“I really wanted to just do something horrible to her.”

I think it’s pretty clear where I get all this from.

I have a friend by the name of Eugene Flynn. Eugene owns several very successful restaurants in Hoboken: Amanda’s, the Café Elysian, and Schnackenberg’s Luncheonette. My father is forever telling me what a savvy businessman Eugene is, how lucrative his restaurants are, and how everything he touches seems to turn to gold (in contrast to yours truly here). And one night I was sitting at Amanda’s having dinner with my mom. We were having a long convoluted argument about something…about this stupid incident involving a sister-in-law and a piece of furniture…I’m not going to get into it here. It’s rare that my mom and I ever have arguments of any kind, rarer still that they ever get as heated as this one did.

And at one point, she said to me, “You look just like your father right now.”

And I was like: “Did I ask you to fuck the guy and make me?”

At that very moment, Eugene, who was sitting with some of his employees on a banquette at the back of the room…my mom and I were the last table, and they were all waiting for us to finish so they could get out of there…Eugene, just kidding around, flung a wet tea bag at me, and it hit me with a very audible splat! right on the bald spot on top of my head. And because I was in such a particularly foul, irascible mood, I got up and walked over to King Midas over there and swung as hard as I could and punched him in the head. Thankfully he flinched at the last second, so it ended up just being a sort of glancing shot off the top of his forehead. And I immediately felt enormously remorseful and ashamed — it was really such an awful, reprehensible thing to do (and to a friend yet!) — and Eugene immediately forgave me, because…because Eugene is such a sweet, decent person. He really really is. But none of this would have happened if I didn’t have a genetic predisposition for violence and my father would just stop always reminding me how much money Eugene makes. Unlike a mother and a son, who frequently eschew spoken language in favor of telepathy, a father and son can engage in endless viva voce banter, endless glib small talk about money, jobs, real estate, etc. It’s the sort of reassuring, inoffensive repartee that enables most men to endure — enjoy, even — their stultifying lives of shit-eating servitude. Unlike this casual copraphagia, though, and in the way a bird passes a kind of premasticated ambrosia from her mouth to the mouths of her chicks, mothers try to nourish their sons for extraordinary lives of heroism and martyrdom.

There was a golden age for me when it was just my mother and myself, and this is still the idealized world I long for, still the mythic, primordial time, the paradisiacal status quo ante that I persistently hearken back to, whose restoration is at the core of a mystico-fascistic politics. The world that my mother and I created for ourselves was very refined, and I always thought of everything that lay beyond it as a kind of oceanic sewer. And when I realized that it was no longer possible to maintain the purity, the, uh…the exclusivity of that sublime world, it was…it was very difficult for me…for a very long time. I loved poetry, but suddenly the only poems that interested me anymore were the ingredient lists on cans of dog food and the litany of side effects in pharmaceutical ads. It was as if a witch man from the netherworld was magically eating my insides. Finally, one afternoon, I drank an entire bottle of Novahistine Elixir and melted, one by one, a boxful of my most prized crayons (the ones reserved for my jet-fighter drawings) in the hot steam that issued continuously from the vaporizer in my bedroom — a young valetudinarian’s rite of passage. Then I tried to melt my plastic Civil War soldiers. Would you believe that, after all those years, I still have several of the more grotesquely misshapen ones that I keep in a jar?

But my mother and I have preserved our beautiful closeness. And I think at this stage in our lives, we’re happiest when we’re able to descant upon our grievances and the grave injustices to which we’ve been subjected, happiest when we’re reenacting some tragic event, some traumatic iniquity…something that is for us like the Battle of Karbala is for Shia Muslims or like the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 is for the Serbians.

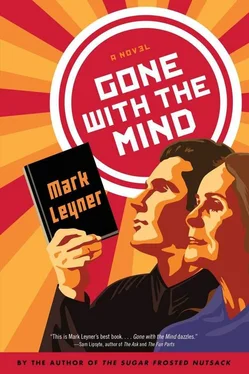

It’s so obvious to me that the fact that I’m going to be reading my book at the food court tonight is meant to evoke the “eating books” of my childhood that my mother spoke about — those books like The Tawny Scrawny Lion or The Musicians of Bremen that she’d read to me as I ate…and I guess I was hoping that Gone with the Mind might, here at this food court, perhaps become the “eating book” of some other withdrawn, delicate, mother-fixated boy…but since you guys don’t seem to me particularly withdrawn, delicate, or mother-fixated— (The fast-food workers don’t react in any way to this.)

And I also think that reading here at this food court is an homage, a kind of…uh…a kind of ceremonial reenactment of those lunches at the Bird Cage at Lord & Taylor that my mom and I used to enjoy, just the two of us, talking and talking…first my mom, and I’d sit there and listen so intently, and then me, and she’d listen and smile…just like tonight, here. You know…in Shakespeare’s play, King Lear says to his daughter Cordelia: “Come, let’s away to prison. / We two alone will sing like birds i’ th’ cage. / When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down / And ask of thee forgiveness. So we’ll live, / And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh / At gilded butterflies.” Isn’t that just amazing?! We two alone like birds i’ th’ cage? That’s my mom and me at the Bird Cage at Lord & Taylor! I mean, c’mon, right? Telling old tales and laughing at gilded butterflies! Right?

Armin Meiwes was a forty-two-year-old computer expert from a small German town called Rotenburg who, in 2001, posted an advertisement on the website the Cannibal Café stating that he was “looking for a well-built eighteen- to thirty-year-old to be slaughtered and then consumed.” Bernd Jurgen Armando Brandes, an engineer from Berlin, answered the notice, and was then, as advertised, slaughtered and consumed by Meiwes.

I really think this kind of consensual cannibalism is such a perfect analogue for the reciprocal relationship between writer and reader, and especially between writers and readers of autobiography. The reader of an autobiography consumes the life of the author, and the author, in turn, consumes the life of the reader, that portion of it surrendered to reading, or listening to, the autobiography.

And you have to admit that it’s pretty interesting that, given all the uncanny correspondences between autobiography and cannibalism, that this reading is taking place at a food court, and that the audience for my work, for the most part, tends to be well built and between eighteen and thirty years old. Granted, it’s a dwindling audience, if the fact that only two people showed up tonight for my reading is any indication…

For the hundred and fiftieth fucking time, we are not here for the reading. We’re on break, dickwad. (MARK smiles sweetly at him.)

Sometimes I’ll stop on the sidewalk to text or tweet something on my phone, and then I’ll finish and look up and — for a moment — I won’t know where I am or even how old I am. If I feel the hot sun on the back of my neck, I’ll think I’m nine and I’m back at summer camp in the Adirondacks. I’m back with that red-haired counselor from Alabama who told me that I was his favorite in the entire bunk, the only “mature” one, and promised to visit me someday at home and take me to the movies. (He did: Yellow Submarine .) And then I’ll sort of snap out of it and realize, Oh, I’m standing here on the street in Hoboken. I’m fifty-eight. And I’ll wonder for a second, What’s the matter with me? Did getting hit in the head with that tea bag exacerbate my chronic traumatic encephalopathy? Do I have a brain tumor or something? Because my mom had a brain tumor, a benign tumor, something called a hemangioblastoma, which she had removed at Mount Sinai Hospital. Thank God it was a completely successful operation, she made a full recovery with no repercussions, no neuropsychological consequences at all. But it was a very tense, very grim moment as they were about to wheel her off to surgery, and I said to the surgeon, I guess to try and lighten the mood a little…I said to him, “Y’know, as long as you’re gonna be poking around in there, in her brain, can you see if there’s anything you can do about how much she talks? I think there might be a switch in there that’s stuck in the on position or something.” And a couple of months after her surgery, to celebrate, I took my mom out to dinner at Raoul’s in SoHo in New York City, and she asked the waiter if there was a discount on the caviar for people who’ve recently had brain tumors. And the waiter said, “Let me check.” Isn’t that fantastic? “Let me check.” First of all, it’s a wonderful question with far-reaching implications. My mother is from the you-don’t-know-until-you-ask generation which believes that people languish in life not because of socioeconomic barriers, but because they are too coy, because they leave the world inadequately interrogated. I also think my mom “suffers” from something one might call Pollyanna’s paranoia, an irrational suspicion that there are people out there secretly trying to do good things to you, that there are all sorts of hidden perks lurking everywhere, almost like the Easter eggs in video games…that it’s possible that Raoul’s might be running some sort of unpublicized hemangioblastoma-all-the-caviar-you-can-eat promotion. (I’m from the never-ask-anything school. I’ll never forget cringing with mortification when my dad asked for coarse-cut Seville marmalade at a fucking Denny’s in Nebraska. I mean, would you ask for an ortolan drowned in Armagnac at KFC? I suppose it can’t hurt, right?) Well, the waiter came back from the kitchen and informed us that, no, there wasn’t such a caviar discount, and he seemed genuinely indignant about it, and he did bring us extra toast points, I remember — it was sort of all-the-toast-points-you-can-eat actually, which earned him an enormous tip, because people just love it when they think a service employee is playing some double game, that he or she has turned against the house and is now allied with you to procure illicit little freebies, even if it’s just extra toast points. Why would we not only believe, but become eternally beholden to some unctuous car salesman who claims to be putting the lives of his own children at risk by throwing in floor mats and a bug deflector? (I know why I would — because I’m so emotionally gullible, so desperate for tiny kindnesses in my misery.)

Читать дальше