She hadn’t switched on the lamps; the study, if she lifted her head to glance blindly around at it, was eerie in the blue light from the screen. Then the blue was swelled by daylight, which grew outside the window (so it was morning, not night). The rain persisted; the blowing mist became an earnest earthward downpour, soaking and steady. Zoe wrote concentratedly for three hours, only dragging her attention away from the screen when she needed figures and information from the journals and papers on her shelves. Once she went downstairs to put the heat on and make more tea. When she was finally and suddenly too tired to do anymore, she saved her work on a disk and crawled back to bed, still in her socks and sweater. Only instead of choosing her own bed she went on an impulse into Pearl’s room and plowed across the chaos of bedding heaped on the floor to climb under her daughter’s duvet and fall asleep, curled up with her back to the warm radiator, cocooned among all the crumpled dirty clothes, pressing her face into a consoling inside-out T-shirt ripe with Pearl’s young animal smell.

* * *

When pearl rang him said she was leaving home and cried and called him Daddy (mostly she called him Simon, and he had never given her the least sign of wanting anything else), he had thought this might be what he needed, to have a child in the house. He had said she could come for a week or two at least, to see how it went, but in his heart he had for a moment imagined foolish things: how their lives might slip around each other weightlessly in his flat (there would be none of the searing, if none of the excitement, that came with sexual cohabitation), how he might choose books for her and play her music, and how she might with her ingenuousness and chatter heal whatever was soured and thwarted in him. He had even pictured her sitting at his kitchen table, drawing as she used to do, and thought how he would put her pictures up on his fridge and on his kitchen walls, which were too austere. (He used to refuse to put them up, scornful of the smug sentimentality of estranged fathers parading their parenthood. He had kept them instead in a folder in his desk.)

Only Pearl wasn’t a child anymore. She was something else.

Of course, he remembered now, she had given up drawing years ago.

Usually she only came for a weekend, and usually Martha was around to take her off his hands and make sure she was fed and watered and talked to about whatever it was girls talked about (Martha was not a girl but had at least been one, and fairly recently too). Now Martha had gone home to the States for a month, and he and Pearl were painfully exposed to each other. The first morning, he was already convinced he should never have let her come. When he got up at eight he put croissants in the oven and made coffee and squeezed fresh orange juice (he had shopped at the supermarket in honor of her arrival). He called her several times before he realized that, in spite of bleary assurances from behind her bedroom door, she wasn’t going to join him. Then he sat absurdly amid the unaccustomed splendor of his breakfast (he usually only drank black coffee) and ate both croissants.

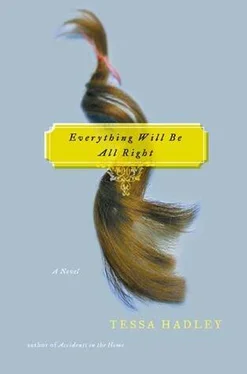

Pearl didn’t get out of bed until well after midday. This should have given Simon a perfect opportunity to get on with his work. However, her mere presence in the flat was somehow catastrophically disruptive. He kept imagining he heard her stirring or calling for him. Somehow the idea of her with her pink hair and her nose stud and her backpack full of female apparatus spilling out into his space prevented him from concentrating (she had explained one surgical-looking item in all seriousness to him as an “eyelash curler”). He gave up trying to push ahead with the chapter of his book and turned instead to reading through a PhD thesis for which he was the external examiner. That was much easier. Pearl could have been one of his students. It was easier to think about her in relation to them. He liked it when the students had pink hair and piercings; he admired their irreverence for what was natural. He didn’t know why he found it disconcerting in his own daughter.

When Pearl did eventually get up, to Simon’s dismay she turned the television on. He had a digital set — widescreen, with the sound wired up to come through his B and W speakers — but he didn’t watch it often and certainly never, ever, in the daytime. (Martha watched things on it that astonished him; he found her unapologetic assertion of a taste for Ally McBeal and Sex in the City provocative and intriguing, but it also made him glad she had kept her own place.) Pearl didn’t have the television on particularly loud, but she didn’t shut the door, and the sound inserted itself like a trip wire between him and the furtive argument of this thesis, which was escaping from him through a dense underbrush of language. (It wasn’t very good: on Dickens and carnival, a stale theme. These enthusiasts for charivari were the same people, no doubt, who complained about joyriders and lager louts.) He found himself trying to determine from the patterns of speech and laughter what it was that Pearl was watching. It must be a chat show. You could recognize the rhythms of inanity without even hearing the words.

He went to ask her to turn the sound down and keep the door shut. She was still in her baggy stretch nightshirt, eating toast smothered in chocolate spread on his white-covered sofa. For a ghostly moment he heard his mother’s words in the room. “Don’t make any marks, will you?” At least he didn’t actually speak them.

— Grotesque, isn’t it? he said instead, after stopping to watch for a moment. “Forgive us for running our item on propagating bonsai in the home, which we know is overshadowed by September’s tragic events, but after all life must go on.” I’ll bet “overshadowed” is doing overtime, isn’t it? And “spirit”? And “inextinguishable”?

Pearl looked at him, pausing with her toast held ready for a bite.

— But what happened was terrible. How else could they talk about it?

— It doesn’t occur to you that if they meant it, if they really meant it, they could just cut the item? Cut the whole show. Turn their backs on the cameras and cover their faces with their hands. We could just contemplate darkness for a few months. It might do us good.

She looked bemused, and then she shrugged.

— But I suppose people expect there to be television. I mean, they might panic, if they turned it on and it wasn’t there.

He contemplated continuing the argument with her but decided that the abysses of her blankness might be too deep. He was not ready quite yet to navigate them with her; he was too afraid of what he might not find.

— No doubt, he said. No doubt there would be panic.

And he went back to the thesis and worked on it for another twenty minutes, until he began to wonder guiltily whether she might need hot drinks or instructions in how to work the shower. Or perhaps she had come to him because she wanted to confess to him, to consult him. Of course if that were the case she should really have got up to have breakfast with him; they might have talked then. She could not expect him to interrupt his work. On the other hand, he was only marking a student thesis. He had put aside his book, his “real” work. He had made his preparations for the week’s teaching. It could not matter if he broke with his routine for just one day. (Martha accused him of living like a monk, with his rigid routines. “In some respects,” she said. “Although a very licentious monk.”)

He got up to suggest that they go out to tea. Wasn’t that what fathers did? He would buy Pearl tea. He would take her somewhere done up to look old-fashioned, she would think Oxford was a charming place, he would ply her with cake, she would consume it with youth’s insatiable appetite for sweet things, and she would artlessly open up to him her life, her reasons for disenchantment with her education, her complaints against her mother. However, when he opened the door to his study he heard that she was talking: not to herself — as he imagined for one disorienting moment (“she’s mad, she’s actually talking to the television”) — but on her mobile phone. Although she was loud with that particular autistic loudness of the mobile phone user, he could not catch exactly what she was saying. The rhythms of her talk were stagey and exaggerated; she sounded like the television she had been watching. He took a few steps along the passage, treading softly on the thick carpet. He had a need to know how his daughter’s mind worked when she was unguarded and apart from him. He could hear her when he stood close up to the closed door.

Читать дальше