She got dressed and came out of her room. Ah Kwai was still at the vegetable market. Just as she was about to leave and meet Hsueh at the Astor, the phone rang.

The caller was silent for a long while. Therese could hear nothing but crackling and the sound of someone breathing.

“How may I help you?” she asked impatiently.

Silence.

“Who is speaking?” she asked in Shanghainese instead.

“I am Hsueh’s friend.” Therese listened. The woman’s voice sputtered, but Therese couldn’t tell whether it was because the caller was hesitating or whether there was static on the line. The only word she could make out was the word danger .

Then the caller repeated herself, in short bursts punctuated by long silences, still speaking softly: “Don’t go to see Hsueh. They want you dead. You’re in danger.”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“I found a phone number on the back of a photograph in his pocket and knew it had to be yours.” Therese picked up on one solid fact in this confused speech. She knew exactly which photo the woman was talking about.

“Who are you?” she repeated.

“A friend of Hsueh’s,” said the woman in a firmer voice.

“And why would they kill me?” It seemed like an odd question to ask, she thought. She might as well be a stranger wondering: Why would anyone want to kill Therese Irxmayer?

“Now that the deal’s done, you know too much, don’t you see? They don’t have the manpower to kidnap you and hold you somewhere.” That was a bizarre rationale. It made her sound like a plate of leftovers. Save it for tomorrow? Don’t bother, it’ll be too much trouble.

“But what about Hsueh? Will he be all right? Why don’t you tell him?”

“I don’t know where he is, but you know he went to pick up the goods. He’ll come to meet you. They’ll keep him alive because he can still be useful to them.” The voice was cut off abruptly, and there was more static. Before long, the caller hung up gently.

Therese slid down the wall and knelt at the entrance to the living room. The ceramic flooring felt cold on her knees. About fifteen meters of telephone wires curled beside her bare feet. Thinking quickly, she realized she would have to rescue Hsueh. He was probably already on the way to the Astor, and she would barely get there in time. She picked up the phone and rang the jewelry store.

Then she left in a hurry, dashing out of the lobby, crossing Avenue Joffre without even looking both ways.

The Cossacks were ready and waiting in the jewelry store, and the Ford was parked round the back.

They drove north. On Mohawk Road they were held up by a pack of racehorses coming out of the stables, but then the car sped up again. They drove east along the southern bank of Soochow Creek. Therese was riding shotgun. She slipped her hand into her handbag to retrieve a cigarette and quietly chamber a round. The Cossacks already had their guns loaded.

She lit the cigarette and stopped to think. Who was that woman who seemed to know everything? Was she one of Ku’s people? She had never asked Hsueh about his boss or the gang. The French Concession was swarming with gangs, and she couldn’t count the number of criminal organizations to which she had sold guns.

The car was held up again on Garden Bridge. Three empty Japanese military trucks rattled along the bridge, forcing the southbound cars and rickshaws into the northbound lane, and blocking off traffic in both directions. A gang of ragged child beggars swarmed around the waiting cars.

It was nearly ten in the morning, and in the sunlight a foul smell began to rise from Soochow Creek. Therese began fidgeting. She felt something graze the skin on her waist. It was the chain belt, of course — she had quite forgotten about it.

She lit another cigarette, and rolled the window down to get rid of the smoke.

When she looked out, she saw Hsueh sitting in a car whose driver seemed to be deliberately provoking the Japanese soldiers. It was going north ahead of them but had driven onto the right-hand lane, edging brashly between the first two trucks and blocking the southbound cars. Provisions had been unloaded from the trucks, and each had its tarp rolled up behind the hood. A couple of Japanese soldiers stood by the tailgate of one truck, looking impassively at the little French car, as though the neck flaps on their helmets could block out the chaos around them as well as the sun.

She could see movement inside Hsueh’s car. He was leaning back against the headrest, holding a cigarette between two fingers outside the window. She rolled the window down again and pointed him out to her Cossack bodyguards, both of whom had semiautomatic Mauser rifles on their laps. She had to think fast.

They could drive up to Hsueh’s car and gesture wildly at him, but she wouldn’t be able to warn him properly, and knowing Hsueh, he might kick up a fuss. On the other hand, if she waited for them to get out of the car, she could suddenly drive up to them, trusting her Cossacks to keep things under control with their rifles. While the other men were too frightened to move, she could explain things to Hsueh and leave calmly with him.

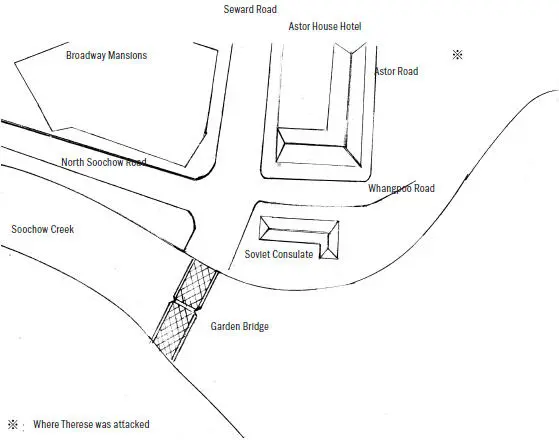

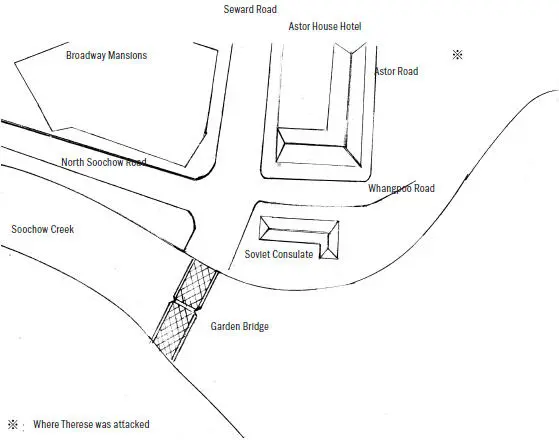

The Astor House Hotel and environs

They started tailing the other car. It was in the right-hand lane and her Ford was in the left, so she could see straight into it. She rolled the window up, knowing the reflected sunlight would prevent her opponent from seeing into her own car. Gazing at Hsueh’s silhouette in the window, she thought what a handsome man he was.

The cars slowly found their way around the roadblock. A few people got out of rickshaws, and the rickshaw men yanked their empty rickshaws onto the sidewalk. One northbound car after another drove slowly up the bridge. The French car merged back onto the left-hand lane, and honked insolently when it passed the last of the Japanese trucks. Therese had her car drive slowly behind them.

The car turned off Paikee Road and past Seward Road toward Whangpoo Road. But Therese directed her driver to turn east on Whangpoo Road instead, and make a U-turn at Astor Road. They could then drive toward the Astor from the other end of Whangpoo Road and cut Hsueh’s car off there. At the corner of Astor Road, she asked the driver to slow down. The sun shone on the pale brown facade of the Broadway Mansions. From inside her own suffocatingly hot car, she could see the other car stopping at the side of the road. Behind it, countless windows glittered.

“Now!” she cried.

As the driver slammed down on the accelerator pedal, the car sped toward the Astor at sixty miles an hour, nearly tipping over as it careened to a halt on the pavement. Hsueh leaped aside and hid in the doorway of the Astor. Two other men had just gotten off, and the car sped toward them, forcing them up against the wall. Hsueh’s driver was speechless.

The Cossacks leaped fearlessly out of the car, and went straight up to the young men. They ignored Hsueh — he was on their side. Brandishing their rifles, they cried in off-key Shanghainese: “No one move!”

No one moved. The young men had their backs to the wall, their eyes wide open. Their hands wandered to their pistols, but they wouldn’t have time to draw.

But the Cossacks had miscalculated badly. Having judged their opponents’ position by their own, it simply hadn’t occurred to them that the driver of the other car might also be armed. Their most dangerous opponent was just outside their field of view. .

Two shots rang out, and both men crumpled onto the porch with the force of the bullets. One was hit in the temple. Another bullet pierced his companion in the left side, just as he was raising the rifle with his left hand, and probably went through his heart. His head thudded onto the white marble porch, exploding like a deranged artist’s convulsive oil painting. (Therese had seen a painting like that in the studio of a White Russian artist who kept up with the latest Parisian trends.) Blood seeped from the man’s crushed skull onto the gray-flecked marble.

Читать дальше