NOW HE SAYS, “I told her to go, hijita.”

Outside, the landscape blurs.

“I told her she couldn’t come home. I didn’t think she’d listen to me — when had she ever listened before? — but she did. She left you.”

It wasn’t the man’s gaze at all, I realize now. It was my own eye that was evil, my own look that was covetous and overlong, my own furious, envious gaze that has made me sick. I wanted my mother and she’d gone to him.

WE HAVE BEGUN our descent through the Manzanos — Cuipas is a meager cluster of buildings in the distance — when we see them, the wild horses. There are two, pulling at the dry grass. My grandfather slows the Mercedes in the middle of the road. The horses are thin. Ribs visible through dusty coats. The Mercedes thrums, diesel coursing, so he turns off the engine. It shudders and goes silent, and then we hear the wind in the grass, weeds scraping against the asphalt edges of the road, and, I’m sure of it, the sound of their mouths as they eat. One of them raises her head, cocks her ears, listening. The light is silver on her velvet muzzle. I’m certain she is aware of us, will raise the alarm, but she dips her head once more and tears at the grass with yellow teeth. I think about a relative long ago losing his horse, calling her name through the mountains, returning to the fort or mission on foot, perhaps never making it, his name lost to history. A third horse emerges from the piñon, swats at the air with her tail.

If I could time my death, I would time it thus: exactly fifteen seconds after my grandfather. I would like to die in my sleep, but I must be certain I outlive him. I will lay my ear against his thin chest, listen to the silence beneath his humped sternum, and then, when I am sure, it will be my turn. Fifteen seconds is good: any longer and I might feel grief. Any longer and I might raise my head to the world opening up before me, wide and calling.

In a moment my grandfather will pat me again, and his hand will stay there, resting on mine. I’ll look down, run a finger along the veins knotted and bruised under his thin brown skin. I wait for his touch. But for now we watch the horses separately, sitting as still as we know how.

FIRST, MY HEARTFELT GRATITUDE TO MY WONDERFUL EDITOR, Jill Bialosky, for her incredible insight and for making this a far better book, and to my amazing agent, Denise Shannon, for being such a generous champion of my work (and for giving me a nudge forward now and again). I still can’t believe my good fortune at getting to work with such brilliance. Thank you also to Bill Rusin, Fred Wiemer, Rebecca Schultz, Steve Colca, Angie Shih, Erin Sinesky Lovett, Francine Kass, Don Rifkin, and to all the other people at Norton who helped guide my book into being.

For time, space, and support, without which I’d probably be in some other field entirely, I am eternally grateful to the Stanford Creative Writing Program, the University of Oregon Writing Program, the MacDowell Colony, the Corporation of Yaddo, Bread Loaf, the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, the James Merrill House, the Elizabeth George Foundation, and the Rona Jaffe Foundation. Thank you for the faith.

I have been blessed with extraordinary teachers who, in the classroom and in the splendid pages of their own books, have challenged me and taught me what a story can do. My deepest gratitude to Tobias Wolff, Elizabeth Tallent, John L’Heureux, and Ehud Havazelet, rigorous and compassionate writers who have pushed me to hold my work and the endeavor to the highest standards. I feel so lucky to have worked closely with them over the years. My thanks also to Adam Johnson, Laurie Lynn Drummond, David Bradley, Peter Ho Davies, and David Wevill, and to the late Charles Terry and Fred Tremallo. For over a decade, Eavan Boland has been a mentor and model for the writer’s role in the world: generous and humane, both in her work and in life.

My gratitude to the members of my workshops at Stanford and the University of Oregon. Thank you also to all my colleagues and students at Stanford and the University of Michigan, who make my job such a pleasure.

So many thanks to Willing Davidson, Carol Edgarian, Tom Jenks, Meakin Armstrong, and Emily Nevins, consummate editors who have made some of these stories worthy of placement in the pages of their journals. Thank you also to the editors who selected some of these stories for inclusion in their anthologies: Laura Furman, Seth Horton, Brett Garcia Myhren, Heidi Pitlor, Elizabeth Strout, and James Thomas.

Particular thanks are due to the dear friends and readers who have left their marks on these stories, whose work inspires me, and whose friendship sustains me: C. J. Álvarez, Molly Antopol, Leslie Barnard, Jason Brown, Harriet Clark, Anna Drexler, Jennifer duBois, Sara Keilholtz, Ryan McIlvain, Kärstin Painter, Brittany Perham, Lara Perkins, Justin Perry, Nina Schloesser, Maggie Shipstead, and Justin Torres. The concept of the painting in “Canute Commands the Tides” was inspired by conversations with the brilliant artist Heather Green, and by her gorgeous series Tide Cycle in particular. Tide Cycle and her other work can be found at heathergreen-art.com. And I am especially grateful to Lydia Conklin, who has been beyond generous with her dazzling critical energies, and whose work and humor and presence bring me such joy.

Finally, mostly, thank you to my family — my parents, Barbra and Jay, my siblings, Gratianne and Emeric, and my grandparents, both Valdez and Quade — for everything, always.

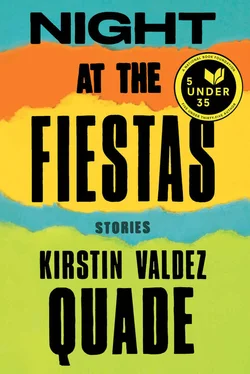

KIRSTIN VALDEZ QUADE HAS RECEIVED A “5 UNDER 35” award from the National Book Foundation in addition to the Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award and the 2013 Narrative Prize. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Narrative, The Best American Short Stories, The O. Henry Prize Stories , and elsewhere. She was a Wallace Stegner Fellow and a Jones Lecturer at Stanford University and is currently the Nicholas Delbanco Visiting Professor at the University of Michigan.