Yet no matter how many hours she spent preparing meals, or helping out with the children or the family projects, there had to be some fragments of time left to her. If she slept less, perhaps. If she rose very early, even before Browning rose to prepare his classes; if she could steal an hour or two for her own work before her family began their demands: then she could feel as if she still had a life of her own. She could do what was asked of her with good grace, if she could have this time alone. The thing was not to give in completely.

As she cleaned up the kitchen and prepared to make yet another meal, she decided to retrieve the tools and materials she’d left behind at the Repository. She’d seen Erasmus only twice since her hurried departure; he was very low and didn’t seem to be working at all. But despite their altered circumstances they could work secretly, she thought. Quietly, in stolen hours and stolen rooms. Still they might do something worthwhile. She stirred Browning’s favorite soup, and then went to tell him she’d be away from home all the following day, and that he must do without her.

COPERNICUS WAS PAINTING in the garden. With Zeke and Lavinia gone on a brief wedding trip, he was taking advantage of his freedom; his loose muslin shirt was open over his chest and his forearms were smeared with paint. Blue streaked his hair and daubed his sweating face.

“Alexandra,” he said. “What a nice surprise.” He darkened a shadow, then stepped back to see the effect. Pinned to a second easel beside him were sketches he’d copied from the notebooks of Erasmus and Dr. Boerhaave. “What brings you here?”

She fanned herself; even the flagstones were sticky in this heat. “I left some drawing materials in the Repository,” she said. “But I can’t imagine we’ll be working in there again. I thought I’d take them home, and see if I can do something there.”

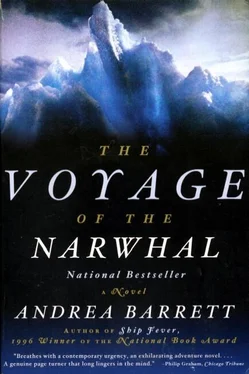

“You won’t work here again,” he agreed. “Nor will I.” He wiped his hands on a rag and gestured toward his painting: icebergs, huge and luminous. In the foreground he’d recently added a stump of broken mast and a ringed seal. “As soon as this one’s done, I’m moving.”

“Where will you go?”

“I have friends at a boardinghouse on Sansom Street — I’m going to take a room there and share the studio on the top floor. I can’t work here, it’s too odd being around Zeke and Lavinia.”

He led her toward the Repository. “You won’t believe this,” he said. “Don’t be shocked.”

Yet she was, when she passed through the high double doors. Inside it was so dim that for a minute, blinded after the glare outside, she could see nothing. Two huge black dogs bounded up to her, bumping their heads against her thighs and licking at her hands—”Zeke’s,” Copernicus said. “He brought them over the day of the wedding.” She wiped her hands on her skirt. Why was it so dark in here? There were skins blocking most of the windows. On the floor Annie and Tom lay in a mass of linen that resembled a pile of sails. Why were there people lying on the floor?

“Hello,” Alexandra said hesitantly. “I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to intrude. I didn’t know you were staying in here.”

Annie had lost weight, and her hair was dirty. “Tseke gave us this as our home,” she said. The dogs loped over and flopped down beside her. “Where is Tseke?”

“He’ll be back in a few days,” Copernicus said. “I promise.” He bent over one of the basins on the floor, dipped a rag in the water, and wiped Annie’s face. “Does that help?” he said. “Is that better?”

“I feel burning,” Annie said mournfully. “So hot.”

Tom coughed and spat. Stains and wet spots and the dogs’ round-toed tracks marked the smooth polished wood; drifts of hair rolled under the furniture.

“Are they sick?” Alexandra whispered to Copernicus. “What’s happened?” Her supplies had been pushed against one set of shelves; Erasmus’s books were scattered and nothing remained of Copernicus’s working area but a stack of crates. By the library table, someone had cast loose herbarium sheets that curled forlornly in the stink sent off by a full chamberpot.

“Zeke moved them as soon as you and Erasmus left,” Copernicus said, close to her ear. “I suppose he thought they’d be better off here than in the house. But they keep shifting from spot to spot, trying to get comfortable. Nothing seems to help but the cold water. They both have fever — I’m not sure whether it’s a reaction to this weather, or something more serious.”

“They’re to stay here?” she asked. “Permanently?”

Copernicus shrugged. “If I had anyplace to take them to, if I had anything at all to say about this — but I don’t, they’re in Zeke’s care.”

In air so foul she could hardly breathe she gathered her things together; her brushes, which she’d arranged carefully, had been jammed upright in a jar and the tips were spoiled. There were dirty fingerprints on the folder containing her drawings, but the drawings themselves seemed intact. Copernicus found a small box for her pens.

They worked without speaking, amid Tom’s cough and Annie’s rough breathing and the heavy panting of the dogs. Once they stepped outside again, Copernicus said, “I don’t know what Zeke is thinking. I really don’t. This is no place for them, they’re miserable here. And the Repository is being ruined. If Erasmus saw this… as soon as Zeke returns, I’m leaving.”

“Where did they go?”

“Washington,” Copernicus said. “Zeke is meeting a group of people at the Smithsonian Institution. They’re making a little party for him there, celebrating his discoveries, and he thought Lavinia would enjoy that. They only went for four days, because of Annie and Tom. Meanwhile I'm supposed to be the perfect person to take care of Zeke’s Esquimaux. As if I’d know what to do with them, just because I’ve had some experience with the Indians out west. But Annie and Tom have different habits and different temperaments from any tribe I ever met — I don’t know what to feed them. I don’t know how to help them, or how to make them comfortable.”

“I’m sorry,” she said. “Is there anything I can do to help?”

“Not unless you know how to nurse them,” he said. “Not unless you know something they’d like to eat. They don’t like the meat I bring them. Annie wants some green plant she says will make her feel better.”

“Some herbs?” Alexandra suggested.

Copernicus spread his hands. “If there’s something you know. I’ll try anything.”

“There’s some tansy and mint in the perennial border.” She led him there and asked for his handkerchief. Side by side they gathered leaves in the burning sun.

“I’ll miss this place,” Copernicus said. “I never imagined, when I came back home, that I wouldn’t have a home anymore.”

The bruised leaves released a scent that began to cleanse the fumes of the Repository from Alexandra’s head. “Is this — is this permanent?” she asked. “You and Erasmus would really let Lavinia take over the house for good?”

“It’s just for a year or so,” Copernicus said. “I think. Zeke’s father has promised to build them a new house, on a plot of land he owns near Fairmount Park. But they have to draw up plans, and then build it — who knows how long that will take. Meanwhile what can we do but humor Lavinia? She’s been through so much.”

“You and Erasmus have been through a lot as well,” Alexandra pointed out.

They knelt side by side in the border. She could smell paint, and the mint they were crushing, and the faint scents of his body and his breath. What would it be like to have him seize her, as Zeke had seized Lavinia on his return? Just as she was thinking this, he reached for a sprig and his forearm drew across her wrist like an arrow across a bow. She froze, thinking how easily she might move her hand a few inches, place her fingers in his palm. Anything might happen after that. He liked her, she knew. Even found her attractive. But he liked everyone; he made no secret of the Indian and Mexican women he’d kept company with out west, nor of die women he met in the theaters here. What she wanted, when she let herself imagine wanting anyone, was someone who might be wholly hers.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу