I was sitting in the rooftop bar of the Caravelle Hotel with a dry martini, smoking a cigarette, looking through my contact sheets that I had produced in the small darkroom I had managed to create in a little-used lavatory on the top floor of the SPS building. Back to school — shades of Amberfield and Miss Milburn, the ‘Child Killer’. We had been sending film off to labs in Hong Kong and Tokyo where they were developed, printed and transmitted by satellite to the New York office. But now we could print our own (black and white only) we could send them down the wire, with a short-wave drum printer, so we could be up there with AP and UPI in terms of speed. Even Renata Alabama was grateful. From my point of view it meant I could keep copies of photos I liked — I had my own record and my own little, growing archive. My book was taking shape.

I had a new plan, after my experience at Pluto’s Country Fair. I was going to ignore the field — the combat zones and flashpoints, the search-and-destroy missions — and stick to the bases. My idea was to take pictures of the soldiers, the grunts, off duty. When you saw them shed their carbines and flak jackets, their helmets and ammo packs, you suddenly realised how young these soldiers were — teenagers, college kids. They became youngsters again, not menacing, multi-weaponed warriors, anonymous in their bulky armour.

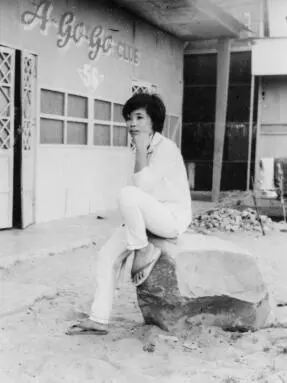

South Vietnam, 1967. From Vietnam, Mon Amour.

And I also started travelling out to the countryside with Truong, taking photographs of the people of this small beautiful country we were visiting as if I were a tourist and not part of the media sideshow of an enormous military machine. I was a war photographer but the book I had in mind would have no war in it.

I looked round at the screech of metal chairs being pushed back against terrazzo tiles and saw the large group of people who had been sitting behind me make their noisy, bibulous exit from the roof terrace. My eyes flicked over the messy detritus of their table — the bottles and the glasses, the ashtrays and the empty cigarette packs, abandoned newspapers — even a book.

I called out: ‘Hey! You’ve forgotten—’ but it was too late, they’d disappeared.

I wandered over to the table and picked up the book. It was French and I felt that shiver of ghostly shock run through me as I read the title and the author’s name.

Absence de marquage by Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau.

Vietnam. The noise of frogs, deafening, in the back garden of the Green Tree coffee shop on Binh Phu Street. Truong introducing me to his family, bowing to me as if I were visiting royalty: Kim, his wife, his two tiny daughters, Hanh and Ngon. A thirty-foot high metal hill of malfunctioning useless air-conditioning machines in a field by Bien Hoa airforce base. The Saigon police in their crisp bleached uniforms — the ‘white mice’. The press escort officer who looked like Montgomery Clift. Endless rain in August. The massive percussion of the B-52 strikes — felt ten miles away, a trembling, an uncontrollable flinching of the facial muscles. The tamarind trees in Tu Do Street. The rich Vietnamese kids in their tennis whites at the Cercle Sportif. Black-toothed women at the Central Market selling US Army gear. ‘We Gotta Get Out of This Place’, a song by the Animals. Motorbikes. Australian troops playing cricket. Beautiful villas on the coast at the foot of the Long Hai Hills — built by the French, decaying fast, empty. Women in conical hats sifting through the waste of US Army rubbish dumps. The smell of joss sticks, perfume and marijuana — Saigon.

I was walking past a bar in Tu Do Street, coming back from my tailor, when I saw a girl sitting outside a shack called the A-Go-Go Club. She was an ordinarily pretty bargirl, her hair teased and lacquered, but there was something about her pensive mood as she sat there dreaming of another life that made me stop and surreptitiously remove my camera. She was wearing white jeans and a white shirt — maybe ready to go on her shift. I snapped her — she never noticed.

‘Shouldn’t you ask permission, first?’

I turned round to see John Oberkamp standing there. He was in jeans and a tight, ultramarine, big-collared shirt.

‘I suppose I should have,’ I said. ‘Do you know her?’

‘She’s my mama-san. Come and meet her.’

Her name was Quyen and she worked in this bar and also at Bien Hoa airbase as a cleaner. She seemed fond of Oberkamp; when she said ‘John, he numba-one man,’ she seemed to mean it. Oberkamp called her ‘Queenie’. We strolled in and ordered a beer. It was mid-afternoon and the place was quiet, the bargirls sitting around in their tiny lurid miniskirts and bikini tops, chatting, smoking, reapplying their make up, waiting for the cocktail-hour rush. Oberkamp told me he finally had accreditation — he was now a recognised stringer for a Melbourne-based newspaper, the Weekly News-Pictorial , and was now spending much of his time with the 1st Australian Task Force at their base, Nui Dat, south-east of Saigon. He came up to the city as often as he could to be with Queenie. He kissed the top of her forehead — ‘My little lady’ — and she hugged herself to him. By coincidence I ran into her again two days later at Bien Hoa where she was polishing the boots of some Air Cavalry gunners. She looked different, hair wild, uncoiffed — a servant, not an object of male fantasy — humble and hard-working. ‘You tell John I love him,’ she said to me. ‘ Beaucoup, beaucoup love.’

Two photos of Queenie. From Vietnam, Mon Amour.

For some reason I can’t bring myself to read Charbonneau’s book. Absence de marquage has been sitting on my bedside table for two weeks, now. I know where this dread comes from: without thinking I read the blurb on the back — it was one of those large-format, pale cream, soft-covered French novels, just lettering on the front, no illustrations. Absence de marquage was the story of a young Free French diplomat — called Yves-Lucien Legrand — in New York during the Second World War, so the blurb informed me, and his doomed love affair with a beautiful English woman, a photographer, Mary Argyll.

I actually felt a squirm of nausea in my throat when I read this and dropped the book as if it were burning hot. Mary = Amory. Argyll = argile , the French for clay. A roman à Clay , then, I said to myself — not amused.

Of course it has to be read, and I have skimmed through it looking for those passages that concerned ‘Mary Argyll’, my alter ego, my doppelgänger. . It’s disturbing to read a fiction when you know all the fact behind it. I’ve been consuming it in small sips, as it were, reading a paragraph here, half a page there, only to realise that Charbonneau was recounting episodes of our time together wholly unaltered in any degree, apart from the names of Yves-Lucien and Mary. Here is Charbonneau describing Mary Argyll after their first night together:

Читать дальше