But this was a punishment, Erasmus thought with dismay, as much as a practical decision. He was being punished for that night in the deckhouse with the drinking men. Separated, purposefully, from his friend. “Let me come,” he said. “Instead of Ned.” He touched Dr. Boerhaave’s shoulder.

“You can’t,” Zeke said. “Why can’t you understand that? I need you here, taking care of the men.”

Dr. Boerhaave stepped forward. “If Erasmus has to stay,” he argued, “why not leave Ned to help him care for the sick? We don’t need a cook while we’re out on the ice — wouldn’t it make more sense to take one of the larger, sturdier men?”

“I need someone I can trust,” Zeke said. “Someone who’ll accept direction without questioning me.”

My fault, Erasmus thought. If he’d managed to placate Zeke, Zeke wouldn’t have turned to Ned.

Ned squared his shoulders. “I’ll go,” he said. “I’d be glad to go.”

“I’m afraid to go,” Dr. Boerhaave confessed to Erasmus later. “I don’t want to, but it’s my duty. What if something happens to Joe or Ned?”

They left the brig on April 16. Zeke made a speech to the men left behind; Ned pressed Erasmus’s hands; Dr. Boerhaave embraced him and whispered in his ear, “Shall a man go and hang himself because he belongs to the race of pygmies, and not be the biggest pygmy that he can?” While Erasmus puzzled over that cryptic comment, the crossing party harnessed themselves to the sledge, heading for the place they’d only heard named once: Anoatok.

IN THEIR ABSENCE, Erasmus bent his energies toward improving the health of his companions. He was stronger than anyone else — perhaps from the grubs, which he ate every day for the rest of April, although no one else would touch them. Each time he ate he thought of Dr. Boerhaave. He let himself elaborate on the daydream he’d had for months: that somehow, when they finally reached Philadelphia, he might persuade his friend to settle there. Just across the creek from his home, a small stone house had been sitting vacant for several years. Dr. Boerhaave might live there, he thought — privately, yet just a short stroll from the Repository. Erasmus would give him a key. They might meet there daily; they might work on their specimens together. Sometimes they might dine together and sit by the fire afterward, reading companionably and drinking soft red wine. Nothing would separate them then.

He decorated that small stone house in his mind: the most comfortable armchairs, the neatest linen. Then suddenly there was wildlife around, and he dropped his daydreams and hunted with a passion and accuracy he’d never known before. He shot a burgomaster gull, three ptarmigan, and two caribou — the first since October. The men ate the venison gratefully and grew stronger. Ivan, the first to recover, helped Erasmus shoot a seal at a newly exposed breathing hole. One seal, then crowds of them climbing out to bask in the sun; Scan and Barton caught two more. Barton, who’d twice worked on a Newfoundland sealing ship, taught the others to eat the dark, oily flesh with slices of fresh blubber, disconcertingly sweet and delicious.

The succulent beef of the first musk ox Erasmus shot roused the last of the men. They cleaned the winter’s accumulation of soot from the beams and walls, aired the squalid corners, laundered bedding and socks and shirts. Only Captain Tyler and Mr. Tagliabeau remained in their bunks. When exhausted by sickness, Erasmus remembered his father saying, elephants will lie on their backs and throw grass toward the sky, as though beseeching the earth to answer their prayers. The elephant is honest, sensible, just, and respectful of the stars, the sun, and the moon — qualities rarely apparent even in man. Just then Erasmus would have happily traded Captain Tyler and Mr. Tagliabeau for a pair of useful pachyderms. He tried alternately to bully and coddle them, but they would not be moved.

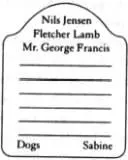

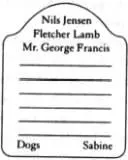

Since Zeke’s departure they’d collapsed entirely, as if finally giving in to their grief over the loss of Mr. Francis. Or as if they no longer believed they wouldn’t share his fate, despite the vibrant signs of spring. In his bunk, above his pillow, Captain Tyler had pinned a small sheet of paper. On it he’d drawn the outline of a gravestone and written:

He and Mr. Tagliabeau wouldn’t hunt, or work on repairing the brig, or pace the promenade. They lay in their bunks, openly drinking and reading as if this might somehow save them. Mr. Tagliabeau burrowed into a copy of Pendennis; Captain Tyler into Dr. Boerhaave’s David Copperfield, picking up where the doctor had left off reading aloud during the worst days of winter. When the men came by their bunks and said, “What should we do? What are your orders?” Captain Tyler and Mr. Tagliabeau shrugged and said, “Do what you want. What Mr. Wells says. It won’t make any difference.”

MAY 5, 10, 15. Still the sledge party didn’t return. Erasmus worried about them — but only for their own sake; whatever meat they brought back from the Esquimaux would now be superfluous. The weather stopped chewing at them and twice the temperature rose above freezing. The light made it feel warmer; the light made up for everything. When Erasmus woke and first stepped outside, the dazzling whiteness pierced his eyes and made his head swim until he treasured the nights, when the sun sat lower in the sky and lent shades of red and yellow to the clouds. A soft mist hovered over the hills and the falling snow was heavy and wet, like spring snow back home. Home, where he might one day live in the company of his friend. What would it mean, he imagined asking Dr. Boerhaave, to grow up hearing stories in which truth and falsehood are mingled with the minerals in granite? To which Dr. Boerhaave might reply, It could mean you were being taught to understand that anything you can imagine is possible.

The brig was still frozen in solidly, but trickles of water seeped down the sides of the icebergs and the floes were bare of snow, sometimes wet on the surface. The broad strip of land-fast ice began to crack as the tides nibbled away at the base, and rocks tumbled down upon it from the cliffs above. Nothing like a lead opened in the solid sea ice of their cove, not even a crack appeared, but the signs of breaking up were everywhere.

Erasmus gathered the men on May 17. He was in charge now; he accepted it. Dismissing entirely Zeke’s dreams of heading north, giddy with sun and the birds in the sky, he said, “I propose we break up the storehouse. The ice might begin to open any day now, and we should be prepared to stow the brig swiftly.”

“Then we can go the minute a lead opens up,” Isaac agreed.

They made heaps and towers on the ice and then slowly began moving the things they were least likely to need back into the hold. Erasmus, Scan, and Barton, with the guidance of Thomas, tore down half the deckhouse and closed off the remainder roughly. Erasmus began sleeping in that breezy shanty, and soon the men abandoned their stuffy quarters and joined him, leaving only Captain Tyler and Mr. Tagliabeau below.

Thomas said, “Should we rebuild the bulkhead? We’re not so dependent on the stoves anymore, and Commander Voorhees will surely want the regular arrangements restored for our voyage back.”

“Leave it for now,” Erasmus said. “It’s a day’s work; we can wait and see what he wants to do when he returns.”

As their spirits rose they knocked down the remains of their autumn ice village and rebuilt it more elaborately. A Greek temple rose white and elegant, next to a model of the Boston library and diagonally across from a miniature tavern which, Thomas swore, was just like the one nearest the wharf from which the Narwhal had sailed. Scan built a railway station and Barton, not to be outdone, built an imitation Japanese garden. Erasmus thought the men built even more gleefully and skillfully than they had in the presence of Zeke, perhaps because they knew each building raised was temporary. Not something they’d have to regard all winter, soiled and slumped and covered with snow, but a living, glistening thing that might dissolve in a few weeks. To their efforts he added a boathouse, with a little river carved before it and curving toward home.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу