They’d changed the name.

What had once been the Algiers Motel was now the Desert Inn. They’d changed the name but they hadn’t bothered to take down the sign and get rid of that fucking neon palm tree. The place was a blot on the entire police force, on the city itself.

Doyle slowed the Plymouth as he passed. There were a few black guys drinking out of paper bags in the parking lot beyond the swimming pool, out by the annex building. That was the killing floor. That was where cops killed unarmed civilians in cold blood. He was so mesmerized he almost missed “her”—the six-foot Negro with the copper wig and the hot pink mini-skirt and high heels who was hip-swiveling along the sidewalk in front of the motel, dangling a big white purse and checking each car as it passed. Christ, Doyle thought, now they’ve got trannies doing the hooking up here — in broad daylight.

He turned left onto Boston, a boulevard of fading but still-grand mansions. The grandest of them all was off to his right, a three-story palace roosting on a green carpet that was being groomed by black men riding a fleet of little tractors. Country living right here in the heart of the Motor City. Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown records, had paid a million for the place last year, and the understanding around town was that he’d done so to squelch rumors that the company was planning to move to L.A. But Doyle had his doubts, and he wasn’t alone. A million bucks was beer money to a guy like Berry Gordy. Besides, why shouldn’t a thriving record company join the exodus? Did it have an obligation to hang on just because it happened to be owned by a black man? Did Ford Motor Company have a similar obligation just because old Henry made his pots of money here? Nobody squawked when he took his show out to snow-white Dearborn.

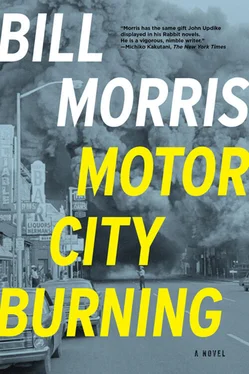

After crossing over the Lodge Freeway, Doyle turned left onto Twelfth Street, where it had all started. The gutted buildings still looked warm to the touch, like the fires had stopped burning nine hours and not nine months ago. Very few of them had been torn down yet, as though someone — insurance companies? the white power structure? — had left them standing as perverse monuments to the madness that had swept this city. Those that had been torn down had usually been replaced by nothing at all, just pebbly, weed-choked lots that glittered more brightly every day with smashed wine and liquor bottles. Ragweed Acres, Doyle called these vistas. Businesses along Twelfth that were untouched or only brushed by the flames had usually been modified — windows filled in with bullet-proof bricks or cinderblocks, a hideous but necessary architectural trend known locally as “Riot Renaissance.”

Driving through his old precinct never failed to depress Doyle. He’d spent three of his seven years in uniform patrolling this neighborhood and he’d grown fond of it. It had never been plush but it was always solid, working-class, and there were still many blocks where people owned their homes, trimmed their hedges and lawns, went to church, belonged to the block association, the U.A.W., the N.A.A.C.P. But they were being nibbled away. Since the riot, whites and many better-off blacks hadn’t been able to get out fast enough.

Now he was passing the shoe repair shop where the first person died during the riot. That case was Doyle’s baptism by fire. The shop was empty now but the red neon shoe was still in the window, unlit, as dead as Krikor Messerlian himself. He was the Armenian immigrant who ran the place, a sweet shriveled old goat who always offered Doyle strong coffee and strong opinions whenever he stopped by to chat. When the neighborhood started to burn last July, Krikor stayed in his shop around the clock, armed only with a fireplace poker and the immigrant’s determination not to back down, not to cede his little patch of the American dream.

When a gang of black kids gathered outside and threatened him through the locked door, Messerlian cursed them and told them to get off his property. Their response was to kick down the door and beat him to death. The police dispatcher used the word “mob,” and when Doyle arrived at the scene Krikor Messerlian was lying inside the shop in a sticky pond of blood alongside a fireplace poker. His face was gone.

Doyle did what Jimmy Robuck had taught him to do at a murder scene: He followed his gut. He told the two uniforms to secure the building and not touch anything while he went knocking on doors in search of a witness because his gut told him they would never have anything on this one without an eyewit. As he turned to go, one of the uniforms, a black rookie, nodded toward a big stucco house across the street and suggested he might want to talk to an elderly lady in a blue dress who lived on the ground floor.

Doyle always did his own door-to-doors because he didn’t trust uniforms with something so important and he’d discovered in his first week on the job that he could get people to tell him things. Mamas, widows, ex-husbands, eyewitnesses, sometimes even the killers themselves — they seemed to want to tell him things. Jimmy Robuck said it was a homicide cop’s greatest gift.

Doyle knocked on a dozen doors before he got to the lady in the stucco house across the street. Her name was Clara Waters and she told Doyle she was on her front porch watering her geraniums when the boys kicked down the door and started beating the old man. She knew the boy who took the pipe, or whatever it was, and used it to smash Mr. Messerlian’s face. She even told Doyle where the boy stayed—“corner apartment in that little two-story brick across from Roosevelt Field.”

The kid was eating a bag of Frito’s and watching “I Love Lucy” when Doyle and Jimmy knocked on his door. He had fresh blood on his sneakers and his fingerprints matched those on the fireplace poker next to Krikor Messerlian’s body. They had the kid locked up, his confession signed and the paperwork on its way upstairs before the Medical Examiner started dismantling Krikor Messerlian’s corpse in the white-tiled autopsy room in the basement.

Yes, this job was all about luck and squealers — and getting people to tell you things.

When Doyle reached Clairmount now he pulled the Plymouth to the curb and shut off the engine. To his right was the building where it had all started. The print shop on the ground floor was still vacant. He wondered if the blind pig upstairs, the United Community League for Civic Action — or was it the United Civic League for Community Action? — was back in business, serving illegal after-hours booze. It wouldn’t have surprised him. Very little surprised him anymore.

The street looked shabby, sadder than ever. People called it “Sin Street” or simply “The Strip,” and during the riot one poet at the Free Press had described this stretch of Twelfth Street as “an ugly neon scar running up the center of a Negro slum.” Doyle didn’t think it was ugly. He thought it was alive. It contained the usual gallery of pawn shops and furniture stores, record shops, soul food restaurants and discount liquor stores, a religious artifacts shop that offered statues of the Virgin Mary, money-drawing oil, skin-whitening ointments. The street was always buzzing. Now he could see the fading words SOUL BROTHER and NEGRO OWNED and AFRO ALL THE WAY spray-painted on certain windows and walls, the black owners’ way of pleading with arsonists and looters to pass them by. Zuroff Furniture Co., once one of the busiest enterprises on the street, was boarded up, a FOR RENT sign out front. It was hard to blame old Abe Zuroff for packing it in. The Jewish merchants had gotten hit especially hard during the riot, and Doyle had often wondered why. Was it simple bad luck, a case of being caught in the wrong place at the wrong time? Or was it something darker, something tribal, a settling of scores for slights, real or imagined, that blacks had been feeling for years in every inner-city in America, Detroit included? Doyle had given up on believing he would ever know the answers to such questions.

Читать дальше