Michael Cunningham

A Wild Swan: And Other Tales

Most of us are safe. If you’re not a delirious dream the gods are having, if your beauty doesn’t trouble the constellations, nobody’s going to cast a spell on you. No one wants to transform you into a beast, or put you to sleep for a hundred years. The wraith disguised as a pixie isn’t thinking of offering you three wishes, with doom hidden in them like a razor in a cake.

The middling maidens — the ones best seen by candlelight, corseted and rouged — have nothing to worry about. The pudgy, pockmarked heirs apparent, who torment their underlings and need to win at every game, are immune to curse and hex. B-list virgins do not excite the forces of ruination; callow swains don’t infuriate demons and sprites.

Most of us can be counted on to manage our own undoings. Vengeful entities seek only to devastate the rarest, the ones who have somehow been granted not only bower and trumpet but comeliness that startles the birds in the trees, coupled with grace, generosity, and charm so effortless as to seem like ordinary human qualities.

Who wouldn’t want to fuck these people up? Which of us does not understand, in our own less presentable depths, the demons and wizards compelled to persecute human mutations clearly meant, by deities thinking only of their own entertainment, to make almost everyone feel even lonelier and homelier, more awkward, more doubtful and blamed, than we actually are?

If certain manifestations of perfection can be disgraced, or disfigured, or sent to walk the earth in iron shoes, the rest of us will find ourselves living in a less arduous world; a world of more reasonable expectations; a world in which the appellations “beauty” and “potency” can be conferred upon a larger cohort of women and men. A world where praise won’t be accompanied by an implied willingness to overlook a few not-quite qualities, a little bit of less-than.

Please ask yourself. If you could cast a spell on the ludicrously handsome athlete and the lingerie model he loves, or on the wedded movie stars whose combined DNA is likely to produce children of another species entirely … would you? Does their aura of happiness and prosperity, their infinite promise, irritate you, even a little? Does it occasionally make you angry?

If not, blessings on you.

If so, however, there are incantations and ancient songs, there are words to be spoken at midnight, during certain phases of the moon, beside bottomless lakes hidden deep in the woods, or in secret underground chambers, or at any point where three roads meet.

These curses are surprisingly easy to learn.

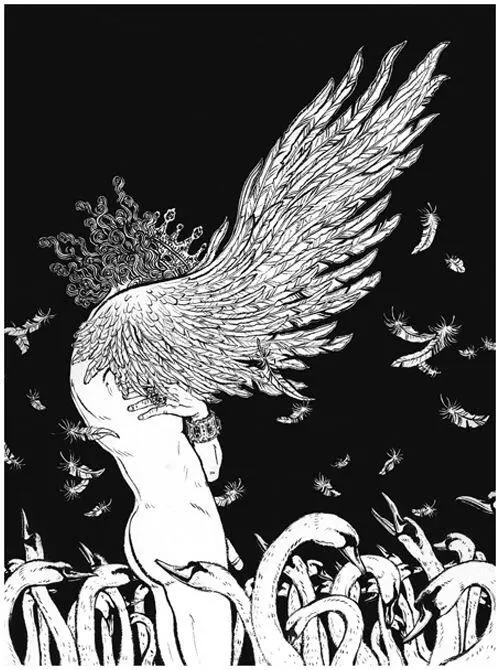

Here in the city lives a prince whose left arm is like any other man’s and whose right arm is a swan’s wing.

He and his eleven brothers were turned into swans by their vituperative stepmother, who had no intention of raising the twelve sons of her husband’s former wife (whose pallid, mortified face stared glassily from portrait after portrait; whose unending pregnancies had dispatched her before her fortieth birthday). Twelve brawling, boastful boys; twelve fragile and rapacious egos; twelve adolescences — all presented to the new queen as routine aspects of her job. Do we blame her? Do we, really?

She turned the boys into swans, and commanded them to fly away.

Problem solved.

She spared the thirteenth child, the youngest, because she was a girl, though the stepmother’s fantasies about shared confidences and daylong shopping trips evaporated quickly enough. Why, after all, would a girl be anything but surly and petulant toward the woman who’d turned her brothers into birds? And so — after a certain patient lenience toward sulking silences, after a number of ball gowns purchased but never worn — the queen gave up. The princess lived in the castle like an impoverished relative, fed and housed, tolerated but not loved.

The twelve swan-princes lived on a rock far out at sea, and were permitted only an annual, daylong return to their kingdom, a visit that was both eagerly anticipated and awkward for the king and his consort. It was hard to exult in a day spent among twelve formerly stalwart and valiant sons who could only, during that single yearly interlude, honk and preen and peck at mites as they flapped around in the castle courtyard. The king did his best at pretending to be glad to see them. The queen was always struck by one of her migraines.

Years passed. And then … At long last …

On one of the swan-princes’ yearly furloughs, their little sister broke the spell, having learned from a beggar woman she met while picking berries in the forest that the only known cure for the swan transformation curse was coats made of nettles.

However. The girl was compelled to knit the coats in secret, because they needed (or so the beggar woman told her) not only to be made of nettles, but of nettles collected from graveyards, after dark. If the princess was caught gathering nettles from among tombstones, past midnight, her stepmother would surely have accused her of witchcraft, and had her burned along with the rest of the garbage. The girl, no fool, knew she couldn’t count on her father, who by then harbored a secret wish (which he acknowledged not even to himself) to be free of all his children.

The princess crept nightly into local graveyards to gather nettles, and spent her days weaving them into coats. It was, as it turned out, a blessing that no one in the castle paid much attention to her.

She had almost finished the twelve coats when the local archbishop (who was not asked why he himself happened to be in a graveyard so late at night) saw her picking nettles, and turned her in. The queen felt confirmed in her suspicions (this being the girl who shared not a single virginal secret, who claimed complete indifference to shoes exquisite enough to be shown in museums). The king, unsurprisingly, acceded, hoping he’d be seen as strong and unsentimental, a true king, a king so devoted to protecting his people from the darker forces that he’d agree to the execution of his own daughter, if it kept his subjects safe, free of curses, unafraid of demonic transformations.

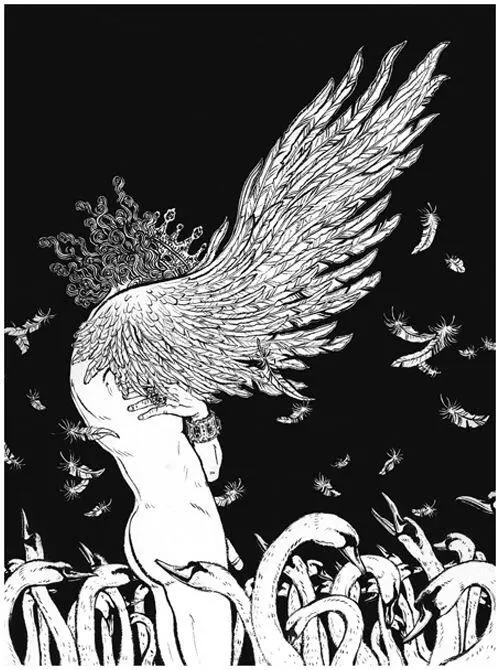

Just as the princess was about to be tied to the stake, however, the swan-brothers descended from the smoky sky, and their sister threw the coats onto them. Suddenly, with a loud crackling sound, amid a flurry of sparkling wind, twelve studly young men, naked under their nettle coats, stood in the courtyard, with only a few stray white feathers wafting around them.

Actually …

… there were eleven fully intact princes and one, the twelfth, restored save for a single detail — his right arm remained a swan’s wing, because his sister, interrupted at her work, had had to leave one coat with a missing sleeve.

It seemed a small-enough price to pay.

Eleven of the young men soon married, had children, joined organizations, gave parties that thrilled everyone, right down to the mice in the walls. Their thwarted stepmother, so raucously outnumbered, so unmotherly, retreated to a convent, which inspired the king to fabricate memories of abiding loyalty to his transfigured sons and helplessness before his harridan of a wife, a version the boys were more than willing to believe.

End of story. “Happily ever after” fell on everyone like a guillotine’s blade.

Almost everyone.

It was difficult for the twelfth brother, the swan-winged one. His father, his uncles and aunts, the various lords and ladies, were not pleased by the reminder of their brush with such sinister elements, or their unskeptical willingness to execute the princess as she worked to save her siblings.

Читать дальше