I pulled the sheet up over my head and let it fall to the floor, crumpled. It was a relief — to pull the sheet from my body, to peel it from me where it had fused to my skin and yellowed, to expose my tingling arms to the air — but somehow it annoyed me to show my face to this strange new girl. She reminded me of B, consuming my face with her eyes, thickening the air with her presence. To see her lounge around in her skin as if it were the only natural thing to do highlighted how unnatural anything was for me now. I decided to call her Anna, which wasn’t so far from my own name. It was palindromic, which seemed to suit someone who was destined to become my mirror. It was short and easy to remember. It was the name I had given to my favorite doll, the one that I asked my mother to throw away after I noticed something overly human about its eyes.

My hair clung to my skin like a bark. “You look exhausted,” Anna said, sitting forward on the cot and looking at me hard from both eyes. “Much more tired than me. I’ll work on getting my face a little bit wearier, but I always tend to sleep well. I think it would be better if you’d work on getting some more rest. The closer we are in body and appearance, the easier it’ll be to merge our life.”

I didn’t say anything.

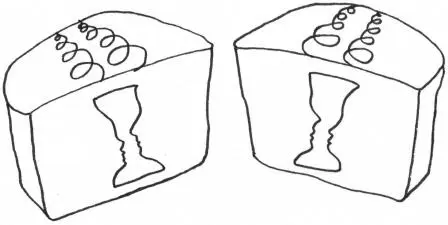

“If we are as One Person, spread out over two bodies,” she said in a pert, authoritative tone, “we’ll halve our load and ghost much earlier.”

“I know,” I said, but I didn’t.

Then from behind me I heard the sound of the curtain being pushed aside, and a dinner tray slid into our space, its contents obscured under a gleaming metal cover. I picked it up and looked out into the corridor to see if another was coming, but there was nobody there.

I turned back to Anna and told her: “There’s only one.”

“Of course there’s only one,” she said. “We share everything now.”

I looked down at the shining tray. I had no idea what it might be. A purer food, probably, or maybe a less pure one if they wanted to test our powers of distinction. I had to remind myself to keep my hopes down, that it might not be food at all — though the thought made my stomach ache with hunger. I took a breath and then I lifted the cover off the tray.

What I found there was a small heap of Kandy Kakes, twelve of them piled on a white plate. They were just as I had pictured them over the last few difficult months: a double squiggle of frosting-flavored icing gracing the dark, hard surface of its chocolate-armored puck. Just as I had pictured — only, if possible, even more beautiful.

I almost couldn’t believe this was really happening. I would grow clearer, thinner, Brighter, a more perfect vessel for my ghost. I felt a great burden lift from me, the burden of worry over what I was, what was becoming of me. With the help of these Kandy Kakes, I would finally become better in the Bright future ahead.

“Why are you crying?” asked Anna, annoyed.

I tried to explain: “I’ve waited so long for these.”

Anna shrugged. “Well,” she said. “Congrats.”

I picked one up and brought it to my mouth. Of all the things I had wanted in my life, these were the only ones left. I felt my body grow hot, then cold, then hot again: I wanted to cram them all whole into my mouth, force them down. I breathed in their scent of hard, waxy chocolate and stale orange. My throat was wet and wide and tender.

Then I bit. It was harder than I liked, the casing exactly as impermeable as the ads boasted. I shifted it toward the back molars, where my jaw was a little stronger, and managed to pierce the chocolate armor, crush it a little, so that the syrupy orange-caramel filling began its seepage into my mouth. The orange goo tingled with sweetness against my tongue.

I looked up and saw Anna watching me.

“It’s delicious,” I said.

She nodded and blinked.

As I took up my second Kake and third Kake and bit down through their Choco Armor, I tried to remember only this moment, this present moment that was continually ending, this moment illuminated by the safety and Brightness of the Church, but I couldn’t help it. Even though I knew it only harmed me, only hindered my progress, I was thinking of my old life, of the way B used to watch me eat. I’d be reading old sections of the Sunday paper while eating a bowl of cereal, and every once in a while I could look up to see her eyes on me. The look in them was something strange. She stared at me like I was doing something new that she wanted to do very badly. She stared at me like I had performed an ugly miracle. She stared at me like she’d be practicing it later, in her room, alone — standing in front of the mirror and chewing exaggeratedly, cowlike, biting at the air.

THAT NIGHT, I WOKE TOa feeling of hunger that verged on pain. I rolled over on my side and clutched my belly in toward my center, as though compressing the organ could fool it into thinking it was full. I sat up and looked at Anna, slumbering peacefully beside me in our double cot. I needed to eat more, and I knew if I woke her, she’d talk me out of it. Anna found it easy to follow all of the Church rules. But as long as I was eating the approved food, I reasoned, it shouldn’t do too much damage to my Brightness levels if I ate another serving or half serving. I eased myself out from under the covers and put on my shoes and my sheet. I slipped out through the red velveteen curtains and snuck through the hall to a neglected-looking service elevator. Inside the elevator, the button panel was all blank. I pressed one at random and hoped it would take me to a floor with food on it.

Through miles of Church corridor, on floors where broad windows looked out on a massive parking lot, dark and featureless like this immense building’s even larger shadow, on floors that had no windows and thrummed with the sound of machinery far underground, I searched for food. The structure was clean like a hotel or office building, the carpeting clean and dustless, but there were things piling up in it that didn’t belong: a tilting pile of sequined decorative pillows blocking what looked like an unused elevator bay, cardboard boxes lined up in the hallway that turned out to be full of jars of beauty cream, the one with the commercial where the bird escapes from inside the woman. The creams were heavy and full, store-ready in their crisp red boxes, but when I took off the lid the cream’s surface had a deep swirl in it: not a machine’s smooth finish but something made by hand.

The upper floors had crisp steel numbering and panes of cold glass that revealed dull gray interiors. In the middle, the halls were motel-colored, sullen beige, with smooth neutral doors marked by small brass numbers. The lowest levels of the building — where I wandered, hiking my sheet up to move more smoothly, hoping to find a familiar letter on a door, or any letter at all — looked like a series of bunkers, avocado green and overlit, the signage on the walls outdated and peeling. Each new part of the Church I saw made me think it had once been something else: a hospital, a corporate hotel, an office complex. Even stripped of its former contents, the deep structure of the building held traces of its former use. I wondered if the other Eaters who passed me by could tell by looking at me what I had once been, what I had once bought, what couple of categories I had once belonged to.

On floor six, a tall man under an extra-long sheet with a ragged hem stopped me in the hall.

“What are you doing in Section Six?” he asked, holding me in place with two fingers on my sternum.

“I was just looking for some food and I got lost,” I said.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)