Or else not a ticking but a thudding, the wet slop of uneven blood forced through the centermost chamber of his body, a wet clock counting down to calamity.

After the doctor left Kelly opened his locker, found the promised cash waiting for him in an envelope folded into the back pocket of his jeans, the envelope thinner than he expected but the money all there.

Outside in the parking lot Kelly fell asleep behind the wheel of the truck, the engine off, the cab cold. He woke up, turned the key, put the truck in gear. The engine rumbled to life, the dash lit, its dials incomprehensible enough Kelly knew there was more damage. Or else his life had become a dream, because here was the impossibility of numbers and letters in dreams. He was tired but even tired he was strong. He thought something was punched loose and he thought it would let him do anything. There were a certain number of hours of night left and they would have to be enough. It would be over by morning or else it would never end.

HE HAD PRETENDED HE HADN’T built the body for this purpose but here was the powerful body in perfect motion: The target stepped out of his car, turning to lock the car door as the left fist struck his head twice, as the other arm snaked around the head, catching under the chin with the crook of the elbow, the same hand catching the opposite bicep. The right hand gripping the back of the skull, pushing forward. The elbows brought together, a steady pressure, the free hand squeezing the hold shut.

After Kelly let go he had to mind the seconds, work fast against the count. As soon as oxygen returned so would the world, beat by beat: the parking lot outside the apartment complex, the lit rooms above, the television glares and radio bass. He picked the dropped keys off the pavement, opened the trunk of the target’s car, lifted the groggy target inside. The body heavy and already stirring so he had to strike the target again, every movement nervous now, less controlled, until Kelly landed a punch across the side of the face disorienting enough to let him get the target’s hands behind the back, to get the wrists taped. The legs were stronger, took longer spins of the tape. He didn’t want to suffocate the target but he had to cover the mouth too, ran the tape around the head once, twice, trying to keep it below the nose but working fast.

Kelly shut the trunk, got behind the wheel, locked the doors. He checked his phone, considered the time remaining. It was late but there was plenty of night left. Had anyone seen him? Most of the apartments he could see were dark. The rest were lit by televisions, monitors, the eyes inside the apartments pointed anywhere except the windows. If you lived in a place like this maybe you tried not to look at it.

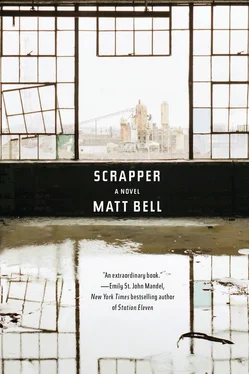

Now the black plant rose again before Kelly, some beginning and middle and end all contained within the plant’s long decline, its still-undemolished structure. Kelly navigated the plant’s expanse of concrete and brick, its streets that would have been strange in the uninhabited deep of the night even without the new snow falling wet and heavy, the slush on the road making the unfamiliar car harder to handle. He parked the car in a brick alley, close to the entrance to the underground. He stepped out into the falling snow, opened the trunk, waited until the target’s eyes found him before displaying the black pistol. He gave orders, explained next steps: How the tape around the ankles would be cut. How the target would get out of the trunk but not run. How running was the biggest mistake the target could make. How they would walk from the car through the open wall of the nearest building. How inside the building there was a broken floor, an aperture beneath which he would find a subtle path down into the basement. How you had to know to look for it. How in the basement there was a hallway that led to a room. How inside the room a metal chair waited. How the target would sit down on the chair.

When the tape was cut the target tried to run but the pistol was there to strike the back of his skull, to prod his stumbling in the right direction: the entrance to the building, the closed door, the collapsed floor, the pitched descent. The gun held the target steady while Kelly worked the padlock installed at the door, then again in the low room, when the target couldn’t find the chair where he’d been ordered to sit, instead reeling around the dark like Kelly had in the ring, the world he’d believed he inhabited having ended so violently it was as if it had never existed.

A sweep of his headlamp revealed the low room as he’d imagined it, untouched since he’d last visited, its square space separated from the world above by a difficult distance. A home for spiders but not much else. Even the rats gone for ages. When he turned off the lamp a stratum of darkness filled the vacuum. He listened to his breathing, listened to the other’s, the crying and the heaving. There was enough tape around the target’s body to make it hard to move, hard to breathe. The crying a nasal wheeze, signaling disbelief in what was happening. Kelly was having trouble too. Both of them together now.

The stale room burst with human activity. Kelly started the generator, let its hum fill the two heavy lights set facing the target. Now there was a darkness where Kelly could retreat, a space beyond the light the target’s vision wouldn’t be able to penetrate. Kelly had forgotten to don the mask but he did so now, the welder’s shield heavy upon his swollen face, burdening his skull. He returned in silhouette, palmed the target’s bound face and pushed it back, applied some pressure. The muscles moving the bones, the teeth and the tongue trapped behind the tape, everything he touched young and healthy, no sign of sickness in the body.

Kelly had waited, watched for borders, thresholds, a birthday. He’d had to make the target a man so he could hurt him like one.

Not a man but a bully, he heard someone say. The face of a bully.

The mouth below his hand was trying to speak too but the words were muffled by the leather of the gloves covering the face, the duct tape beneath. Kelly pictured the head of a horse, then a wasted ape. Something dumbly animal. But who was he picturing. And was it ever the victim who stopped feeling human first.

He used a pair of scissors to open the target’s shirt but he finished the cut with his hands, ripping the fabric to expose the target’s chest, the belly, the arms, the back, the skin swallowed in hurt, heaving with sweat. He was having trouble seeing the target through the harsh glare of the lights but by their glow he knew his own body’s recent unfamiliarity, the largeness of every part of it, the way his straining muscles had stretched over his frame. He was the heaviest he had ever been, possessed a certain enormity he hadn’t imagined possible. Now he thought the deep gravity of the world dragged upon him, the way that gravity grew the lower you sank, the way his hands were not any larger than before but their thickness increased. His thighs squeezed into his pants, feet squeezed into tight boots. His neck a widening trunk for his heavy head, his head lean and strained with veins but weighted with memory begetting action, weighted with the mask and its slim slot of vision. All of it another mistake. As if improving the body were the same as improving the man. As if physical strength made moral right.

When the flesh was exposed he opened one of the duffel bags on the floor, empty except for one last folded item. He shook out the folds, then draped the red robe around the target’s shoulders, pulled the hood up over his head. The target tried to throw off the garment but there were ways to stop his struggling. What was done to the boy couldn’t be undone. Kelly could punish the people who hurt him but it would not rewind the clock. These things happened and somehow he couldn’t help them happening again. He had lived a life meant to avoid the problem and he had slipped once, had sworn off children of his own, but had loved a woman with a child, had loved the child. Then love had not been enough.

Читать дальше