I stepped outside and spoke briefly to a man I remembered from high school. I vaguely recalled something bad about him, but I could not trust the memory because More-head thrived on innuendo, scuttlebutt, and outright lies. When I was a kid Rowan County had telephone party lines that included two to eight families. No conversation was private. The telephone functioned primarily as a method of disseminating information to all the eavesdroppers along the ridge. Gossip was the mortar that held Morehead together. Everyone lived downstream of rumor.

I entered the bank through doors I’d opened a thousand times — first with my mother, then later on my own. Thirty years ago I began a savings account here, depositing a dollar a week until I bought a bicycle. Now I sat in a fake vinyl chair and smiled politely at the employees. Out west I was one of the perpetual faces with no history, a drifter, a stranger, a man from the east. Here everyone knew my entire line — root, branch, and fork.

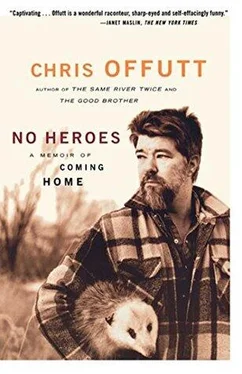

Wearing blue jeans in the bank meant I was a local. The gray in my hair meant I’d been away. My very presence meant I sought money. By the end of the day, word of my impending return would spread throughout the county. Some stories would have me moving in with my folks — because one of them was very sick. Another had me purchasing my old grade school and converting it to an art colony. I was living in a houseboat on Cave Run Lake. I had AIDS and came home to die. My wife had left me and I was back to hunt another. One story said it wasn’t Chris Offutt but his younger brother who was investing in the new mall. When the truth finally outed, everyone knew I was not living where I grew up in Haldeman, but had bought the old Jackson place, which meant I must be doing well for myself because they were asking a pretty penny for it. On top of that, somebody else said I was teaching at the college, but no one believed the college would ever allow that.

My high school baseball coach came into the bank. Twenty-five years ago we placed second in the State Tournament. I attended every game as team statistician.

“Hello, Coach,” I said.

“Why, Chris Offutt. I thought you died in Vietnam.”

“I’m too young.”

“How’s your mom and dad?”

“They’re doing good, Coach.”

“Looks to me like you growed some.”

“About six inches.”

“I’ve got a videotape of when we won the regional tournament. One old boy frog-jumped right over you. Just put his hands on your head and pole-vaulted. You should come and see it.”

“I’d like that,” I said.

We grinned at each other, unsure what to say next. He doubled as the driver’s education teacher and I wanted to tell him I still drove safely. That sounded like something a moron would say, so I remained silent. In high school I never shut up and the coach seemed puzzled by this change.

The vice president of MSU Personnel, whom I’d met earlier that day, walked into the bank. I was afraid he’d suspect that I was negotiating a house loan before getting the job. An official offer still had to clear his office, and he could put the kibosh on my plans as easily as brushing away a fly. Terrified that he would see me, I walked quickly away, stepped into a narrow hall, and peered around the corner into the main part of the bank. The vice president was thumbing through his checkbook. Beyond him the coach stared after me as if I were a video he was trying to replay.

I hurried to the bathroom and locked myself in a stall. The door opened and someone entered. I climbed onto the toilet so no one could recognize my shoes. I crouched to prevent my head from appearing above the partition. In a small town you see the same faces several times a day. The by-product of such familiarity is secrecy and paranoia, and I was already beginning to fit in.

Eventually I became embarrassed and stepped boldly into the bank. The coast was clear of university muckety-mucks and high school teachers. The loan officer led me into a large office, where we talked for twenty minutes. I told her that MSU had already offered me a job. I told her that the salary was double what I actually expected. I told her that I had journalism work coming out of my ears, foreign rights sold in countries as obscure as Tasmania, and movie deals pending left and right. Everything I said seemed to please her and the more pleased she became, the more the lies flowed from my mouth. She gave me some financial forms that I filled out rapidly. Her family had owned the corner drugstore where I read comic books on Saturday. She recalled having sold me Cokes for a nickel. Her brother was fine; our parents were fine; our spouses were fine. She said the loan was fine.

I walked to the corner drugstore to celebrate with a Coke, but the space had been transformed into a pet store that reeked of urine. The Trail Theatre was closed and the post office had been converted into the police station. I had just bought a house without a job, based on crying in the woods. The hills surrounded me like the dome walls of a snow globe that you shake. Everything in my life was turned over and I was waiting for the flurries to settle. Home, I told myself. I’ve come home.

I drove to a hotel on the interstate where the desk clerk was a friend of my sister’s and the waitress was an old high school teacher. Screwed to the wall of my room was a framed print of a barn with a fading mural that said “Chew Mail Pouch.” I unpacked and stared at the ceiling. I needed to call my parents, who still lived in the family home ten miles away. If I failed to call, they’d be upset, but if I did call, I’d have to explain my preference for a hotel room over their house.

I dialed the number that I knew by memory all my life. My parents each listened on an extension. I told them that MSU was paying for the hotel room, and before they had a chance to respond I said I’d found a house. My father asked where the house was. I told him it was off 32 going toward Fleming County, and he said too bad it wasn’t closer to their house. My mother said it was closer than Montana at least. That’s true, my father agreed, and they began talking with each other, a phone habit that was only truly bothersome if you were calling long distance and didn’t feel like paying for them to communicate from different floors of the house.

After a few minutes of listening to them discuss a leak in the roof, I told them I was leaving in the morning but I’d be back in a few weeks.

“Give my love to the boys,” my mother said.

“And Rita,” I said. “Don’t forget Rita.”

“Rita, too,” my mother said.

“And Rita,” my father said. “You cant tell from the drip where the leak comes in.”

“That’s right,” my mother said. “It could be anywhere.

“The chimney,” my father said, “that metal part at the shingles.”

“Flashing,” my mother said. “It’s called flashing.”

I hung up the phone gently so as not to disturb their conversation. I called Rita and the busy signal throbbed in my head. In the past year I’d suffered my most severe bout of homesickness, a gradual descent of misery to the embarrassing trough of crying over a recipe in an Appalachian cookbook. My sobs awakened Rita who joined me in the living room. She had never seen such grief in me, and assumed it could only be the result of a phone call bearing terrible news. In a tender voice she asked who died. I didn’t have the heart to tell her I was mourning my own loss, that a part of me had died the day I left the hills. I was like an amputee feeling perpetual pain in my phantom limb.

The Rowan County phone book consisted of seventy pages and I searched unsuccessfully for a house inspector. I read the white pages for an hour repeating the last names like reciting a prayer. I knew the family histories — where they lived and what ridge or hollow they came from. I had dated them and hated them, fought them and sided with them. I knew their parents, brothers and sisters, first and second cousins. Soon enough I’d know their children. The addresses flowed through my mind. I’d walked the dirt and driven the roads and gotten lost a hundred times. The names were the sounds of home, the language of the land.

Читать дальше