A truck motor rumbled down the road, coughing and sputtering sporadically. I got up and walked out, decided to turn in for the night. But when I walked across the yard, I noticed that it was Papa’s Mazda coming toward the house. I paused, hoping they wouldn’t see me. The truck approached, its headlights throwing wild shadows against the rubber trees. I hoped they’d simply pass me by. They did. But then, just as I stepped onto the front porch, the Mazda stopped. The truck began to back up toward our property. It stopped at the entrance to our driveway.

The driver got out of the car. He started walking toward me, his shadow growing in size, the gravel crunching beneath his feet. At first, I wanted to go inside the house. But then I thought I might say a thing or two to Little Jui. I thought I might give him a piece of my mind. He was alone; there were three of us here. This was our property. If he gave me any trouble, Mama and Papa would come out. I sat down on the porch steps and waited for him.

“What do you want?” I shouted, but he didn’t respond, just kept on walking toward me. “Speak up, motherfucker.”

But, again, no response, only his huffing louder with the closing distance. He was some ten meters away when the moon came out from behind a cloud. By its blue light, I saw that he was not Little Jui at all but that Filipino boy Ramon.

I was afraid now. I’d expected Little Jui — I’d been prepared to confront him once and for all — but I hadn’t expected Ramon. He must’ve sensed my fear and surprise, because he slowed his pace, held his hands before him as though to say he meant me no harm. I stood up. I could smell his sweat now. I could’ve touched his face. He smiled. I turned to go back inside the house, but Ramon reached out and grabbed my hand.

“What do you want?” I whispered, turning to face him, struggling against his grip. His hand felt cold, clammy against my skin. “Go away,” I whispered, and when he smiled at me again, I noticed for the first time his swollen right brow, a messy trail of dried blood branching across his cheek in every direction. He let go of my hand, and though I wanted to turn back to the house, I kept staring into his battered face, mesmerized by the ganglia of blood on his cheek. He said something, but it was in another language — Tagalog, perhaps — and I shook my head to tell him I didn’t understand. He said something again, the same guttural phrase, his voice a dim whisper between us. I shook my head again. “I don’t understand,” I said, and for the first time I saw how helpless he actually was — this foreign boy cast into a foreign land to handle other people’s chickens — and I wondered what had happened tonight to produce those bruises on his face, where he’d been headed in the Mazda before he saw me. He opened his mouth to say something again, but then he took one of my wrists into his hand, as if the gesture might explain what he’d been trying to say. I didn’t resist this time. For a moment, it seemed like Ramon was taking my pulse, his fingers hot against my veins. He reached into the pocket of his jeans. He put something in my hand. He closed my fingers around the object.

“What is this?” I asked, holding up my fist, my fingers hugging the object’s cold, velvety texture. He shrugged. I already knew what it was. I already knew what he’d given me; I didn’t have to open my fingers to see. I didn’t want it. “What is this?” I asked again, but Ramon turned around and started walking back toward the Mazda. I caught up with him. He stopped.

“I don’t want it,” I said. I tried to take one of his hands, return the strange token, but he pulled away and shook his head. He said something to me again in that guttural language. I stared at him. The object felt heavy in my hands, like a warm mushroom, and I realized then that I was squeezing it hard. He reached out, put a hand on my cheek, said something once more. He gestured with his chin toward the Mazda. He pointed toward my house. He put a palm over his heart. I shook my head. “I don’t understand,” I said. “I don’t understand what you want.” He repeated the gestures once more — the Mazda, the house, his heart — and this time, for some reason, I thought I understood him.

He wanted to go home.

“Help,” he said loudly in Thai, and for a moment I stared at him dumbfounded, Papa’s flesh still hot in my fist. “Help,” he said again. “Me.”

He walked to the Mazda. He got in the passenger seat. He sat there for a long time staring at me, waiting. I knew then what I needed to do. I crouched down and started digging a small hole through the gravel driveway with one hand, my fingers still wrapped around Papa’s ear in the other. The ground beneath the gravel was hard, and I felt soil collecting in my fingernails. The hardened topsoil soon gave way to softer mulch, and I clawed at it furiously, grabbing fistfuls of dirt. I thought I might be able to sit there digging in that driveway forever.

I dropped Papa’s ear into that hole and covered it up with clumps of cold gravel. I stood up and walked toward the Mazda. I got in the driver’s seat. I rolled down the window. “Let’s go,” I muttered, popping the truck into gear, and then I was gone.

Thanks are due to many individuals and institutions for their invaluable support and encouragement. This book would not exist without the following believers.

Siriwan Sriboonyapirat. Wannasiri Lapcharoensap. June Glasson. Nancy Lee and Julien Victor Koschmann. Sorachai Buasap. Kawin Punchangthong. Daniel Mrozowski. Jean Henry. Michael Cobb. Hong-an Tran. Cheryl Beredo. Kate Rubin. Charles Baxter, Eileen Pollack, Nancy Reisman, Reginald McKnight, Peter Ho Davies, and Nicholas Delbanco at the University of Michigan creative writing program. My fellow writers in Ann Arbor — Laura Jean Baker, John Bishop, Andrew Cohen, Melodie Edwards, Sara Houghteling, Laura Krughoff, John Lee, Patti Lu, David Morse, Michelle Mounts, and Catherine Zeidler. Lexy Bloom. Fatema Ahmed and Matt Weiland at Granta. Tamara Straus and Michael Ray at Zoetrope: All-Story. Linda Swanson-Davies at Glimmer Train. John Kulka, Natalie Danford, and Francine Prose. The Avery Jules Hopwood Awards Program. The Fred R. Meijer Fellowship in Creative Writing, which provided instrumental funds. The indomitable Amy Williams and the wonderful people at Collins-McCormick. Elisabeth Schmitz, Morgan Entrekin, Dara Hyde, Lauren Wein, Charles Rue Woods, and the incredible staff at Grove/Atlantic, Inc. Thank you all.

This book is also dedicated to the memory of Sucheng Tang — beloved ahmah —who crossed the South China Sea to an uncertain future in Bangkok seventy years ago and who is now, without doubt, enjoying bird’s nest soup in a much better world than the one she inherited.

A GROVE PRESS READING GROUP GUIDE

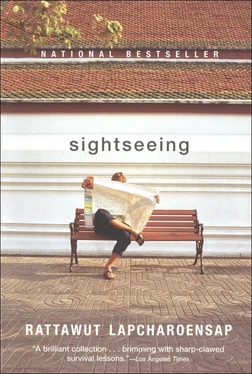

Sightseeing

Rattawut Lapcharoensap

ABOUT THIS GUIDE

We hope that these discussion questions will enhance your reading group’s exploration of Rattawut Lapcharoensap’s Sightseeing. They are meant to stimulate discussion, offer new viewpoints, and enrich your enjoyment of the book.

More reading group guides and additional information, including summaries, author tours, and author sites, for other fine Grove Press titles, may be found on our Web site, www.groveatlantic.com.

SIQHTSEEINQ READERS GUIDE

1. In the story “Farangs,” the narrator is caught between his fascination with Westerners and his elders’ resentment of them. To what do you attribute his interest in these farangs who inevitably disappoint him?

2. Americans are often criticized for being ignorant and indifferent to cultures that exist beyond their own. To what extent do you believe this is true? How is this idea reflected in Lapcharoensap’s stories?

Читать дальше