When she returned to her village, however, she was surprised to find that she experienced no sense of going home. She was happy, happy enough, to see her father and sisters again, but her father was still the man who hadn’t followed her to the beast’s castle and done battle for her. Her sisters had married the men they were destined to marry — a brick mason and an ironmonger, sturdily prosaic men who performed their jobs with neither complaint nor ardor, who liked their dinners served promptly at six, and who stumbled home late from the pubs to set about begetting still more children. Beauty’s middle sister had two babies already; the youngest was suckling her first, with a second on the way.

What was most surprising, though, was the fact that Beauty seemed to have developed a reputation while she’d been away.

Although the true story of her time with the beast did not get around, no one believed her father’s version, about her sudden departure for a convent. The villagers agreed that she’d been misbehaving in a remote and foreign place, and that, once some duke or earl had tired of her, or she’d grown too familiar to be the pick of the bawdy house, she was deluded enough to think she could simply come back, as if nothing had happened. Now that Beauty was home again, even the pick of the still-unmarried men (the baker prone to unpredictable spasms of rage, the rabbit-keeper with the squint and the tic) — even those sad specimens — were reluctant about a girl with a past that clearly required a cover-up.

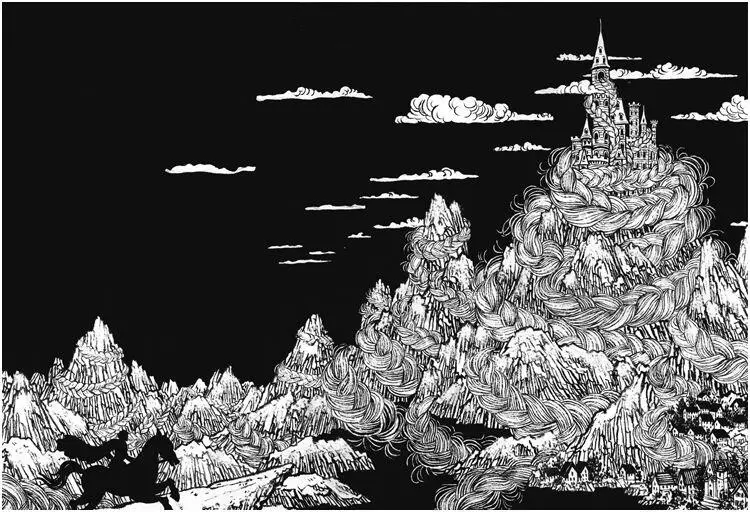

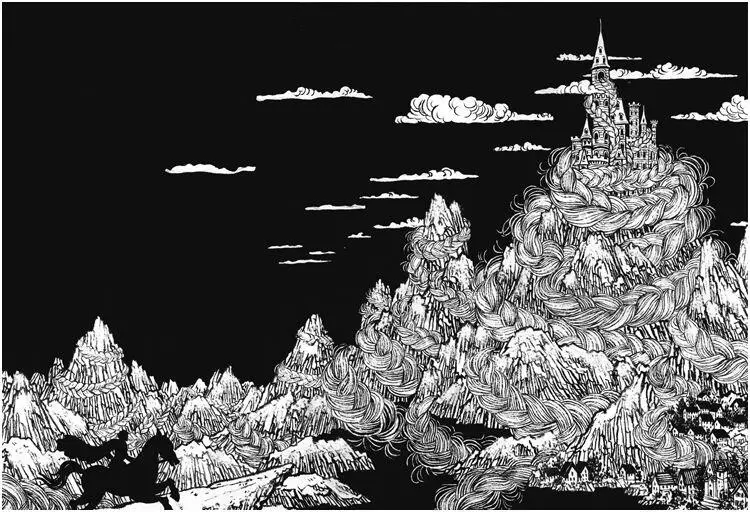

Eventually, late one night (explanations would have been awkward), Beauty slipped away, mounted the horse, and rode back to the beast’s castle. At least she was wanted there. At least she was loved. At least the beast saw no reason for her to be ashamed.

The castle, however, when she arrived, was dark and empty. Its massive doors swung open easily enough, but the candlesticks on the walls did not light themselves as she moved down the hallways. The cherub faces in the molding were merely carved, unliving wood.

She found the beast in the garden, which had turned weedy and rank, its hedges throwing out branches like panicky, irrational thoughts. The fountain, gone dry, was etched all over with hairline cracks.

There, on the paving stones before the arid fountain, lay the beast.

Beauty knelt beside him. Although he was too far gone to speak, she could still see a flicker in his yellow eyes.

She lifted, with effort, one of his paws in her small hands. She told him quietly, as if it were a secret, that she’d realized she loved him only by being parted from him. She wasn’t lying; she wasn’t exactly lying. She did love him, in a way. She pitied him, she pitied herself, she grieved for both of them — souls who seemed to have gotten so easily and accidentally lost.

And if he could be healed, if he might be brought back from death’s brink …

She loved the image of herself turning proudly from the low lot of village men who’d deign to have her; she loved the idea of saying no to the baker and the rabbit-keeper and the filmy-eyed old widower whose once-respectable house was going slant on its foundation, shedding shingles into the town square.

She would be the bride of a beast. She would live in his castle. She would care nothing for the whispers of biddies and gossips.

She said softly, into the beast’s furry ear, which was bigger than a catcher’s mitt, that if he could revive himself, if he could manage to rise again, she’d marry him.

The results were instantaneous.

The beast leapt up with a lion’s fervor. Behind him, the fountain spurted water again.

Beauty stepped back. The beast looked adoringly at her. He looked at her with a thankfulness that was marvelous and, somehow, dreadful to see.

In less than a moment, the beast’s hide split open like a chrysalis. The claws and fangs fell away. The feral reek evaporated.

And here he is.

He’s stunning. He’s sturdy, square-faced, snapping with muscle.

The prince stands among the snarls of shed fur, the claws that litter the paving stones. He looks down in amazement at his restored body. He flexes his human hands, tests the athletic springiness of legs that are no longer taloned haunches.

The spell has been broken. Did Beauty suspect it, all along? She’ll enjoy the idea that she’d intuited it, that she was a girl who could ferret out the workings of enchantment, but she’ll never be sure.

She waits breathlessly, ecstatically, for the newly summoned prince to take her in his arms. But first he has to check his reflection in the water, which is already rippling in the revived fountain.

It’s worked. He’s managed it. He’s seduced a lovely woman into pledging her troth to a soul that’s been concealed — to everyone but her — by disfigurement.

Beauty’s pale bosom heaves with anticipation.

The prince turns slowly from his own reflection, shows her a lascivious, bestial smile; a rapacious and devouring smile. Although his face is impeccably handsome, something about it is not quite right. The eyes remain feral. The mouth seems capable, still, of tearing out the throat of a deer. He could almost be the beast’s younger, handsomer (much handsomer) brother, as if his parents had produced a deformed child and then a beautiful, perfectly proportioned one.

Beauty begins, suddenly, to wonder. Is it possible that the beast-spell was meant, long ago, as protection? Had the prince been locked into a monster’s guise for decipherable reasons?

She backs away. Grinning victoriously, emitting a low growl of triumph, he advances.

After the witch caught on …

after she cut off Rapunzel’s hair …

after the prince fell from the tower onto the thornbush, which pricked out his eyes …

He wandered the world searching for her, astride his horse. He took no one with him other than the horse.

He knocked on a thousand doors. He rode along village streets and down country lanes, calling out her name. Her name was sufficiently strange that the villagers and farmers he passed assumed him to be deranged. It never occurred to them that he might be seeking an actual person.

Some were helpful: There’s a river ahead, watch out for the gully coming up . Some threw stones at him, some flicked switches at his horse’s gaunt flanks.

He didn’t stop. He searched for a year.

Until, finally, he found her …

he found her in the desert shanty to which the witch had banished her …

he found her living alone, with dust devils swirling through the curtains, with flies thicker than the dust …

She knew him the moment she opened the door, though he was all but unrecognizable by then, sallow and torn, his raiment in rags.

And there were those empty black sockets, the size of ravens’ eggs, where his eyes had been.

He said only, “Rapunzel.” A word he’d spoken at a thousand thresholds already, and been a thousand times turned away, either cruelly or kindly, for the destitute and deranged creature he’d become. There is, as he’d learned, a surprisingly fine line between a prince on a quest and an addled, eyeless wanderer who has nothing more useful to offer than that single, incomprehensible word.

He’d come to know the condition of the benighted; he who had, a year earlier, been regal and splendid, broad and brave, climbing hand over hand up a rope of golden hair.

When he stood finally at her doorway, having sensed the presence of a house, having felt his way along its splintery boards until he touched a threshold …

when she reached out to touch his scabbed and bleeding hand, he recognized her fingers a moment before they made contact with his skin, the way a dog knows its master is approaching, while still a block away. He emitted a feral moan, which might have been ecstasy or might have been intolerable pain, as if there existed a sound that could convey both at the same time.

Читать дальше