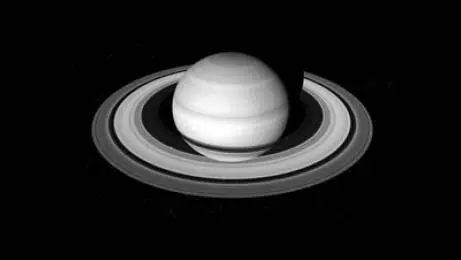

I set up the telescope, fixing it into position, slowly and carefully, pointing it up to the section of the sky where I’d last stumbled across Saturn. I put my eye to the lens, but it’s out of focus. I fiddle with the lens for some time, sharpening and re-sharpening the image, until the abyss above me brings everything together: stars and constellations becoming visible, as if the blackness has willed the universe to acknowledge my presence. I feel like I’m going to fall into it, as if something is about to pull me through the lens towards it, into it, falling into the same incredible blackness. I begin to feel nervous, the same vertigo-like feelings. I need to find Saturn, to see it, to make sure it’s still there: just to witness it hanging there, out there, coming through the night towards me. I delicately move the telescope across the night, sharpening and re-sharpening, my breathing quickens as I pull more of the oxygen around me deep into my lungs, the night air entering me, the same blackness filling up my lungs, fusing with me, as I sink deeper into it. Suddenly I realise I have the wrong lens in the telescope: a x6 mm instead of a x12 mm. I’m seeing too deeply into the night sky, I need to move out, outwards, allowing more of the vast night into the lens, deeper. I quickly change the lens, the blackness as sharp and as crisp as ever. I slowly move the telescope to the right, millimetre by millimetre. It feels like I’m about to pass out.

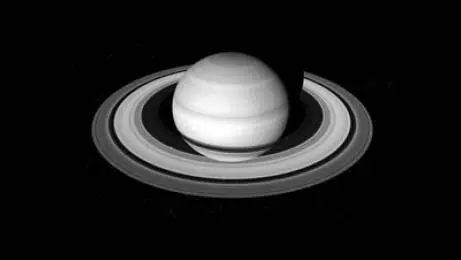

Saturn suddenly appears. It slips into view, like a trick, some sleight of hand. I focus in on it, sharpening the reflected, upside-down image, shaking a little, its back rings higher than the front, its entire southern hemisphere tilting towards me, like a gentleman tipping his hat. Saturn’s declination thrills me: the way it hangs there in the blackness, leaning towards me, for me.

I imagine I’m the only person in the world looking at it right now. I focus in as much as I can, trying to determine each of its seven rings, as much as the lens will allow me before it blurs. Saturn simply hangs there, mysterious in its splendour, frightening and beautiful, a maddening sphere of gas, so real before me it feels like I can reach through the telescope and touch it. It seems to confirm everything; my entire existence: each blemish, spot and milky swirl on its surface representing some mark of me.

I stare at Saturn through the lens until my eyes begin to hurt, making slight adjustments in accordance with the earth’s rotation and movement. But something isn’t right. It doesn’t feel right all of a sudden. Everything is reduced to this yellow-brown marble in the night, everything is sucked into it. My eyes begin to water, and it becomes harder for me to focus on the image, so I take out my phone and turn on the camera so that I can film it through the lens. It strikes me that I’ve never thought of this before. I line up the eye of my phone’s camera with the lens of the telescope, and look through the screen of my phone at the image: at first I’m confronted with blackness, then something incredible happens as I begin to film: Saturn comes into view, a shadowy apparition of what I’ve just seen through the original lens, a pixellated, digitised version, overlapped and over-layered, a recorded image seen in the present. It’s truly beautiful, like a work of art. Truly real.

I stop recording after one minute and fifty-three seconds. I laugh. I re-watch the recording immediately. I laugh at everyone who’s lived a life unaware of its presence, its brilliance in the black night, those who live never looking up at things, never reaching out, afraid to question, afraid to learn finally that there are no answers and there never will be. Things just go on, hanging there in the blackness, surrounded by it, but they go on, things go on, everything goes on.

i know this won’t last

Later on I walk to the creeks below Canvey Heights. The stars seem low in the blackness above me. I can see their reflections in the murky water below. The moon, just up behind me, is low over the estuary, too: yellow, brown, as if trying to emulate Saturn itself. I sit down by the remains of the old concrete barge, stuck rotting in the mud. The air is strangely warm and still; I can hear movement in the water, gentle laps on the muddy creeks. I look up into the dense night, out towards Southend: I can see bats wildly fluttering around, in a swooping figure of eight; beyond them I can see the outline of the old church in Leigh-on-Sea; and below that, the tall masts of the sailing and fishing boats anchored in Old Leigh, along the cockle sheds, deep down into the estuary. Their silhouettes float like black ghosts, or black paint marks on some sombre canvas. I want to capture what I am seeing. I take out my phone and try to take a picture and then some footage, but it’s too dark. Just like in Uncle Rey’s book, I know this is impossible anyway, I don’t know why I even attempt to do it, so I sit and stare, filming anyway. I try to take in every minute detail: the smell of the mud and wild lavender, the blackness, the yellow-brown moon, the wet earth and tough grass beneath my feet, the sound of the water lapping against the mud, the stillness … filming every moment.

I know this memory won’t last, but it doesn’t matter. I know that one day most of it will be formless, dumped in some barren recess of my mind, something almost forgotten. I know that now. It doesn’t matter. The moment has been digitised. I’ll still have that. Uncle Rey’s words are spinning within me. I find it impossible to grab hold of them, it’s as if I’ve disturbed them in my reading of Vulgar Things , spilled them out of their container, where they had been put away. It’s as if I’ve stumbled across a wasps’ nest and accidentally kicked it, but instead of running for shelter and the safety of a locked door, I’ve simply remained and attempted to fight off each and every pesky wasp one by one. I’m finding them hard to shake off, they’re everywhere, they’re buzzing inside me, like a rotten virus. I feel contaminated.

It strikes me as a normal thing to do: to shed my clothes, to step down the muddy bank of the creek and dip my toes into the cold water before sinking into it and fully submerging myself, swimming out into the middle of the creek. I float there on my back, looking up at the stars, the blackness all around me. It feels like I’m weightless, floating in nothingness, like I’m hanging around with everything else in the universe: spinning, expanding, out here among it all: the stars, the planets. Saturn, the fertile planet. Its yellow glow binds me together with Uncle Rey, the island, Laura, everything that has happened to me, for ever entwined with everything Uncle Rey tried to forget, to write out of his life. That one day, like it or not, I’ll forget my own way.

I float on my back, cast out, sown, planted in time. But I don’t want to be rooted here, on the island, with all these people, I want to end what Uncle Rey had tried to begin. I want to destroy everything he’s sown. I need to set light to his work, to reduce it to ashes, send it back to dust. I want to free it, to set it off into the universe — each strand, each particle and molecule of it. It’s all I can think of. I swim back to the muddy bank, clambering up the side, trying to retrace my own footsteps. I slip, caking myself in mud. I pick up my stick where I left it and use that to pull myself up, digging it into the mud for support. Finally I reach my clothes, just as it starts to cloud over. I walk back to Uncle Rey’s caravan carrying them under my arm. I know what I have to do now.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу