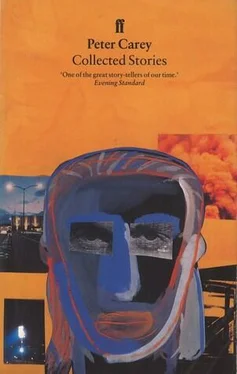

Peter Carey - Collected Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Carey - Collected Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1996, Издательство: Faber and Faber, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Collected Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Faber and Faber

- Жанр:

- Год:1996

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Collected Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Collected Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Collected Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Collected Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I asked you if you were frightened to die, now. You smiled and said nothing.

I asked the question to stop you smiling.

I don’t know who you are. You have not stopped smiling since I found you at Villa Franca. You have not stopped smiling except to make love, and then you frown, as if you had forgotten what you were going to say. Your smile is full and gentle. It is a smile of softness and of complete understanding but you refuse to explain it and I do not know what you understand and you continue to refuse me this.

You wish for more yoghurt. Again, for the eighth time today, we leave this room and go to the café opposite the Restaurant Centrale. You eat yoghurt. I watch. The soldiers who sit at the other tables watch loudly. They watch us both. You frown, as if making love, eating yoghurt. I cannot bear the sight of it, the yoghurt, the texture of it is repulsive to me, like junket, liver, kidney, brains, Farax, and Heinz baby foods.

Your yoghurt finished, you look at me and smile. Your eyes crease around the edges. The strange thing about your smile is that it has never once become less real or less intense. It is a smile caught from a moment in a still photograph, now extended into an indefinitely long moving film. You look around the café. I tell you not to. The soldiers are not schooled in the strange ways of your smile and may misinterpret it. They have already misinterpreted it and sit at tables surrounding us.

If Timoshenko dies they will rape you and shoot me. That is one possibility, have you considered it?

I watch the spider as it crawls up your arm and say nothing. You know about it as you know about many things. You insisted on going through the border post ten minutes after me. Is it for that reason, because of your inexplicable behaviour, that they held you there so long. I saw, through the window of the verandah, the officials going through your baggage. They held up your underwear to the light but did not smile. Things are not happening as you might expect.

I wish you to frown at me. What would happen if I asked you, gruffly, to frown at me here, in public? You would smile, suspecting a joke.

When the soldiers see us walking towards the café they call to us. I ask you to translate but you say it is nothing, just a cry. They wait for us to come and eat yoghurt. It is a diversion. While they remain at the café there cannot be a general alert. For that reason it is good to see them. They, for their part, are happy to see us. They call out “Yoguee” as we walk up the hill towards them. When we arrive at the table there are two bowls of yoghurt waiting. For the third time I send one bowl back. The waiter refuses to understand and jokes with the soldiers. You say that his dialect is difficult to catch. It is a diversion.

The heat hangs over the town like a swarm of flies. Trucks rumble over the old stone bridge. It stinks beneath the bridge. If you couldn’t smell the stink by the bridge the scene would be picturesque. I have taken photographs there, eliminating the stink. Also a number of candid shots of you. I wish you to appear pensive but you seem unable to portray yourself.

There are some good dirty jokes concerning the Mona Lisa’s smile and the reasons behind it. Your smile is not so enigmatic. It is supremely obvious. It is merely its duration that is puzzling.

I do not know you. Your accent is strange and contains Manchester and Knightsbridge, but also something of Texas. You have been to many places but are vague as to why. You have no more money but expect some to arrive at the Banco Nationale any day. We wait for your money, for Timoshenko, for night, for morning, for the ceiling to rumble and the water to pour down. I have put newspaper in the bidet to stop the water from the ceiling splashing. I have begun a letter to my employers in London explaining my absence and there is nothing to stop my finishing it. I have hinted at a crisis but am unable to be more explicit. They, for their part, will interpret it as shyness, discretion, or the result of censorship.

At this moment the letter lies conveniently at the top of my suitcase. If the suitcase is searched the letter will be found easily. It is possibly incriminating, although it is constructed so as to reveal nothing. Knowing nothing, it is possible to reveal everything. That is the danger.

Night

It is night. You lie in the dark with your face hidden in the pillow. You lie naked on top of the blanket; you like the texture of the blanket. It is hot and the blanket is grey and I lie beside you on the sheet, peering at the light entering the room through closed shutters. I have considered it advisable to keep the shutters pulled tight — the room is at street level and has a small balcony that juts out a foot or two above the cobbled roadway.

I touch your thigh with my toe and you make a noise. The noise is muffled by the pillow and I do not understand it.

I sleep.

When I wake you are no longer there. My body is electrified by short pulses of panic. The shutters arc open and a truck drives by, beside the balcony and above it. I hear the driver cough. Men in the back of the truck are singing sadly and softly. I listen to them hit the bump at the beginning of the bridge and hear the hard thump and clatter. The sad singing continues uninterrupted, as if suspended smoothly above the road.

You are no longer there. I dare not look for your bag, but you have left a handkerchief behind. I could rely on you for that, to leave small pieces of things behind you.

It is not the money. I am not concerned with the money. The Banco Nationale has not impressed me with its efficiency and I have no faith in its promises and assurances. They cashed your last traveller’s cheque and gave a hundred U.S. dollars instead of ten. You laughed and took the money back, but not from a sense of caution.

In the bank there was an old woman in black who had her money in a partially unravelled sock. You stood behind her and smiled at her when she turned to stare at your dress. If the money were to arrive in an old sock I would have more confidence, but you say it is coming from Zurich and I have little hope. No, it is not the money, which we both undeniably need. The panic is not caused by the thought of you disappearing with or without the money, nor is it caused by the thought of the secret police, although I am not unconcerned by them.

But the panic is there. I fight it consciously. In my mind I rearrange the filing system in my London office. There are some red tabs I have been anxious to order. I busy myself writing classifications on these red tabs. I write the names of my districts: Manchester, Stockport, Hazel Grove. At Hazel Grove I lose my place. I lie on the sheet covered by small pinpricks of energy and hear a man shout something that sounds like “Escribo”. I am sure he could not know the sign on the door of our room. Unless you have told them, and they have shouted it deliberately, to frighten me. For you say nothing of the police or the political situation when I attempt to discuss it. As for the newspapers, you say they are boring, not worth translating, and that, in any case, they are unlikely to report Timoshenko’s death immediately. You say you have no idea why they would not let us back across the border last Sunday and claim that you accept their story as reasonable and correct. You have also suggested that it was because “the border closes on Sunday” but that was not a very good joke. And, by now, it is essential that we wait “until my cheque comes from Zurich”. You seem bemused, as patient as a sunbather.

Is it because you want to see the ending, how the story works out? Because I remember the way you were in Riano when we went to the cinema to see that American film, something about the F.B.I. You laughed continually and the audience made small hissing noises at you. But you waited, because you wanted to see the end. Then we went to a café for a drink and you sipped your sweet vermouth and said, “Wasn’t it awful?”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Collected Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Collected Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Collected Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.