I really should bring it back here with me, she shouts.

What do you need to bring with you, I ask.

She clatters the dishes, putting them into the dishwasher, pushes the door closed. The song is finished, there is someone talking now.

She stands in the living room doorway. Helena, who has always been the youngest. She sits down beside me, stretches out her arms and embraces me, rocking. I accept the sign of affection and hug her back. If you fill out the form, I’ll fetch it for you meanwhile, she says.

What, I ask.

The book, she says.

Why does it not matter anymore, I inquire. What do you mean?

I just mean that I won’t actually be able to tell him if I like it, we aren’t going to be able to discuss that book now.

She strokes her hair with her hand as she speaks, pulling it behind her ears. I can bring it to you, she says. I can come in again afterward in any case.

Yes, I say.

Mom, she says, giving me a hug.

And then she leaves.

SHE WANTS TO return the book she has borrowed from him, as though there really is a rush. An hour later she phones to say that it took awhile to find it. As though I have asked her to do it, as though there is a hurry and it’s important. Take your time, I say. I’m here.

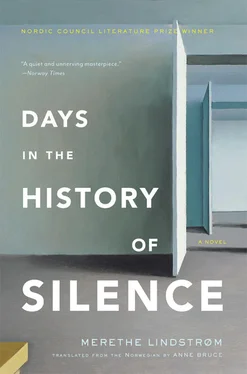

But just after that she is standing in the house again. With the book and frozen raspberries she was out picking in our garden earlier in the summer. Everything is contained in two bags. She couldn’t be bothered to read it. Although she feels, she says, that he still wants her to do it. The book means something, he was so enthusiastic about that author, the historian who has written it. They talked about it. It was one of the last conversations they had together, when Simon at least spoke a complete sentence to her. Perhaps that was why it seemed so important, she says. She has picked up the book, placed it on the coffee table.

We remain standing for a moment.

I’m always trying to guess what you’re thinking, Mom. Are you? I say. You know I talk all the time. No, she says. You don’t.

I OBSERVE MY daughter, the dark hair, the blue eyes. Exceptionally blue. Simon’s eyes. I study Helena, there is something I have always regarded as glassy, brittle, about her. She was always afraid when she was little, afraid of the water, of the attic, of the dark.

Perhaps it comes from the fear she has inherited without actually knowing what she is scared of, could not know.

At one time I must have thought it would protect her. Not knowing, that it would make her, make them, safer. But when I look at her now, it strikes me that it has had the opposite effect. Maybe it works that way, that what you guess at terrifies you more than what you are told. The blurred, nameless apparition.

As a child she invited friends to visit on her birthday. They arrived in starched party dresses, eight eleven-year-olds, stiffly dressed up and critical, going around looking at everything we had in the house, lifting things up and peering at her belongings. No one talked to her, they ate our food, delivered their presents, chatted together in her room without letting her in. She did not complain, I think she was afraid I would be angry with them.

A few hours later, they traipsed home.

I don’t know why, there seemed to be no reason. When I asked her, she just said that she was not very popular.

In time she became like me, like us, she began to read, withdrawing more into herself. Her sisters are tougher. Helena is the only one who is a teacher, like me. She teaches science, mathematics, nothing as intangible and vague as literature. I think it is an appealing subject. She teaches at junior high school, I like the thought that she stands facing them, explaining something so solid and certain.

I take one of the bags with me into the living room. I still feel uneasy, perhaps I have acquired her uneasiness. The clock is ticking, suddenly I hear it.

She leaves, and I think about the application form. That she forgot to ask me if I had filled it in.

I REMEMBER SOMETHING that happened once when we were on the way home from a trip to the mountains, just Simon and me, we had been driving for hours, we were on our way down after staying at a little hotel for a few days, it was some occasion or other, and we were driving through a valley that reminded us both of some other place, a place we had been before and enjoyed. We were exhausted. Hungry and thirsty. As we drove over the newly paved highway, I saw a sign saying BYGDETUN, a local museum. I recalled something like this from my childhood, a vague memory of a day spent in the sun at some place like that, and there was the same heat outside the windows while we were driving that day. I said that to him, we could stop, I said. We could get something to eat.

Simon wasn’t sure, he drove on, I thought he wanted to pass up the idea. But he pulled onto the side at an exit road and turned the car.

It was later in the day than I had realized, and when we parked the car in the row of other vehicles, I saw that people were already on their way out of the museum, though there was still no sign of anyone dismantling stalls or packing up. Children at one end of a playground were having a good time with a pony, two boys on the stage were trying to grab hold of the microphone, talking into it, splitting their sides with laughter, but the equipment was obviously switched off. There were still families sitting on the wooden benches with thermos flasks and coffee cups. But there weren’t many people all the same, and perhaps it would have been different if it had been more crowded, if there had still been a queue in front of the stalls as I expected there would have been earlier in the day, if people had their eyes focused on the stage, at something going on up there. It didn’t take long until it dawned on me that we had become an attraction, although that is the wrong word. We were being noticed, or more than that. Passersby were looking at us skeptically, I thought it was skeptically, at least there was no feeling of being welcome. What I had been trying to relive, the pleasure I remembered from the encounter with a similar museum as a child, had completely vanished. Instead I was the stranger, we were the two strangers, who had sneaked into a location where we did not belong.

We continued to stroll around for a while, Simon bought a cup of coffee, I looked at a hand-knitted scarf, I felt I was being watched. Even by the children.

When we returned to the car, we did not speak. We had both, I am quite certain, the same realization of not being wanted. It was a feeling of shame, that we might have misunderstood, read the signs of hospitality so wrongly and believed that it embraced us, that we also without any fuss might fit in and be accepted.

She enjoyed cleaning, Marija told me. As a rule she simply went into a house or an apartment, let herself in with the key she had been given or a key that was hidden somewhere. She worked her way through the house with a mop, a vacuum cleaner. There was nobody there, no instructions. Few of the houses were really dirty. She cleaned just as thoroughly regardless. She saw little of the inhabitants who must live there, who rarely left behind any traces other than an almost invisible hair on the basin, a towel on the kitchen floor, a pair of sneakers in the hallway. Of course also the money that was left for her on mantelpieces or dining tables, and in some cases, as with us, paid into her bank account. She might discover a coin placed in a strategic spot or a banana skin that seemed to have slipped out of the trash can. A kind of test, she thought.

In one place lived a married couple. At first Marija had thought they were just living together, that he was a relative, or that they were siblings. Because it seemed as though they lived separate lives and seldom spoke to each other, she said. But they were husband and wife. The man liked to sit and talk while Marija went about her work, he chatted about his wife. He nattered about his wife who was sitting on the other side of the wall and who was walking outside in the hallway, between the bathroom and the kitchen, as though she was someone who had left the house and disappeared long ago. Or he talked about their summer cottage and the grown-up children who were there far too often, he rambled patronizingly about their habits, in-laws he could not abide, about journeys they made to places he could not comprehend anyone having any interest in visiting. Every time she was there, he turned up to talk to her. He could sit for many minutes with his observations, talking continually as time passed and Marija tried to work. She had the impression it was not the floors and the cleaning she was being paid for, but that she was actually being paid for conversing with this man, Marija said to me. And there was some kind of inference. Something was being implied through this arrangement. That social barriers were being expunged, something was being assumed that she struggled to understand.

Читать дальше