Of course no one does.

He turns around and starts walking to the plaza. He passes vans with signs saying Sonsonate and Zacatecoluca before he sees the bus that will bring him back to San Salvador. Overcome by disappointment, tears edge out of his eyes.

When he reaches the bus, the door is open but the driver is still not there. Why should he go in and wait in the heat and smell the accumulated body odor that probably hasn’t been washed off for days?

Guillermo feels a tap on his shoulder and ignores it. Why would anyone want him? Maybe it’s Archangel Michael ready to accompany him to his grave.

He feels a second tap and turns around, annoyed. He sees a woman wearing a black-and-white cotton keffiyeh on her head. The scarf hides her nose and mouth. He glimpses green eyes and thick black eyebrows — a familiar sight, but aged with sparrow’s feet. He can’t speak — what could he say from his choked throat?

“Señor,” the woman whispers.

Guillermo’s not sure what he’s seeing.

She begins unwinding the scarf from the base of her shoulders. He recognizes clumps of black hair that is cut short, almost like a pageboy. Oh my God , he says to himself, convinced he’s not hallucinating. God is not unjust, a trickster intent on fooling him — it’s Maryam, somewhat aged, with much shorter hair! “I can’t believe it’s you,” he says to her, leaning in to kiss her forehead.

“Por favor, señor,” the woman says, backing away from him. “If you aren’t getting on the bus, could you at least get out of the way? This bag is very heavy.”

Guillermo closes his eyes, overwhelmed by his mistake. His whole life has been a mistake. He has always opted for the easy solution. He has always felt deserving. He is deserving.

It can not have been an accident he wasn’t shot. People can escape their fate.

“Por favor,” he hears the woman repeat.

He can’t even look back at her. Somehow his legs have climbed up to the first step of the bus. He grasps the edges of the doors and with great effort pulls himself up.

What a mistake to have come.

His legs wobble, about to give under him. He has always had strong legs, but he stopped exercising in San Salvador, and muscles atrophy quickly. He barely makes it into a seat before he collapses.

He is sweating profusely. His blue shirt has mackerel and catfish emblazoned on it. At this moment it’s thoroughly wet, as if he has just stepped out of the ocean.

He realizes he’s on the bus to San Salvador, on his way back to his apartment and his solitary life. He has much to expiate: his foolishness, his years of blundering and wastefulness, the pettiness of so many of his actions, and the devastating comprehension that he does not deserve Maryam, whether she is alive or dead.

Guillermo curls into his seat, placing his head against the bus window. He closes his eyes and tries to calm his breathing. He is trying to even his breaths, as he did during the weeks he practiced pranayama yoga: dispel all thoughts and concentrate on the soft point of light issuing from a blue cloud of emptiness. He feels the bus throttling along and hears ranchera music and laughter. He falls asleep.

He dreams he had met Maryam in La Libertad. In the dream she drags him by the hand to a restaurant with lime-green walls and red-tiled floors with four empty tables. It is off the beach and empty.

They take a corner table near two large windows overlooking empty lots across a muddy street. An overhead fan sputters. As soon as they sit, a boy wearing a torn T-shirt brings them a menu.

Maryam tells the boy to bring them a basket of chips with guacamol and two Supremas. Before the boy is out of earshot, Guillermo screams, “Frías como los muertos! ” As cold as corpses !

Guillermo takes hold of Maryam’s hand. It is darker than before, but just as smooth and lithe. For a few minutes they sit in silence staring at each other, memorizing each other’s faces.

But something spooks him and he pulls his hand away as if they are in Guatemala and someone might catch them in a moment of intimacy.

The boy brings the beers and the chips.

As Maryam grabs her bottle, Guillermo notices that she’s still wearing Samir’s wedding ring.

“I wear it out of habit,” she says. “It doesn’t mean a thing.”

* * *

When Guillermo wakes up, the bus is approaching the San Salvador terminal.

As he pulls himself out of his seat, he hears a soothing female voice say, “Inshallah.”

Guillermo couldn’t agree more.

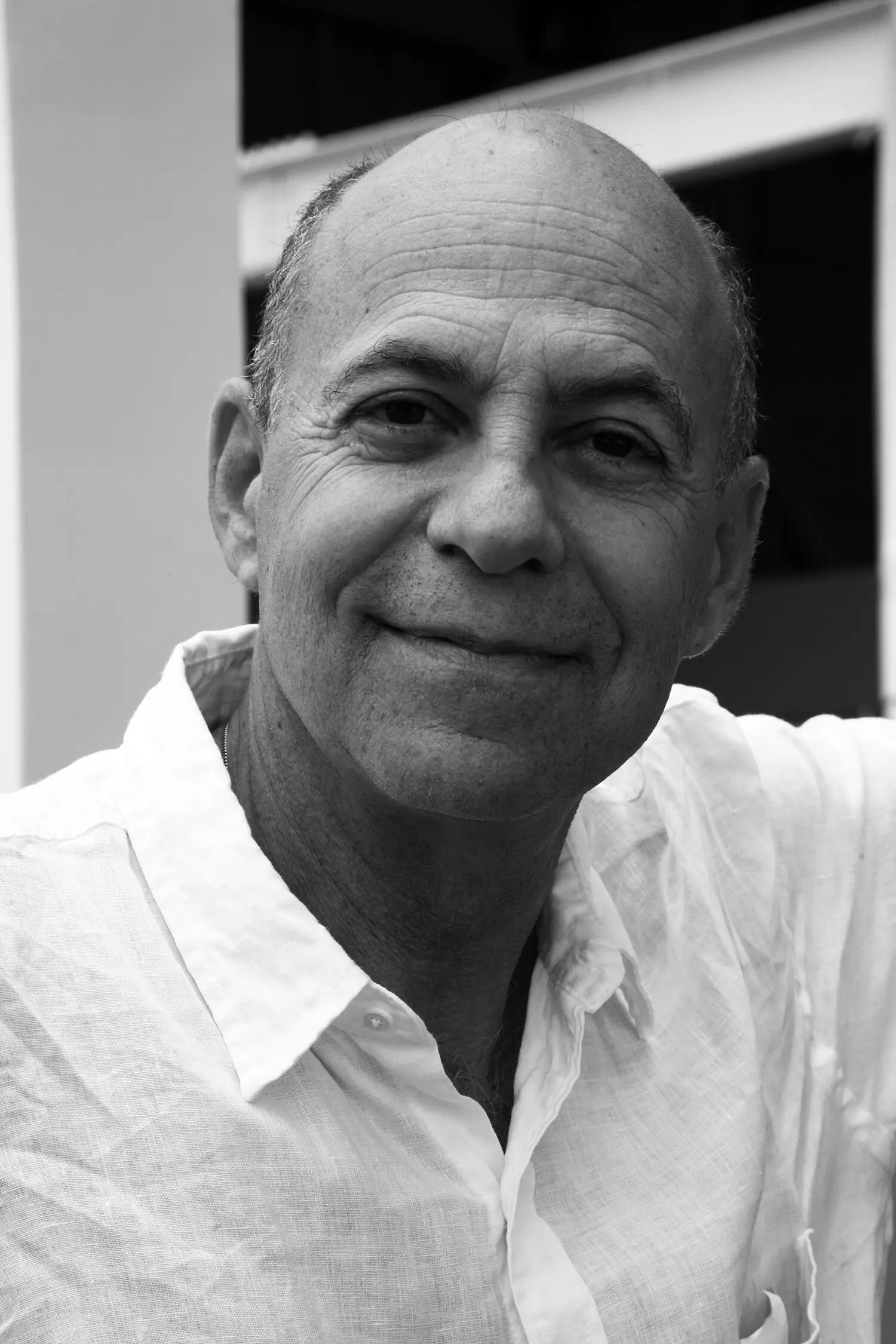

Guatemalan novelist DAVID UNGER was awarded his country’s Miguel Ángel Asturias National Prize in Literature in 2014, despite writing exclusively in English. He is the author of the novels The Price of Escape and Life in the Damn Tropics. His short stories and essays have appeared in Words Without Borders, Guernica, KGBBarLit, and Playboy Mexico . He has translated fourteen books from Spanish into English. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Land of Eternal Spring

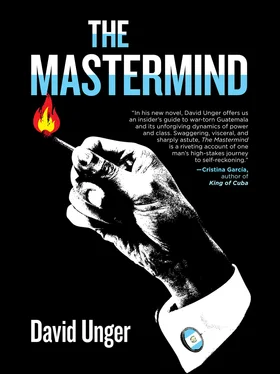

I decided to write The Mastermind for two reasons: 1) After publishing four novels treating different aspects of Guatemala’s history, I wanted to write a book that dealt with Guatemala’s contemporary reality; and 2) I was intrigued by the internationally reported 2009 Rosenberg case in which a lawyer makes a recording accusing Guatemala’s president of engineering his murder (see David Grann’s New Yorker story about it), though I was extremely dissatisfied by the popular notion that this event proved that “life is stranger than fiction.”

To a large extent, Guatemala is a clear example of a failed state. Murder, corruption, femicide, rape, and gang warfare are so rampant that many citizens have lost hope; this in a country with spectacular volcanoes, colonial cities, and first-rate Mayan ruins visited and enjoyed by nearly two million tourists a year. How can these two realities coexist? Is there such a thing as distinct parallel universes?

The Mastermind is both the love story of Guillermo Rosensweig and Maryam Khalil and an exploration of corruption and impunity in Guatemala. My intention was not to write a captivating thriller, but to reveal the inner mechanism of the corruption that can and does exist in Guatemala and in which there are various, morphing puppet-masters. I wanted readers to identify with the protagonists, but at the same time offer them varied readings and interpretations of what appeared to be happening. But most of all, I wanted to write a good, solid story incorporating unexpected twists, leaving readers more informed about themselves and the social and cultural complexity of a country not that different in many ways from the United States.

— David Unger