They continued on what appeared to be a rutted goat track with a median of waist-high weeds that followed on a ridge above the water. Across the Sound of Jura, not quite visible through the rain, the Scottish mainland beckoned with all the conveniences Ray had left behind. His lower back throbbed, his stomach waged war with his nervous system, the pipes — the fucking pipes — screeched at him from the speakers like a state-fair show pig headed to the slaughter, but the little scenery the mist didn’t hide was dreamlike. The motion of the truck allowed his hangover to gain momentum in the pit of his roiling belly.

“How much farther is it?”

“Almost there now, Chappie, and I’ll be done with you and you’ll see what you got your sorry self into. I bet Fuller twenty quid you’ll come crawling back to the hotel before the full moon.”

“The smart money’s on Fuller,” Ray said.

Pitcairn hit a hole as wide around as his tires. “Fuck! I know for a fact that some of these are so deep they’ll take you all the way down to Australia.”

“Stop the car,” Ray said. He hoped, one last time, to lighten the mood and improve relations before they got any worse. Maybe he could establish some kind of rapport with Pitcairn. It would be a mistake to make enemies on an island this small, particularly dangerous ones. “I could go for some grilled shrimp on the barbie.”

“I bet you could, Chappie. I don’t go for all that foreign shite myself. We had some of that Chinese ping-pang ching-chong shite in Glasgow years ago around the time of my boy’s wedding. The old lady wanted to try it. I don’t know why I agreed. ‘Those chinkies will eat dogs,’ I told her. It’s true.”

“It’s hard to imagine that you were ever married.”

“What did you think, that Molly came in the post? That I bought her from Mrs. Bennett? Fucking hell,” he said. The front wheel bounded out of another hole. “They almost caught us that time, Chappie. ‘You never know what they’re feeding you,’ I told the missus. I asked the waiter, ‘Is there dog in here?’ I did, I tell you. She’s dead six years now bless her soul.”

“Molly seems like a very bright girl.”

“Aye, and that’s precisely what worries me, Chappie. She’ll want to get off of Jura one of these days. You’re to stay well clear of her, you understand?”

“You have my word.”

“Your word, huh? And what’s that worth coming from a man who tricks people into buying shite they bloody well can’t afford. Don’t look so surprised. We can read on Jura, Chappie. As soon as the rental agent rang up Mrs. Bennett, she and Mrs. Campbell learned everything we needed to know about you and your sport utility vehicles.”

“I’m glad to hear I was able to provide you with so much entertainment,” he said.

They reached a bend in the track and Barnhill came into view. It was glorious. The size of the house might have justified the rental price. Even painted brilliant white, it did not in any way disrupt the natural splendor of the rolling hills and exposed rock faces, but instead blended in among the curvatures of the ground. It looked cozy.

“I’m glad that you’ll be all the way the fuck up here. What were you thinking?”

It would be an eight-hour walk back to The Stores for any additional supplies.

“I’m thinking I’m home,” Ray said.

A trail led down a little embankment to the house, which sat nestled in a pocket of lower ground between the ridge and a series of hills along the shoreline. The structure had been built on a protrusion into the Sound of Jura, and water surrounded it on three sides; the property included a two-story house with a long garage and a set of stables extending out back to form a U. The hills protected the house from the direct blast of gales from the coast, and a rustic stone wall at the base of the hills appeared to run the entire length of the island. There were no other dwellings in sight. His only neighbors were the countless sheep whose wet wool floated in puffy clouds over the mud. Jura had more of them than the nighttime sky had stars — there had to be hundreds of them clustering in packs large and small.

The front door was on the south side of the property. Ray carried two boxes of supplies down to the stoop before it occurred to him that he didn’t have a key. That was what he had been forgetting. Goddamn it.

Pitcairn’s truck sat idling at the road, the bagpiper wheezing away, and Ray had to march up there and ask him for a ride all the way back to Craighouse. How could he have been so stupid? Did Pitcairn know he had forgotten it? He had brought Ray all the way up here just so he could gloat. He could already hear it: Not so smart now, Chappie, are you? He closed his eyes, took a deep breath. Pitcairn was watching him, and any second now he would lean on the horn.

Ray stood at the door, on the very threshold, but he had to turn around. That had been the story of his life. Out of desperation, he tried the knob — and it turned. The door pushed open and led to a small mudroom. The smell of mildew and garbage punched him in the gut. He put off touring the premises and instead made several trips back up to the truck, where Pitcairn sat smoking a cigarette and reading his newspaper. The boxes of supplies filled the small mudroom and half of the foyer. The whole house stank. After Ray had carried the last of his things inside, he leaned out the door and waved goodbye to Pitcairn, who rolled down his window and whistled. “What do you think you’re doing, Chappie?” he yelled.

Ray walked halfway to the truck. “I’m moving in. Why, what do you think I’m doing?”

“You owe me twenty-five quid for the ride, yesterday and today. Do you imagine that I drove all the way the fuck up here for a joyride?”

“Oh of course,” Ray said. “I owe you twenty-five pounds and you owe me a hundred something for the bar tab last night. We’ll call it an even hundred. So that’s seventy-five pounds you owe me, in fact.”

“Now, Chappie, we talked about that.”

“We talked about that,” Ray said, mimicking Pitcairn’s brogue. “Thanks for the ride — let’s call it even.”

“Even? The next time you need help,” Pitcairn said, rolling up the window, “don’t come crying to me. I’ll expect you tomorrow down at the lounge. ‘Oh I miss my soda pop and telly programs, boo hoo.’ ” He turned the truck around and drove off, kicking up a rainbow of mud. He left a cloud of noxious exhaust behind. The bagpipes died a slow and painful death until, like that, Ray was alone. The wind stirred the trees. The water splashed gently against the rocks down at the water. There existed no human noise whatsoever. Unseen birds welcomed him from the hedges. Wind rippled in waves through the high grasses. The wet peat sucked at the treads of his boots as he fled out of the rain and into George Orwell’s house.

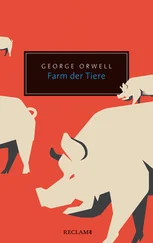

HE PAUSED FOR A moment at the threshold and then removed his boots in the mudroom. Ray was actually in George Orwell’s house. It was difficult to imagine, but Orwell had lived and had written Nineteen Eighty-Four right here. He had paced these very floorboards, watched the sound absorb the rain through these same windows. Going into the sitting room was like stepping back in time. The technological world didn’t exist here yet. It was glorious, but Ray had work to do.

Some kids had broken in — or more likely had let themselves in through the unlocked front door — and thrown a vomitive party in the sitting room. The stench was unbearable. The hardwood floor sparkled with broken wine bottles. Candy wrappers, beer cans, and old newspapers were strewn everywhere. The two fireplaces at either end of the house would provide his only heat, but no amount of peat could warm even the downstairs, where he also found a dining room, kitchen, and water closet. More unlocked doors led to the garage and stables.

Читать дальше