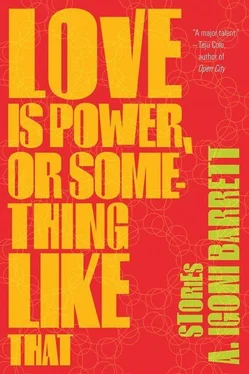

He parted his lips to speak, but at that moment a wild cheer burst from the barroom, drowning out everything. Manchester United had scored.

When the celebration ended, I repeated my question. “Because,” Babasegun said, drawing out the word. He breathed in, breathed out, slow and steady. “She will soon put me in trouble. She’s fucking everybody, small boys, big men, even some of my friends. The way she’s going, she will soon catch something. She has aborted two times already. If she gets pregnant again, how will I know it’s mine?”

“That bad?”

“Yes, she is. Rotten.” Then he added quickly: “She was already that way before.”

My curiosity was piqued by this spoiled young thing hidden away in a dead-end town. I wondered what she looked like, wondered how wild she really was. I wanted to know her.

“Let me help you,” I said, and smiled at Babasegun, my cheeks aching with stiffness. “Let me take her off your hands. Let me make her forget you. Introduce me.”

Babasegun threw back his head and laughed. His cheekbones swayed, his tribal marks shifted, his foot knocked my shin under the table. He poured beer and drank, wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. “Bad boy!” he said, slapping the tabletop, rattling the bottles. “I knew you liked women, I knew you were my kind of guy. My man! ” He stretched out his arm and we bumped fists. Then he turned serious, said:

“If I introduce you, forget it. She’ll never do anything with you. She’ll think I sent you to trap her. The only way you’ll get her is on your own. But I can help.”

He gave me her mobile phone number and told me the best way to approach her. Be upfront about what you want, he said. Don’t woo. Tell her to come and see you at your hotel.

That night, when he dropped me off at the hotel gate, I leaned into the passenger-side window and thanked him for being a good friend, one willing to share his beer and his girl. Then I asked the question.

“Are you sure you’re through with her? You’re sure you won’t go back?”

“I’m sure,” he said. “I’ll never go back.”

The following day, after my class, about three o’ clock, I called her.

“Hello? Who’s this?”

“My name is Iggy. Is this Joke?”

“Yes.”

“Hello, Joke.”

“What do you want?”

She sounded different than I’d imagined. Colder, bolder. My heartbeat quickened. Her voice was attractive, husky and refined. Not your average small-town girl’s.

“Actually, erm, I’m new in this town.” I coughed to clear my throat. “I got your number from a friend who met you when he passed through here some months ago. He said you’re a nice person to hang out with.”

The phone line crackled, sounding like Babasegun’s car player when the tape ran out.

“Joke? Are you there?”

“What’s your friend’s name?”

The fierceness in her voice caught me off guard. I said the first name that came to mind.

“Chinua. His name is Chinua.”

Bush-fire static. I could feel the gears clicking in her head.

“I can’t remember any Chinua from out of town,” she said. Her voice softened, took on a faraway quality. “Chinua, Chinua. . no, I don’t think I’ve met any Chinua who doesn’t live here. Are you sure that’s who gave you my number?”

I released a long hiss of breath into the phone. “I got your number from a friend, and his name is Chinua, that’s all. Can you come and meet me?” I said the name of my hotel and my room number. “There’s something important I want to discuss with you.”

“What is it?”

“Not on the phone.”

“All right, when do you want me to come?”

I tried to speak but my throat was dry. I held the phone away from my mouth and coughed till I tasted rawness. I dabbed at my eyes with my knuckles, then raised the phone and said, “Come now.”

“Today?”

“Yes. I’m waiting for you.”

“Well, I’m not far from your hotel,” she said. Short pause. “Give me an hour.”

I was standing in the bathroom doorway when the phone line went dead. I walked to the bed, sat at the edge. One hour. Joke. Babasegun was right. He was a stand-up guy, he had delivered. A song rose in my head. Somebody wake me I’m dreaming.

The TV showed NN24. I pointed the remote control, changed the channel to MTV, and then raised the volume until the walls vibrated with music. On the screen, Lady Gaga in an Andy Warhol fantasy. Sterile. I glanced around: the room was a mess. I rose, swept everything off the bed — my dirty clothes, the pile of porn DVDs I watched at night on my laptop, the two books I’d brought along but hadn’t yet begun reading, the TV remote control, and my skin lotion — and arranged the sheets.

The next evening, Babasegun called my phone to give directions to a new bar, where we agreed to meet at seven. This was the third time he had phoned me, and I could tell he was more comfortable spending money on beer than on phone credits. He had so far refused to let me pay for my drinks; he always picked up the tab. On the phone he spoke in a rush, his greeting curt and his sentences short. Rude. He dropped the call while I was still speaking.

I left my room at a few minutes to seven and flagged down a motorcycle taxi in front of the hotel gate. I arrived at the rendezvous four minutes late. The Saab was parked by the roadside. The bar was outside. It was smaller, seedier, and more exposed than the bar opposite my hotel. Babasegun sat on a long wooden bench, which he shared with two men. He smiled when he saw me. He wore a tailor-made shirt in green and yellow nsibidi print. There was an opened bottle of Trophy on a stool in front of him. An empty bottle lolled at his feet.

“I don’t like this place,” I said as I settled beside him on the grime-patinaed bench. “Let’s stick to the bar near my hotel. I’m sorry, I know you want to show me around, but I really need to settle that Wunmi business.”

Babasegun looked at me with surprise. “What about Joke? I thought you met her yesterday?”

“No. She didn’t come, she stood me up.”

“Are you serious?”

“Of course I’m serious.”

Babasegun drank from his glass, wiped his mouth backhanded. “That’s strange, very strange,” he said under his breath. His hand palmed his scarred cheek in slow circles. “You sure she didn’t find out that you know me?”

“I don’t know. If she did, it’s not from me. I called her, we spoke, and we agreed to meet. She did not show up. I’ve been calling her since last night to find out what happened, but she’s not answering—”

I stopped and listened; the hairs at the back of my neck prickled. I turned around to find an old woman standing close, watching me. Her eyelids were black with kohl. Her cotton-white hair was cornrowed. Her stringy arms, which rested akimbo on her hips, were covered with crude tattoos of names, dates, the birth details of her brood. Under the smell of mothballed fabric she gave off, I caught a whiff of catfish guts.

“Yes?” Babasegun said.

I waited for her to speak, then realized he was waiting for me.

“Yes what?” I asked, and, in a whisper: “Why is she staring at me?”

“Iya owns this bar. Tell her what you want to drink.”

I avoided her red, tired eyes. “Trophy,” I said. She made no move to leave.

“Iya’s catfish peppersoup is the best in town,” Babasegun said.

I nodded. He addressed her in Yoruba. She walked away.

Читать дальше

![Сьюзан Кейн - Quiet [The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking]](/books/33084/syuzan-kejn-quiet-the-power-of-introverts-in-a-wo-thumb.webp)