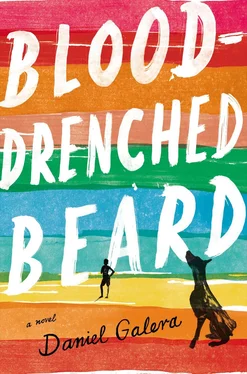

Daniel Galera

Blood-drenched Beard

When my uncle died, I was seventeen and knew him only from old photos. For some unfathomable reason, my parents used to say that he was the one who owed us a visit, and they refused to take me to the seaside to meet him. I was curious to know who he was, and once passed quite close to the town of Garopaba, in Santa Catarina, where he lived, but I ended up putting off visiting until later. When you’re a teenager, the rest of your life seems like an eternity, and you imagine there’ll be time for everything. News of his death took a while to reach my father, who was secluded in a cabin in the mountains of São Paulo, trying to finish his latest novel. My uncle had drowned trying to save a swimmer who fell from the rocks on Ferrugem Beach on a day of stormy seas and ten-foot waves exploding against the coast. The swimmer clung to the float he had given him and was rescued by other lifeguards. My uncle’s body was never found. There was a symbolic funeral in Garopaba, and we attended. My mother showed me the location of the first apartment he had lived in, though it has now been demolished. In old photos you can see the two-story beige building with its roof terrace, right in front of the ocean, above the rocks. There weren’t any tall buildings on the waterfront back then, and the water was still good for swimming. The population of the original village — now heritage-listed — around which the town has grown, still partially made its living from fishing, which has since disappeared, giving way to boat tours. We met his widow, a woman with very white skin covered in faded tattoos, and their two young children, a boy and a girl, both of whom had their mother’s blue eyes. My cousins. There weren’t many people at the funeral. My mother broke down crying, which I didn’t understand, and later spent about half an hour gazing out to sea, talking to herself, or to someone. There were other people staring out to sea as if they were waiting for something, and I had the strange impression that they were all thinking about my uncle, even though he had been described as a recluse whom few people knew well, a man from another era. I decided to film some interviews about him, and my parents allowed me to stay on in the town for a few days on my own. No one knew my uncle intimately, but everyone seemed to have something to say about him. At the beginning of the previous decade, he had opened a small studio, where he taught stretching and Pilates. Most people remembered him as a triathlon coach, and it would appear that half a dozen state and national champions had trained with him at some point. During the summer season, he would put his regular activities on hold to work as a lifeguard. He was the best. He trained volunteers every year. At dusk, after a twelve-hour shift rescuing swimmers, treating cases of sunstroke and jellyfish stings, and walking about under the brutal sun of a southern region devoid of an ozone layer, he was seen swimming alone out in the deep, oblivious to turbulent seas, downpours, and sudden nightfall. He was a solitary man, but at some stage he had married this woman who had sprung from goodness knows where and built a little house on a dirt road that wound its way through the hills of Ambrósio. Everyone who remembers my uncle from the old days mentions a lame dog that swam like a dolphin and that accompanied him out into the deep. And here ends what we might refer to as the facts. The rest of the interviews were a kaleidoscope of overlapping rumors, legends, and colorful stories. They said that he could stay underwater for ten minutes without coming up for air; that the dog that followed him high and low was immortal; that he had once taken on ten locals in a fistfight and won; that he swam at night from beach to beach and was seen emerging from the sea in distant places; that he had killed people, which was why he was discreet and kept to himself; that he never turned away anyone who came to him for help; that he had inhabited those beaches forever and would continue to do so. More than one or two said they didn’t believe he was really dead.

H e sees a bulbous nose, shiny and pockmarked like tangerine peel. A strangely youthful mouth between a chin and cheeks covered in fine lines, slightly sagging skin. Clean-shaven. Large ears with even larger lobes that look as if their own weight has stretched them out. Irises the color of watery coffee in the middle of lascivious, relaxed eyes. Three deep, horizontal furrows in his forehead, perfectly parallel and equidistant. Yellowing teeth. A thick crop of blond hair breaking in a single wave over his head and flowing down to the nape of his neck. His eyes take in every quadrant of this face in the space of a breath, and he could swear he’s never seen this person before in his life, but he knows it’s his dad because no one else lives in this house on this property in Viamão and because lying on the floor next to the man in the armchair is the Blue Heeler bitch who has been his dad’s companion for many years.

What’s that face? asks his father.

It’s an old joke. He gives his usual answer with the barest hint of a smile:

The only one I’ve got.

Now he notices his dad’s clothes, the tailored dark gray slacks and blue shirt with long sleeves rolled up to the elbows, with sweaty patches under his arms and around his bulging belly, sandals that appear to have been chosen against his will, as if only the heat were stopping him from wearing leather shoes. He also sees a bottle of French cognac and a revolver on the little table next to his reclining chair.

Have a seat, says his dad, nodding at the white two-seater imitation-leather sofa.

It is early February, and no matter what the thermometers say, it feels like it’s over a hundred degrees in and around Porto Alegre. When he arrived, he saw that the two ipê trees that kept guard in front of the house were heavy with leaves and drooping in the still air. The last time he was here, back in the spring, their purple and yellow-flowered crowns were shivering in the cold wind. Still in the car, he passed the vines on the left side of the house and saw several bunches of tiny grapes. He imagined them transpiring sugar after months of dry weather and heat. The property hadn’t changed at all in the last few months. It never did: it was a flat rectangle overgrown with grass beside the dirt road, with a small disused soccer pitch in its usual state of neglect, the annoying barking of Catfish, the other dog, the front door standing open.

Where’s the pickup?

I sold it.

Why is there a revolver on the table?

It’s a pistol.

Why is there a pistol on the table?

The sound of a motorbike going down the road is accompanied by Catfish’s barking, as hoarse as an inveterate smoker shouting. His dad frowns. He can’t stand the noisy, insolent mongrel and keeps it only out of a sense of duty. You can leave a kid, a brother, a father, definitely a wife — there are circumstances in which all these things are justifiable — but you don’t have the right to leave a dog after caring for it for a certain amount of time, his dad had once told him when he was still a boy and the whole family lived in Ipanema, in the south zone of Porto Alegre, in a house that had also been home to half a dozen dogs at one stage or another. Dogs relinquish a part of their instinct forever in order to live with humans, and they can never fully recover it. A loyal dog is a crippled animal. It’s a pact we can’t undo. The dog can, though it’s rare. But humans don’t have the right, said his dad. And so Catfish’s dry cough must be endured. That’s what they’re doing, his dad and Beta, the old dog lying next to him, a truly admirable, intelligent, circumspect animal, as strong and sturdy as a wild boar.

Читать дальше