“They’re going to start calling him Charlie,” she said.

“They gave him my name ?” I was disgusted.

“Only part of your name.” My mother was excited. “It’s so that he feels comfortable, you know, ‘Charlie’ fits with Callie and Charlotte.”

“You gave him my name,” I repeated.

“It’s more like a junior situation,” my father said, and my mother and Callie laughed.

I did not laugh. And Callie stopped laughing altogether, began to cry, when they told us we would have to move, leave Boston and the block, move to a place that neither of us had heard of. “You’ll love it,” my mother told her, her voice back to measured again.

Beside me, now, in the car, Callie huddled over the strap of her seat belt, the band barely saving her from a wholesale collapse into her own lap. She’d propped a piece of construction paper against the back of a book that she held against her knees, the better to sketch a welcome card for Charlie. My mother asked both of us to make cards but I refused. “What’s the point of giving a card to somebody who can’t read?” I’d asked. But Callie took to the assignment happily, steadily producing a greeting card a day for Charlie over the last month.

For this latest iteration, Callie drew a portrait of our family. First she sketched her own face, then our mother’s. Our father liked to say that Callie and our mother had the same face, heart-shaped, so Callie drew herself and our mother as two loopy valentines. Even though she tried her hardest to be neat, both their heads came out lopsided. Above the crooked lobes of each heart she drew their hair: short spiraling S s, for their matching Jheri curls.

The hairstyles were new. Another thing my mother insisted on changing before the move. At Danny’s His and Hers on Massachusetts Avenue, the hairdresser actually gasped at her request for a cut, to which she replied, defensively, “There won’t be anybody who knows how to do black hair where I’m going. This is the easiest solution.”

My mother had good hair, a term she would never use herself because, she said, it was so hurtful she couldn’t possibly believe in it. But my mother’s hair was undeniably long and thick, a mass of loose curls that Callie and I did not inherit and that she was determined to cut off before we began our new life.

She tried to talk both of us into joining her, but only Callie took the bait. My mother got her with the promise of hair made so easy and simple, you could run your fingers through it. When it was all over, Callie was left with an outgrowth of stiff, sodden curls that clung in limp clusters to her forehead and the nape of her neck and made the back of her head smell like burning and sugar.

Next on the card, Callie drew our father’s face — round, with two long J s flying off the sides. These were the arms of his glasses. She drew his mouth wide and open: he was the only family member who she gave a smile with teeth. And then she drew me. I was a perfect oval with an upside-down U for a scowl. She drew my hair extensions, long thin ropes of braids that Callie charted at ninety-degree angles from my head. She drew the crude outlines of a T-shirt. Then she stopped for a minute, her pencil hesitating. She slyly glanced over at me — she knew I was watching — and then she made two quick marks across the penciled expanse — signifiers for my breasts, recently grown and far too large. A pair of bumpy U s drawn right side up, to match the upside down one she had for my mouth.

“Take them off.”

Callie replied, under her breath and in a singsong, “Breasts are a natural part of the human body, Charlotte. Breasts are part of human nature.” Another of our mother’s mantras, one she had been saying, obviously for my benefit, for the past year and a half. I was fourteen, Callie was nine, and what was a joke to her was an awkward misfortune for me.

Callie put her pencil down, the better to sign to me with her hands: Breasts are a part of human development . Stealthily, I reached over and pinched the fat of her thigh until she took up her eraser again and scrubbed the page clean.

When she’d finished, she reached into the backpack at her feet and pulled out a pack of colored pencils. With thick, grainy streaks of brown she began to color in our family’s skin. She did so in the order of whom she loved the most: our mother, whom she believed to be the smartest person in the world; our father, whom she knew to be the kindest; and, finally, me.

She stopped the nub of her pencil, wavering.

What is it? I signed.

Charlie should be in the picture. She frowned. He’s part of us, but I don’t even know what he looks like.

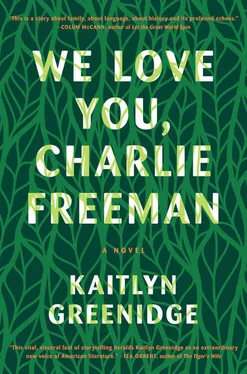

She leaned over the sheet again and cupped one hand close to the paper so that I couldn’t see. When she was finished, she sat up and pulled her hand away. Above each family member’s head was now a trail of three circles, each individual string of thought bubbles leading up to a single swollen cloud with Charlie in its middle. She made the cloud too oblong, she messed it up, so she had to draw Charlie lying down on his stomach. She drew ears that stuck out, a wide, closed-mouth grin; thick monkey lips pressed together, a low-hanging gut, four paws. She gave him a curling tail. Above all of this, in her best longhand, Callie wrote: We Love You, Charlie Freeman.

Too generous, too sweet, so openhearted and earnest it stung. I curled my lip, turned away, watched the trees rush by instead.

We were still the only car on the road and my mother was driving fast. Me and Callie had only been this far from the city once before, the previous summer, when our parents sent us to a black, deaf overnight camp in the backwoods of Maryland. They said it was to improve our signing, but I think it was to make sure we would find friends. In Dorchester, our constant signing, our bookish ways and bans from fast-food restaurants and booty music, assured that me and Callie were unpopular on the block. At the camp, the hope had been that among others who knew our language, at least, we would find a home. But it didn’t work out that way.

That past summer, Callie and I braided plastic gimp bracelets that only went around each other’s wrists. We made yarn God’s Eyes that were never exchanged with anybody else, that followed us home to gaze sullenly from the kitchen window over the sink. It was quickly discovered that we could hear and did not have deaf parents. The other campers were black like us, but they were truly deaf and suspicious of our reasons for being there. Except for a few spates of teasing, they left the two of us alone.

At that camp I’d learned a host of new signs — for boobs , for shut up , and for suck it . But the most dangerous thing that camp had taught me was the awful lesson of country living: out there, in the open, in the quiet, all the emptiness pressed itself up against you, pawed at the very center of your heart, convinced you to make friends with loneliness.

I leaned my head against the window. Through the glass, I heard a steady whine, wind sliding over the car. I secreted my fingers into my lap and began to finger-spell — all the dirty phrases I’d learned the summer before, all the rough words that had been thrown my way, spelled out on the tops of my thighs, protection from that low whistle of wind moving all around us.

I fell asleep to the blur of a thousand trees. When I woke up, the radio was still on, but only every third word came through. The rest was static.

“Turn it to something else,” I called, but up front, my mother shook her head.

“There is nothing else.”

Everything outside the car was a belligerent green. Just below my window a thin streak of stone skimmed along, the same height as the highway posts. As we drove, the gray crept up through the undergrowth until it revealed itself to be a thick, granite wall the height of our car. Then in one abrupt swoop it towered over us, the very top edged with a trail of glittering sunlight — the reflection of hundreds of shards of glass, scattered razor side up in the cement.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)