You wouldn’t know from my grandfather’s Anglophilic affectations — the rolling of his r ’s (most ostentatiously when providing telephone operators with a number he wanted to reach, always including the exchange name, in this booming, stentorian voice, so everyone within several blocks could hear, “I’d like you to connect me to Henderson thrrree, five-thrrree-seven-thrrree”), the incessant citations of Shaw and Wilde, and the fetishistic touting of various British products (Wilkinson razor blades, Burberry raincoats, Lock & Company homburgs, Boodles gin, Fortnum’s marmalade, etc.) — that this was a man who’d been born in Estonia and brought to Jersey City at the age of one. Although there was one American-made product for which he had a zealous lifelong predilection — those big shiny Cadillacs with the enormous tail fins, the de Villes and the Eldorados. He loved tooling around Jersey City and Deal in a gleaming new Caddie. And he’d say to me, “Markie, my boy, shall we take the Cadillac for a bath?” And I’d jump up and down like a little puppy, because I loved going through car washes, and I still do. I always come out of a car wash in a better mood than I went in with. (And I have to add here, without getting maudlin all over again, that it was while going through a car wash that the Imaginary Intern and I came up with the idea of including my Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory report in the autobiography.) My grandfather had three notorious expressions he used habitually: “If your grandmother had balls, she’d be your grandfather,” “Crept into the crypt, crapped, and crept out again,” and “Let’s not and say we did.” The first one, “If your grandmother had balls, she’d be your grandfather,” was used to preempt any kind of thinking he considered overly speculative. I’m not exactly sure what “Crept into the crypt, crapped, and crept out again” was ever apropos of, but, for me, it spoke of the scatological and the eschatological, and it’s really stuck with me, and if I’m ever asked for advice by young wannabe writers (which, by the way, I will never be), I’d tell them, If you find yourself at an impasse, when you’re stumped, and that, y’know…that blank white page, that empty screen is just sort of glaring back at you, go with scatology and eschatology. You just really can’t go wrong with scatology and eschatology. My favorite expression of his, though, the one I found to be most enduringly evocative was “Let’s not and say we did,” and I remember hoping that someday soon he’d ask me if I wanted to do something (like taking the Cadillac for a bath) and I’d have the gumption to respond “Let’s not and say we did,” using his own pithy demurrer against him (as in the days of nineteenth-century surgery, when un-anesthetized patients, half crazed with unimaginable pain, would leap off the operating table and attack the surgeons with their own instruments), but I never had the heart to do it back then. I was an extremely sensitive little boy. I mean, I was so sensitive that even books— especially books — could cause me terrific apprehension. I would stare up at the books in my grandparents’ living room at 1904 Hudson Boulevard (now Kennedy Boulevard), and almost tremble…shelf after shelf, all the way up to the ceiling, of these august volumes, this wall of books that seemed to lean, to teeter menacingly towards me, as I stood there gazing up, as if at the edifice of a temple, as if it might just crush me with the sheer power of the cultural endorsement represented by these tomes, crush me in the aggregate gravitas of all its exalted, erudite authors, who wielded an intellectual prowess that I could never really even comprehend, never mind possess myself. For some reason, only the encyclopedia seemed congenial to me, within my grasp, and for some reason — and who can really understand the twisted psyches of little children — my favorite thing in the entire multivolume set of encyclopedias, the thing to which I’d return over and over again, with a compulsive regularity, to which I was almost fatally impelled to gaze upon on every visit, was a sepia-toned photograph of an African man with elephantiasis of the testicles who had to walk around with his hideously enormous balls in a wheelbarrow. And sometimes I’d wander over to the credenza where Ray would mix his daily martini, and the long glass rod stirrer he used would seem to me, to this sickly child prone to ear infections, like some sort of Grand Guignol rectal thermometer, another talismanic object that filled me with both dread and desire.

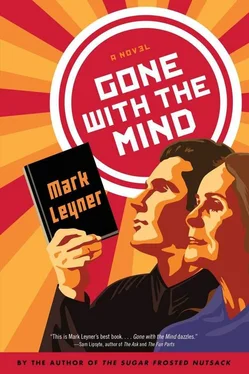

When I slept over at my grandparents’ house, which was only a few blocks away from ours on Westminster Lane, I’d wake up extra early so I could observe his toilette. I was fascinated, I was enraptured by this transformation. I’d watch, with a kind of awed wonder, his production of himself each morning, by the complete sociobiological metamorphosis from the rumpled, musty-smelling little man I’d glimpse emerging from my grandparents’ bedroom into that great, gleaming, redoubtable, fragrant narcissist. He listened to WINS news on a little transistor radio in a calfskin case as he shaved every morning, splashed on his Vétiver, ate his breakfast, and, galvanized by his coffee and his boiled egg into that great man of action, that great public man, emerged later in Journal Square, where common men paid him obeisance and addressed him as Counselor or Consigliere and he greeted them back with his noblesse oblige, rolling his r ’s. He was to me then a splendid, formidable, charismatic sight to behold, a man who’d been known all over Jersey City as someone with the temerity to stand up to the powerful political machine of Frank “I Am the Law” Hague (I was born in Margaret Hague Hospital, the maternity hospital named after his mother), though, there was for me, even at that age, ironically, something of the boss, something of Il Duce about Ray himself. He was most floridly, most grandly and exultantly himself in the piazza. In Journal Square. In public. He seemed to chafe at the constraints of domesticity. We’d drive in his shiny Cadillac past those little canals in Kearny or Secaucus, those iridescent slurries of mercury and PCBs, the classical station WQXR blaring from the radio at head-splitting volume…It’s amazing, isn’t it, how perfectly this big-balled Duce from Estonia steering his gleaming Eldorado with its deafening Puccini past psychedelic streams of toxic sludge presages Mussolini piloting his flying balcony through the polychromatic concourses of this mall at the very end of Gone with the Mind ? It’s amazing how so much of this was already there, intact, back then…how so much of it was already written.

When he got older, he developed a tendency to make these odd, completely gratuitous telephone calls, these peremptory rebukes that would just come out of nowhere. The phone would ring, you’d answer, and, without so much as a hello, he’d snarl, “Why aren’t you watching Golda Meir on Face the Nation, you dumb bastard?!” And he’d hang up. Or “If you’re not watching Itzhak Perlman on Good Morning America, you’re a goddamn moron!” Click. It almost seemed to me that, though he was still alive, Ray was already speaking from beyond, that this was some kind of transdimensional ventriloquism, that he’d thrown his voice into the land of the dead and it had ricocheted back somehow into the mouth of my superego, as my own voice of judgment and accusation. To me there was an undeniable sort of verve or élan to the calls, these batty pranks that were so perfectly punctuated by that concussive hang-up. But there were people in my family— most of the people in my family, I guess — who found these calls particularly unamusing, who thought they were just jarring and mean. But I liked them. I needed them, actually. I really think they helped me get through a couple of rough years…Just imagine standing on a subway platform in the morning, terribly hungover, and some demented person stabs you in the buttocks with an EpiPen, and you’re kind of like, “Thanks.” That’s what it was like for me getting these calls. At the very least, one began to suspect that his mind was chafing at the constraints of his body. But as much as his health deteriorated, he never completely abandoned the piazza, refusing to relinquish his status as a public being, stubbornly performing that role even in its abjection, incorporating all his mortifying indignities, his hydrocele, his colostomy bag, the blend of feces and Vétiver left in his wake, these conspicuous signs of morbidity, without any shame, in fact with a perverse kind of pride and vanity. And though we all cringed and commiserated with each other about how unpleasant and sad it had all become, I find this to be, the more I age and atrophy and putrefy myself, especially in this culture that so valorizes the alleged virtues of youth and health…I find this — Ray’s sad and stubborn “encore”—the more and more that I think about it, to be something splendid, something spectacular.

Читать дальше