It was not quite true that she had made no preparations at all. At the back of the drawer where she kept her sweaters and shirts she had a little cache of baby clothes: some tiny white vests and socks her mother had sent, two little woolly coats knitted by her grandmother, a couple of secondhand Babygro suits she had bought herself from a charity shop because they looked clean and pretty and hardly used. She had blushed when she was paying for them because in spite of her big annunciatory bump she didn’t really feel she was one of the grown-up women who had the right to possess such items. Sometimes when Simon wasn’t in the house she got these things out from the drawer and unfolded them, frowning as she tried to imagine what kind of tiny creature might be fitted inside them.

* * *

And then she was on a trolley being wheeled somewhere and she was looking into Pearl’s eyes and Pearl was looking back into hers. This was not any baby she could ever have imagined herself having. It wasn’t mouselike or curled up or tender at all; it had huge strained-open eyes of dark night blue, staring at Zoe with something like the same indignant awareness of outrage and violation with which Zoe must have been staring back at her.

What was that? The mutual accusation seemed to bounce backward and forward between them. What did that to me?

The last few hours of history still seemed as loud around them as a battle, the blazing assaults of pain, the drama of doors slamming and feet running in the race to the delivery room, Zoe’s noisy vomiting into a kidney bowl, her shouting out numbers at the top of her voice, counting through her contractions. She couldn’t wait to tell her women friends never, ever, to be tempted to put themselves through this; it was much more terrible than anyone could imagine in advance. (Needless to say she quickly forgot it, in her absorption in her new life with the baby.)

— You’ve been so good, the student midwife said, squeezing her round the shoulders.

But this baby didn’t care for any of that.

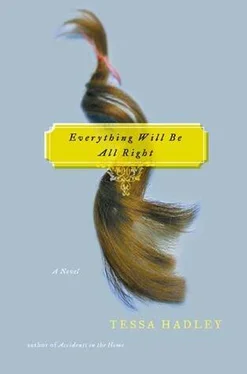

Its hair was not nestling fur but a tall gingery crest. Its nose was broad with flaring nostrils. Its mouth was fat with flat squashed lips, an angry purplish red, downturned at the ends with dissatisfaction.

— Who are you? she whispered to it as they were hurried, staring at each other, down to the ward on the trolley. Where did you come from?

She knew in those first moments that this baby was never going to grow into any elf creature or spirit companion. Actually, she knew in the same moments that the spirit companion had been a silly idea. As if your child could be just a broken-off piece of yourself. Real things were always more tremendous — more unhinging — than the things that grew out of your own thoughts. Perhaps the only thing left over from the dream child was her name. Zoe clung to that, as if to attach to this new creature just a small something of her own, a memory of the wild child from Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter, which she had studied at A-level: Pearl absorbed on the shore in her games with the weed and the shells, loving but free.

* * *

The week that pearl was born, simon was away giving a paper at a conference in Manchester. He hadn’t left a telephone number. Zoe lied on the phone to her mother and said that although he hadn’t been able to get back in time for the birth, he had seen the baby since and picked her up out of her little cot of transparent plastic and held her. She also lied that it was Simon who had first pointed out what now was obvious, that the baby looked like her, like Joyce. Joyce wondered, but vaguely, if she should come up and see them. Zoe, who so wanted her to come, said firmly that it would be a better idea if she gave them a few weeks to settle into their new routine.

The lying to her mother was something new (Zoe usually scrupulously told the truth); it was something that had come about in the rush of change and bloodiness and her attention focused with the nurses on her bodily functions, as if she had lost track for a moment of her higher self. But the hard-edged gap between mother and daughter, narrow but deep, which both dissimulated with bright capable voices, wasn’t new. Zoe would have liked to talk with Joyce about feeding the baby and about nappies, but Joyce’s vagueness warned her off; she remembered their truce of skeptical disapproval, how each politely withheld their verdict on the other. Zoe thought she could guess what her mother thought of her life with Simon; she could imagine her making a funny story to her friends out of how they lived on black coffee and bread and cheese, without a washing machine or an electric kettle, and with a bathtub in the kitchen; how they spent their money on books and music instead of furniture; how when Joyce and Ray came to visit, Zoe had forgotten that they would need spare sheets.

When Zoe had first told Joyce she was pregnant, she had had a sentimental idea that this would lead to a moment of closeness between them, but Joyce at the other end of the phone had seemed shocked and even irritated.

— What about your PhD? she had asked, as if she was actually disappointed, although she hadn’t ever shown much interest in it before. (Zoe, anyway, was convinced that the subject she had chosen to work on — the effects of prewar government education policies on responses to conscription in the First World War — was the wrong one. She struggled on with it, and had folders full of notes and a card index of references, but she found it hard to imagine ever writing it up. She persuaded herself it was more important for her to bring in money so that Simon could write his.)

— Oh, I can pick that up later. At the moment, anyway, it’s not practical for both of us to be studying at the same time.

— But is Simon going to be able to bring in an income to support you while you’re at home looking after the baby?

Zoe had sighed deeply.

— Mum, this isn’t what I want to be talking about, not right now, not when I’ve just told you something important.

— I’m sorry, I can’t quite take it in, that’s all. All the implications.

* * *

— It’s a girl, joyce said to ray, after zoe telephoned from the hospital. She’s going to call it Pearl.

She hesitated in the kitchen doorway as if she didn’t know where to go with the news. It was just after breakfast; Ray was reading the paper and drinking coffee at the big pine table. He took off his reading glasses.

— Good God. Pearl Deare. Sounds like something out of music hall.

— But I suppose it will be Macy.

— So we’re grandparents.

— I can’t believe that, said Joyce. I’m not ready for it. I don’t feel like a grandmother.

— We could just go, said Ray. I’ll fill up the car and check the tires; you throw some things in a bag. We’ll drive. It won’t take more than five or six hours on the motorway. We’ll book into a hotel somewhere in Cambridge.

— I don’t know how to contact her, said Joyce.

— We don’t need to, we just turn up. We know which hospital it is.

— I was seeing Ingrid for lunch tomorrow.

— Cancel her. She’ll understand.

— I’d need to have a bath and wash my hair.

— Run it in while you start to pack. I’ll ring Ingrid.

Joyce put the plug in the bath and turned on the hot tap. Slowly she moved about her bedroom, listening to the tub fill up, pulling out the drawers, walking into the built-in wardrobe and running her hand along the hangers, some outfits still in their dry-cleaners’ bags. Nothing seemed right. She didn’t like anything she had. What could one possibly choose to wear on such an occasion? She pulled out her good gray wool crepe skirt and matching jacket with padded shoulders, but that might be too hot in a hospital, and it would crumple on the journey, and she remembered that the last time she wore it the skirt was uncomfortably tight. There were some black silky trousers that were always comfortable, but the material had gone cheap and snagged if you looked up close, and anyway she had a sudden fear that her thighs looked fat in them, like a barroom tart. She took down one thing after another and threw them on the bed.

Читать дальше