But that’s what nonfiction is, people. Shitty feelings and encounters with death. And that’s why we’re here tonight.

The Imaginary Intern once defined autobiography as “a compulsion to share one’s life with strangers on social media.” Along with this compulsion comes a burden of truth…Hölderlin wrote in his poem “Patmos,” “The lords are kind, but while they reign / what they most abhor is falsehood.”…And so, in honor of all the martyrs who’ve died keeping it real, I’d just really like to set the record straight about my mom’s driving — not only does she not drink and drive, she barely drinks at all, and she’s a terrific driver…just a really, really great driver.

And what I mean about honoring all the martyrs who’ve died keeping it real is that people make enormous sacrifices writing nonfiction instead of fiction. I mean, I could have easily concocted something a lot more interesting than an ovarian cystic teratoma for my mom, if that’s what I wanted to do. I could have given her a tumor that…that…I don’t know…a tumor that could sing and dance and act and do impersonations like Sammy Davis Jr. or something. And everyone would have said, “Oh, that’s so cool. How’d you ever think of that? Where do you get your ideas?” Y’know? And as for me — prostate cancer? I mean, c’mon. Prostate cancer has got to be the most boring cancer there is. Seriously. So many men have prostate cancer. If I’d really wanted to give myself some fascinating, bizarre disease, I certainly could have just used my imagination and come up with something…like some weird…I don’t know…some grotesque prolapse or exotic anal fissure that has to be treated with habanero-infused flushable wipes, and everyone would have been like, “Oh my God, magical realism! That’s so cool!” And some people would have been like, “What are you on?” And I could have shot back with Lance Armstrong’s “What am I on? I’m on my bike, busting my ass six hours a day. What are you on?” In other words, I don’t have an exotic anal fissure. And my mom didn’t have an ovarian tumor that could sing and dance and play the drums and that had one eye. And that’s not what we’re all here for tonight at the Nonfiction at the Food Court Reading Series. Tonight’s about reality. Tonight we say death to fiction. And by fiction we mean anything (or anyone) that occludes the forces that really matter. And we also say — and this is something the Imaginary Intern and I used to say to each other before bed:

Death to anyone who opposes the negation of everything that causes us to be dead while alive.

And I just want to say again that I’m extremely proud to have been invited. And, y’know, something occurred to me in the car on the way over here tonight, and it’s that we’re all — each and every one of us — ticking time bombs, potential first-person shooters, mall shooters, whatever…who, given the opportunity to cast off the constraints of petit bourgeois morality, would choose random sadomasochistic chem-sex with hooded strangers over real relationships any day of the week. We live in this crazy, inside-out, totally bizarro world today where, just to give you another example, several large-scale Phase III clinical trials have apparently confirmed the efficacy of fecal transplants in the treatment of social-anxiety disorder. I have a friend who’s a psychiatrist, and I called him recently because I’d been wondering about whether my fondness for chubby women with small breasts was somehow homoerotic — not that it’s something I’m overly concerned about or anything, I was just curious to see what his professional opinion was — and at some point in the conversation he mentioned tangentially the, uh…the funny thing about the fecal transplants.

Look — yes, life is super-trippy. Yes, it may contain intense violence, blood/gore, sexual content, and/or strong language that may not be suitable for children, on-screen defecation, long strings of snot, and sad, sad times…

But, again, I just want to say this:

Nothing else in my life compares to the vitality and plenitude of this moment right now, right here. For me, these plastic chairs and tables are as real an audience as the miners and cowboys Oscar Wilde regaled in Leadville, Colorado, in 1882, or the insensible drunks at the saloon who jeered Granville Thorndyke, the traveling thespian in John Ford’s My Darling Clementine: “To die, to sleep; / To sleep: perchance to dream”…

Oh Thorndyke, you preposterous, undaunted poseur…ever posing as the sad, sad, Ferbered prince…Oh sad, sad, Ferbered prince…sad, sad, Ferbered, oedipally conflicted, impotent prince and poseur…ever posing autobiographically as yourself.

As any mother-besotted son knows, especially the mother-besotted son who is unassimilable in the milieu of his contemporaries, the presence of the mother is simply the cruel betokening of her absence. The mother is the irreducible lack, the hole at the center of it all. And even when we are flying from that, we are flying toward it.

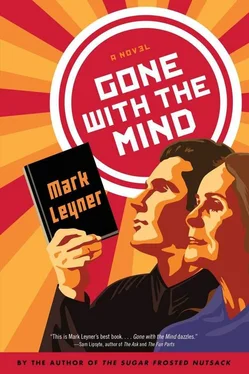

I’ve always thought of my childhood as Edenic, as a distinct kind of paradise (and my adulthood as an expulsion, as a fall), and I still think of Jersey City (circa 1960) as the loveliest place in the world, I still think of it as…as paradigmatically beautiful, with its prewar apartments and Beaux-Arts office buildings, and its pastel, beatific twilights…and infested, as it was, with nuns. And I used to tell people, when I got a little older, that my parents were very much like Rob and Laura Petrie on The Dick Van Dyke Show …very young, sophisticated, very good-looking…although I never really identified much with their son, Richie, who was much too rambunctious and coarse for me. I guess the character, the boy, I identified with most on TV at that time was probably Davey from Davey and Goliath, a Christian stop-motion animated show produced by the Lutheran Church in America and Art Clokey, who’d produced the Gumby series, which used the same type of stop-motion animation, and which I also admired very much. And I felt such a close kinship with Davey because…well…because, I suppose, we were both kids who were motivated chiefly by metaphysical concerns. So I was this sort of mystically inclined, spiritually inquisitive little boy with these very secular, very cosmopolitan parents…I was this little boy who was drawn to transubstantiated things…who was always on the lookout for relics, for some occult talismanic object or dusty amulet…with parents who were more into, y’know, more into Scandinavian furniture and hypermodern fondue forks and things like that. That said, I’ve always recalled my childhood as sublime, as a kind of Eden, as I said. But as I was listening to my mom before — in her wonderful, amazing introduction — it made me begin to remember all sorts of things I guess I’d repressed…I mean, the solitary confinement and sleep deprivation, the force-feeding of beets, the mangled fingers, and the nudity…There’s something very black site about it all. And so, I hope one of the questions we can begin to address here tonight is: What was this childhood? Was it the Garden of Eden or was it Abu Ghraib? Because what begins to emerge here, if all too speculatively, is a whole substratum, a whole buried constellation of petit mal traumas, which orbit around the deepest and the grandest trauma. The death of my first sister registered to me as the loss, the temporary death (in her estranging grief), of my mother. And, of course, loss and abjection are the key motifs in Gone with the Mind. And perhaps the ghost of that little sister (the yūrei, the onryō ) is the Imaginary Intern…or the mall shooter…or the disembodied voice of the Reading Group Guide, which can haunt the margins of a person’s autobiography like a bad conscience.

Читать дальше