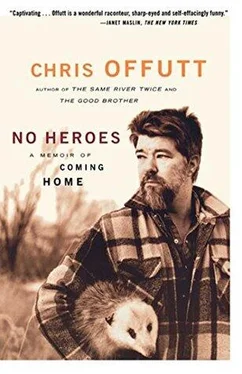

Chris Offutt

No Heroes: A Memoir of Coming Home

To Mrs. Jayne, my first-grade teacher

A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his own image.

— JOAN DIDION

Portions of this book appeared in various forms in The New York Times Sunday Magazine, River Teeth, ACE Magazine, and OK You Mugs.

For providing time and space to work, the author wishes to thank Yaddo and Minnow.

No matter how you leave the hills — the army, prison, marriage, a job — when you move back after twenty years, the whole county is carefully watching. They want to see the changes that the outside world put on you. They are curious to know if you’ve lost your laughter. They are worried that perhaps you’ve gotten above your raisings.

To reassure the community, you should dress down except when you have to dress up, then wear your Sunday-go-to-meeting clothes. Make sure you drive a rusty pickup that runs like a sewing machine, flies low on the straight stretch, and hauls block up a creek bed. Hang dice from the mirror and a gun rack in the back window. A rifle isn’t necessary, but something needs to be there — a pool cue, a carpenter’s level, an ax handle. Where the front plate should be, screw one on that says “American by birth, Kentuckian by the grace of God.”

Be polite to everybody. Even if you are certain you have never seen this lady in your life, ask how her family is. No matter that this man once tore you up one side and down the other, the worst skull-dragging in county history, let bygones be bygones. Smile and nod, smile and nod. When a conversation ends, always say “See you in church.”

Tell them it’s a big world out there. The desert is hotter than Satan’s Hades. The Rocky Mountains are higher than our hills. The ocean is polluted, cities smell bad, and a working man never gets ahead. Don’t talk about the beautiful people in stylish clothes. Never mention museums, the opera, theater, and ethnic restaurants. Forget the time you visited a movie star in his home, drank a thousand-dollar bottle of wine, or rode all over Chicago in a limo. That sunset walk across the Brooklyn Bridge doesn’t hold a candle to crossing Lick Fork Creek on a one-man swaying bridge. Fine dining will make you fat, but fresh butter on corn bread will make you cry.

Take home as many books as you can. Every bookstore at home for fifty miles is heavy on cookbooks, mysteries, and romance, but a little short on poetry. Remember, poetry in the hills is found, not written. It lies in the handles of tools passed down through families, an ax sharpened so many times the blade is the size of a pocketknife.

Bring palpable evidence of where you’ve been. Take back objects to hold and smell — no photographs. Take back a stuffed possum, subway tokens, a hockey puck, petrified rock, a porcupine quill, a buffalo hide. Be prepared at all times to say it’s better here. You spent twenty years trying to get out of Rowan County and twenty more trying to get back.

Before you leave the city, don’t forget to borrow CDs from your friends and make copies of music no radio plays and no store sells. Jazz in the hills is a verb, and pop is what you drink. The Motown sound is a sweet rumble made by muscle cars. Soul is the province of the preacher, and the blues is what going to town will fix. Remember, you won’t ever get tired of sitting on the back porch facing the woods with a group of people playing banjo, guitar, mandolin, and fiddle. They will make music through dusk and into the night, a sound so sweet the songbirds lie down and die.

Now that you’ve got a houseful of what you can’t get, think about what you don’t need anymore. Best left behind is the tuxedo. You’ll never wear it here. May as well trade your foreign car for American if you want to get it worked on. You’ll not need burglar alarms, bike locks, or removable car stereo systems. The only gated community is a pasture. The most important things you can get rid of are the habits of the outside world. Here, you won’t get judged by your jeans and boots, your poor schooling, or your country accent. Never again will you worry that you’re using the wrong fork, saying the wrong thing, or expecting people to keep their word. Nobody here lies except the known liars, and they’re great to listen to.

No more will you need to prove your intelligence to bigots. You can go ahead and forget all your preplanned responses to comments about wearing shoes, the movie Deliverance, indoor plumbing, and incest. You don’t have to work four times as hard because the boss expects so little. You don’t have to worry about waiting for the chance to intellectually ambush some nitwit who thinks you’re stupid because of where you’re from.

You won’t hear these words spoken anymore: redneck, hillbilly, cracker, stump-jumper, weed-sucker, ridge-runner. Never again will you have to fight people’s attempts to make you feel ashamed of where you grew up. You are no longer from somewhere. Here is where you are. This is home. This dirt is yours.

Kentuckians have a long tradition of going west for a new life and winding up homesick instead. Some went nuts, some got depressed, and some made do. I did a little of all three, then got lucky. I finagled an interview for a teaching position at the only four-year university in the hills. It was more of a high school with ashtrays than a genuine college. I should know. Twenty years ago I graduated from there.

Morehead State University began as a Normal School to produce teachers for the Appalachian region, then progressed to college status. During the 1960s it became a full-fledged university, but natives still referred to it as “the college.” Very few local people attended MSU. I had gone to grade school, high school, and college within a ten-mile radius. It wasn’t until much later that I understood how unusual this was, particularly in such a rural environment.

As a theater and art student I supported myself by working part-time for the MSU Maintenance Department. Few of my fellow workers had finished high school and none had gone to college. According to hill culture, you were a sinner or an outlaw, a nice girl or a slut, lived with your folks or got married, worked at maintenance or went to college. This either/or mentality is a product of geography. Land here is either slanted or not, and you lived on a ridge or in a hollow. That I was simultaneously engaged in both attending college and working at maintenance astonished my coworkers and faculty alike.

I worked on the painting crew specializing in the outdoor jobs no one else wanted. Many times I painted a curb yellow in the morning, then stepped over it on my way to class that afternoon. Teachers ignored me when I wore my work clothes. My maintenance buddies felt uncomfortable if they saw me going to class, and I developed the habit of eating alone to conceal the book in my lunch bucket. Now I was back to interview for a job as an English teacher.

Before the interview I borrowed a tie from Clyde James, a man who’d been my neighbor and baby-sitter when I was four years old. He now ran the MSU student center. Clyde was something of a clothes horse, and rumor had it that his closets were carefully organized so that he didn’t wear the same outfit twice per year. My lack of a tie was no surprise to Clyde, who was delighted to assist me. After narrowing his choices to three, he picked a tie that vaguely matched my slick clothes — dark pants, light shirt, tan jacket. I’d bought a brown belt for the occasion, my single concession to formal dress. Clyde thought brown shoes would have been better than black, but I could pass. He deftly tied a half-Windsor knot, looped it beneath my collar, and adjusted it to a snug fit. The material was blue and gray silk, with a touch of red — perfectly conservative. He smoothed my collar and sent me out, calling me “Prof Offutt.”

Читать дальше