Then he had discovered the past was all the zone was. The city watch had given him its colors but now he was quitting the team. He had done his grim service. He wanted only to be a spectator again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Scrapper»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Scrapper» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Scrapper» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.