“You ain’t telling me there’s an ocean close.”

“It don’t have to be close, Dew. This runs into the Blue Lick River which feeds into the Ohio, and that goes into the Mississippi, and you know where that goes, don’t you.”

“Goes to Mississippi.”

“Well, yeah. But after there, that water runs into the Gulf of Mexico.”

“I don’t know,” Dewey said. “I never heard of no Mexican Ocean.”

“It ain’t a ocean. It’s a gulf.”

“Now, no, Rundell. Mexico is a country, ain’t it, Virge?”

“Right.”

“See there,” Dewey said. “No sense in a man who don’t know Mexico’s a country getting briggety over creek water.”

After lunch, Virgil lay beside the creek, listening to it splash against rocks. His father had grown up in an ancient log cabin that was still standing two counties over. It was on a farm that had been willed to another family branch as a means of punishing Virgil’s grandfather for slights so trivial that no one recalled them. Virgil had long wanted to buy the cabin. He would dismantle it and move it to a spot beside Clay Creek. He’d rent a mini-dozer and carve a road that wound through the woods. Virgil had been saving money for five years. He had never told anyone his plans.

“Here he comes back, by God,” Rundell said.

Virgil opened his eyes, blinking at the abrupt light. Taylor slung aside willow branches and kicked at a rock.

“Look at him,” Rundell said, “Hey, Taylor, ain’t you done a little early?”

“She’s a goddam prick-tease if ever I saw one,” Taylor said. “Wasn’t wearing enough clothes to wad a shotgun and stood there like a pullet with her lungs hanging out. I should have slapped the taste out of her mouth.”

“Got him a way with women,” Rundell said, “don’t he?”

“My opinion, she’s a damn lebanese.”

“Then what was all that man’s junk doing laying outside her trailer home?”

“She just don’t know it,” Taylor said. “Worse kind of lebanese there is. Only knows what she don’t want.”

“And what she don’t want,” Virgil said, “is you.”

“The worst I ever got was better than any you ever had,” Taylor said.

Virgil didn’t answer. Taylor talked five quarts to the gallon, but he never fought.

“What you ort to get is some rest,” Rundell said.

“I got eternity for that,” Taylor said. “Biggest thing I’m afraid of is getting old and regretty. I got me a uncle that way. Sumbitch just sets. Wouldn’t hit a lick at a snake. All he talks about is what he never done. About like Virgil’s going to be one day.”

“I do what I want,” Virgil said. As soon as he spoke, he wished he hadn’t.

“It’s what you don’t do that you regret. And they ain’t a man of us that don’t know what you ain’t doing.”

“What?” Dewey said. “What don’t we not know?”

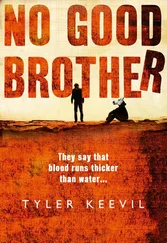

“That Virge here’s letting that boy who killed his brother walk around.”

Virgil’s insides felt hollowed out.

“The way you act,” Taylor said, “they could start picking off the rest of your family. Was me, I’d do some waylaying.”

“It ain’t you,” Virgil said.

“They’re lucky it ain’t,” Taylor said. “Only one thing to think of a man lets his own brother rot without doing nothing. He’s chicken, ain’t he, Dewey,”

“Yellow stripey.”

“Cluck,” Taylor said, “Cluckety-cluck.”

Virgil stood slowly. He was trembling, and sweat rushed down his body. His entire world had shrunk to a narrow cylinder of vision that ended at Taylor. He moved toward Taylor, who took two steps back.

Rundell rose swiftly from the grassy bank.

“Taylor’s a damn fool and you know it,” Rundell said to Virgil. “Ain’t worth the powder it’d take to blow his brains out.”

Virgil slowly sidestepped him. Taylor backed away until he was against the trunk of a locust. He arched his back from the sharp thorns that carried its seed. Virgil stopped with his shirt an inch from Taylor’s narrow chest. He was eye to eye with the locust thorns above Taylor’s head, Birds ate insects that were blown onto the spikes, and after a fierce storm, he’d seen spindled birds eaten by a raccoon. If a wind came big enough to drive the coon into the barbs, he supposed a man would eat the coon. He wondered what animal would eat a man who got hung on the barbs, and the answer surged forward: a man would eat him.

He leaned his face to Taylor’s until their noses touched. When he spoke, his lips brushed Taylor’s mouth.

“I ain’t that hungry yet.”

He moved away from Taylor and down the slight slope and stepped into the creek. Water spiders scuttled from his shadow. Crawdads jerked backwards as if yanked by a string. The hollow opened and the creek became shallow, marked by ripples and tiny dams of trash. He walked steadily, his legs wet to mid-thigh. He climbed the bank through a high patch of ragwort. Riled bees flew tight arcs of warning before returning to their work. A frog hopped into the water and Virgil sat on a rock where the frog had been. A ladybug landed on his leg. The air was heavy with the musk of life.

He began to relax in the one place where he felt safe. He’d spent half his childhood in the woods, much of that time with Boyd. Among the oak and maple, pine and hickory, he had a sense of belonging that had always eluded him in the company of people. He tossed a rock into the creek. As a kid he’d supposed that all objects were sentient and had envied rocks their perfect existence. Nothing was expected of them. He and Boyd had spent hours discussing the imagined opinions of a tree, the road, or a cloud. Did a shovel enjoy digging? Did coal mind being burnt? Would a chunk of ash rather be a baseball bat or an ax handle?

The sound of the creek steadied Virgil’s thoughts. He remembered Boyd as a child climbing a tree and leaping to a sapling, which bent with his weight and eased him to the earth. Virgil climbed the tree. He stood on the limb for a long time, afraid to jump. Finally he’d climbed to the ground and headed home.

Now a red squirrel watched him from a log gone to peat, then fled through swaying fronds of cinnamon fern. Virgil began walking the creek bank. The air cooled as the hollow narrowed. He reached a split in the creek and took the smaller fork, a trickle that led into darker woods. Trees were huge and ancient, the land being too severe for logging. Birdsong rose and fell around him. The dense canopy allowed sun in a flowing mosaic of darkness and light. The creek ended at a rock wall green with moss and Virgil climbed the hill, following a crescent of pine.

The slope was steep and he moved in a crouch, his body close to the earth, limbs spread like a spider. At the spine of the hill he rested. Though he’d never been here before, he knew where he was. Town lay one direction and the rest of the world the other. He walked four miles along the ridge top before the last of the anger left him.

The smell of wood smoke drew him to a thin column of gray rising from a house. The back door was painted green to ward off witches. He circled the house to approach it from the front and a dog ran at him, barking. A board path was embedded in the yellow clay dirt. There was no grass. The topsoil had been scratched away by chickens, leaving veins of clay that ran between exposed tree roots. Tarpaper covered the house and an oak shoot poked from the roof. Green moss clung like velvet beneath the eaves.

A woman sat on the porch with a pistol in her lap. She stripped the ribs from a wide leaf of tobacco and pushed it in her mouth. Near her chair was a bucket and dipper.

“Where’d you up from?” she said.

“Ridgeline.”

“Fall off a train?”

“Walked from town.”

Читать дальше