“I can’t help it.”

“Sugar, you have to. Walk.”

“I just did.”

“Do it again. Get out. Try dancing. Make Doctor Said So keep the babies and go out and have a high time. I’ll set you up, sugar. It’s Italian you want, you want a Frenchman? In a heartbeat, with that hair of yours, I could find you a classy Latin. Why not? Dance a little, sugar. Let him sweat on you. Let him back you into the back of the room.”

“Enough.”

“Enough?” Suzie laughs. “It’s almost nothing.”

“I don’t know why I called,” Bird says.

“You’re drunk, is why. And you’re lonesome. You want someone to say his name to, but you won’t, not even to me.”

“It’s easy for you. You talk to him.”

“I do what I want. That’s me. You’re afraid to want anything. You say his name and the scenery goes to pieces. What I think? You should get in your car and find him. Leave your babies. Go to him. Find out who he still is. He’s in—”

“Cut it out, Suzie Q. Don’t tell me.”

“Why not? He’s in church next door in his underpants. He’s in Ushuaia, look it up, where I saw him last, at the far away tip of the world.”

“You loved him, too, don’t forget.”

“Fool me once,” Suzie says, “many years ago.”

“That worked nicely.”

“Don’t gloat,” Suzie says. “I wanted sunshine.”

“You wanted Mickey. A kitchen sink and a gingham apron. A patch of grass to mow.”

“I’ll let you go now, Bird. I’m going.”

“You wanted to make little red-haired babies!”

“The one time and never again.”

Mickey wouldn’t moveand then he got to moving. Bird went west with him and south, a long way around, and when they came back around to Brooklyn, Mickey looked south again. He wanted out, skip the gray.

We’re soon over, said the note.

He said he was going alone. He went with Suzie.

Suzie spelled him driving south; it was winter. He had bought a car that mostly worked. His radio worked and the windows, all but one. He liked to drive in the heat with the windows down.

He would want a little place, Suzie guessed. Something. A week in a clean soft bed.

But he didn’t. He had his car he thought to sleep in. He found a boat sloshed up from a hurricane he could tack a lean-to on.

“So I’m home,” Suzie called Bird.

It was sleeting. Suzie needed a ride from the bus stop, she had tossed out her winter coat.

“That was useful,” Bird told her, digging. “You didn’t like the sun?”

Sun and windand shadow. A boy on a swing. The grasses golden.

But the days went gray in Denver and cold and they were grounded now, evened out, and Bird’s jaw had begun to stiffen. She couldn’t talk much; she didn’t want to.

The Drive Away clerk went north again — the forecast for old Cheyenne was windy, windy and blue.

They’d go south. South for the heat and sunshine: Nogales, Cuernavaca, La Paz. Eat peyote and sweat with the Mexicans, clear the cobwebs out.

Bird had an aunt in Albuquerque — they could stay a little while with her. She would float them a loan if they asked right and pulled her weeds in the back lot and heated her enchiladas. They’d plant hollyhocks. They would walk her dogs and pick up after them and Bird’s aunt would lend them a car for a day, so Bird could show Mickey around. That’s the room I shared with my sisters, Mickey. There’s the tree house. The ditch where we swam. We had horses. Here’s where my rabbit is buried.

“Hoppy?” Mickey said. “Say you’re kidding.”

“Why?”

“I’m making the rounds with a lunkhead who named her rabbit Hoppy? Not even Hopsalong? Not Floppy?”

He was kidding, but then he wasn’t. They were in a pancake joint and he was loud.

“So what?” Bird asked.

“So what?” Mickey asked. “We nearly married. We made a baby almost. Remember? What did you think to call her?”

“Mickey, stop,” Bird said, “please.”

But he was started.

“You think it doesn’t matter, what you name a thing? Crazy Horse was Curly. When Crazy Horse became Crazy Horse, his father took the name Worm. You think that doesn’t matter?”

He jabbed a waffle with his fork and went at the rim.

“I had an aunt named Alice, my mother’s sister, I could talk to like I never talked to Mother. She had a freckle behind her ear I loved. All over, she had them all over, but that was the one I loved. She liked white food — asparagus, raspberries, cream. It was tenderer, she said, white asparagus. It made your mind clear. White food purified your thoughts. She had no children. Her skin was so white it was blue. She jumped horses. She got her foot hung up in the stirrup one day and was dragged across a field and trampled. Her skull was split. I wanted to see her. I wanted to see what her mind looked like — how clear it was, how true. Auntie Alice. My mother gave me a little pouch of her ashes. I was kid. I wet my finger and dipped it in there. White food. I ate it one flake at a time.”

He dumped sugar on the table he was flicking at Bird.

“We ought to have taken what was left of her, Bird. We kept a tissue, Bird, a piece of the bloody bedsheet. Shame on me. Shame on us. We don’t think right. Everything was there.”

He took a breath but he wasn’t finished. He took her hands in his hands. The day was darkening. It was going to get darker still.

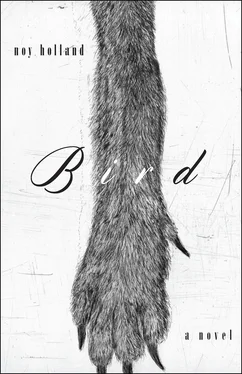

“Bird? I’m the one who named you. Not Faith, not Hope, not Charity. Bird. There’s not a bird I don’t like, not exactly. I like ospreys. I like tiny owls living in holes. I like that cranes find their way by the stars while half their brain is sleeping. Mates for life. The condors that live in the Andes — those monsters mate for life, too. Geese do. Plenty of birds. It’s common. They log thousands of miles, wing to wingtip. They grieve. It takes a heart of rock not to believe it. What I’ve read, I believe is true: you kill a condor and its mate, done in by grief, will plunge to its death from the sky. We don’t believe it because we don’t want to. We want to kill them ourselves with bolas. Lash them to the backs of bulls. We want to climb the trees they are sleeping in and club them on their brainy heads. Call it science. Sport. Gaucho pastime. Darwin’s helpers with geology hammers. When condors sleep, they sleep hard. We call that stupid.

“Cranefly, I could have called you. I could have called you Bean. You think it matters? I called you Bird. I like birds. Birds know too fucking much, it’s spooky. Your Hoppy, no doubt, was dumb. Rabbits are dumb. They die of fright. They scream. Bunny, I could have called you, but I didn’t. I didn’t. People should be named for themselves. You never gave me a name for anything. You call my name like everyone else. Why is that, Bird? You don’t think of me? I’m Mickey like everyone else? I think you’re careless, is what. You’re not thinking. You’re making a mark you can’t see.

“Bird? If I named you for a bird I’d name you Sparrow. Maybe Wren. I thought of Phoebe, a phoebe is faithful, it comes back and goes away. Polyandrous, polyamorous, the loosely colonial — I like them all. I like chickadees, little home-body birds who stick around and sing all winter long. Chickadee. A bird named for its song. I like whippoorwills, sitting alone in the dark coming down. They go quiet. Then they sing the song they were named for in the dewfall and dimming woods. Whip-poor-will . We have to think more. We’re making tracks, Bird, everybody is. There are marks where anyone has been.

“But, Bird? That baby of ours was nothing. We named her to be taken, to be nothing. She was tatters, Bird. A bloody dumpling. Think. Little Caroline, little Caroline. She was nothing. I never even wanted her. I only wanted you.”

Читать дальше