In Los Nachos, Guinness in hand, my dad said: ‘Lately I’ve had this feeling that as a species we’re on the brink of something; something that redefines everything. Like when they discovered the world was round instead of flat.’

‘They’re closing in on the God particle… ’

He grimaced. ‘The Higgs boson , you mean. Maybe it’s that at the back of my mind. Although it doesn’t feel that specific, it’s more a general feeling of… ’

‘Vertigo?’

He looked at me. Swigged his pint and grimaced again. Mel said he had mouth ulcers. ‘Yes.’

We ferried the drinks to the rest of them and then went back over to the bar, just the two of us. I said: ‘This brink, Dad. Don’t you think every generation has thought the same thing?’

He cleared his throat. Sipped his drink and swallowed hard. ‘Laura, I’ve been alive for the equivalent of two and half generations now and this is the first time I’ve felt it.’

I did think he was being sincere even though the harder part of me thought: Dad, you’re shit-scared, that’s all this renaissance talk is. You need to feel something mind-blowing might happen before… Before the curtain’s pulled back and you see the man with the megaphone. Or worse still: the great big Fuck All that’s there, waiting, just behind the Irony.

And of course I’d heard him, hadn’t I. At his outer limits. Hedging his bets. It was six months since he’d found out (five months since he’d told me and Mel, on Mum’s insistence, two days before his operation).

A grey day. The world in ugly molecular detail. Stones in the driveway. Dust in the air of the house. I went upstairs to use the bathroom while Mum and Mel sat downstairs not drinking tea out of matching floral mugs. Mel kept saying, I can’t believe we couldn’t tell —as though our ignorance was more horrifying for her than the fact of the cancer itself. I heard him as I got near to the bathroom, whispering at first and then a shout breaking through on certain syllables. At first I thought he was on the phone. I crept closer.

You cunt. You fucking cunt. You waited until I’d retired, didn’t you?

I stood rigid on the landing, knowing how mortified he’d be to know I’d heard him.

Just give me ten more years. Ten more years and then you can do what the fuck you want with me.

We sat down to eat. I ordered a rare steak and a salad and another glass of wine. The waiter took my dad’s order next.

‘I’ll have the beef fajitas.’

‘No, he won’t,’ said my mum.

‘Yes, I will.’

‘Four more months and you can eat all the red meat you want, that’s what Dr. Grayling said. Now behave.’

The waiter looked to Mel. ‘Salmon, please,’ she said.

My dad leaned towards me. ‘I had a bacon sandwich yesterday. Slipped through me like a greased otter.’

‘Bill!’

He turned to my mum. ‘I need iron, woman!’

‘Have some greens!’

‘I’m not a pet bleeding rabbit.’

‘Oh, just let him have the fajitas, Mum,’ I said.

She looked at me. ‘You haven’t been up with him all night when he can’t sleep with cramps. You haven’t washed your bedding five times in twenty-four hours. Mel saw what it was like when she stayed… ’

My dad looked at me. The blotches on his cheeks had joined up with rage. ‘Grayling said he’d never seen someone hold on to so much hair. I walked six miles on Sunday without stopping.’ I nodded. ‘All right, then. I’ll have the grilled chicken and a side salad. With blue cheese dressing.’

My mum waited until the waitress had gone and turned to me. ‘So where are you up to with everything?’

Jim produced a list and a pen from his pocket.

‘What’s that?’ I said.

‘My list.’

‘You have a list ?’

‘I find lists very calming,’ said Mel.

‘I’ll tell you one that isn’t calming,’ Jim said. ‘The guest list. We’ve been trying to keep the numbers down but every person raises a few others. It’s like that mythical beast where you chop a head off and two others sprout up in its place.’

‘Just tell them all no,’ said Julian. ‘If we get married it’ll be just the two of us on a beach. I’m not paying for every piss-taker I’ve ever met to come fill their boots.’ He sat straight and breathed in bullishly through his nose, inflating his lungs to full capacity. It was a way of breathing that said More Oxygen For Me .

I looked at Mel. She didn’t look at me. She didn’t need to.

‘I’ve nearly finished your invites,’ my mum said. ‘And I’ve bought the silk flowers for the table decorations.’

Jim crossed something out on his list.

‘Least I can do,’ my mum said.

Jim’s parents were paying for the wedding.

My mum raised a finger, reached her other hand down under the table and brought out a magazine. ‘And I got this for you, Laura.’ I looked down. Bride Be Lovely . The actor-bride on the front, with her stony whited eyes and rictus grin, looked as though she had been saying BE LOVELY BE LOVELY to herself in the mirror through gritted teeth while getting ready.

‘Thanks, Mum.’

Mel turned to me. ‘Have you picked a dress yet?’

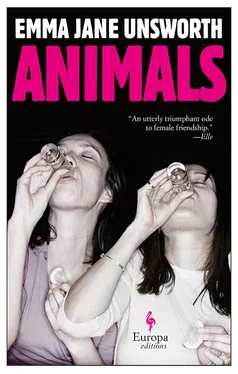

‘I’m going shopping with Tyler at the weekend.’

Julian snorted. He’d first met Tyler at my dad’s sixieth. I could still see his face as he watched her, off her tits on Prosecco, moonwalking across the dance floor to ‘Moves Like Jagger’, shrugging disingenuously. You know what his problem is? Tyler said whenever his name came up. Too much fucking hair gel.

‘Where are you going to look?’ asked my mum.

‘Apparently there’s some kind of bridal village in Cheshire,’ I said. ‘Tyler’s driving me there.’

‘Does Tyler drive ?’

‘You know she does.’

‘Well, goodness knows what you’ll end up with if you’re going with that rum bugger,’ said my dad. This was how my dad referred to Tyler— that rum bugger —with more than a hint of admiration. Unlike the rest of them, my dad liked Tyler because he knew a grifter when he met one and couldn’t help but be enthralled when she wrinkled her nose and told him to Get lost and tell her another.

The last time I’d brought Tyler to a family meal she’d gone to the toilet and come back and sat on my dad’s knee and started telling the whole table about how she’d stood on a chair in the coffee shop that day and recited Beowulf (Medieval Literature MA; she’d got a distinction). She said it had gone down well. I wanted her to shut up — or maybe it was because she was perched on my father’s lap and it was making me queasy. I jerked my head, indicating she should get back in her own seat. She did. Only when the mains arrived and I saw her discreetly slide a cod fillet into her lap and wrap it in her napkin, unable to eat it — flinching as the hot fish burned her thin-trousered thighs — did I understand the real reason behind her sudden eruption of intimacy. Zero appetite. Conversation ramped up to eleven. Busted.

‘So we need to plan a date for a rehearsal sometime in August,’ said Jim, pen hovering.

‘Second half of the month’s best for us,’ said my mum. ‘Last chemo session’s on the twelfth.’

My dad was supposed to be giving me away.

‘Great. But see how you feel nearer the time, Bill,’ said Jim.

‘I’ll be fine, pal, don’t you worry. You just make sure you’re around.’

When we got back to Jim’s I went to the bathroom. As I sat on the toilet I heard him laugh. Rushed wiping, flushing, not wanting to miss out.

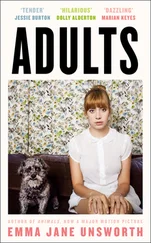

He was sitting on the sofa, the bridal magazine unfurled across his lap. He looked up. ‘Blitz those bingo wings and be strapless without shame! What a bizarre choice of word that is. Shame.’

Читать дальше