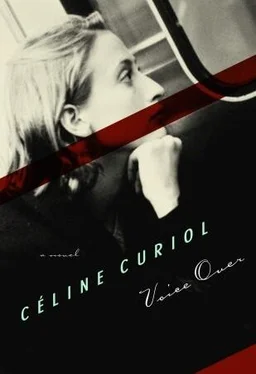

Céline Curiol’s first novel, Voice Over , written when the author was in her late twenties and published just after her thirtieth birthday in 2005, is a rare and unforgettable book, one of the most stirring literary debuts I’ve come across in recent years.

What distinguishes Curiol’s writing is its uncanny fluidity and masterful control over multiple stylistic effects. The reader is both inside and outside at the same time, immersed in the inner life of the central character and yet vividly aware of the world that surrounds her as she floats through an all-too-real present-day Paris, a city that presses down on her throughout the novel with all the force of a dream. The main thrust of the story concerns the adventures of this nameless young woman, but Curiol’s eye for detail is so sharp, so exact in its renderings of the world beyond her character’s skin, that even as the narrative concentrates on the actions of a single individual, we are simultaneously given a crystal-clear picture of French society at large — the new France, the France of the early twenty-first century. Much of the book’s mordant humor is lavished on the hypocrisy, irrationality, and outright absurdity of the social arrangements, class differences, and no-so-buried racism the heroine sees around her.

Voice Over is a story of obsession, alienation, and a descent into near madness. The central character, who works as a public address announcer at the Gare du Nord, falls for a man who is attached to another woman. Slowly and inexorably, something begins to happen between them — or almost. Such is the not so terribly complex plot of this deeply complex novel. Meanwhile, hundreds of events, both large and small, are recounted as Curiol’s damaged and poignant heroine goes about her life, which is filled with numerous random encounters with people as diverse as a female impersonator named Renée Risqué, a forlorn African immigrant, a photographer with the delicious name of Olivier Chedubarum, and an actress who happens to have the same name she does. Curiol’s prose moves with the emotions of her character, from the precise, clinical tone of an empirical observer to the opulent, disjointed streams of thought assaulting a mind in the grip of hallucinations. In one startling passage toward the end of the book, as the heroine rushes desperately from her apartment to catch a subway that will take her to the train station, her frantic state is beautifully matched by the frenzy of Curiol’s writing. “She puts on the clothes she finds on the floor, then her coat, slings the sports bag and her handbag over her shoulder, looks for her keys, hears objects dropping to the floor without knowing what they are, finds her keys on the kitchen table, battles with her feet and shoes to get the former into the latter, glimpses 8:15 somewhere, opens the door, locks the door, rushes down the stairs into the street, quick glance to the right, to the left, hesitates, searches her mind for the shortest route to the station, begins to run.” On the next page, as this race against time continues, we come to one of the most astonishing sentences in the novel: “Her métro pass isn’t in her bag, her métro pass is in her bag.” Thought is perfectly wedded to action here, and only a brilliant, daring artist would have the wit and courage to come up with such a formulation.

I admire this book for its grace and economy, for its vigor, compassion, and often humorous turns. Curiol pulls us into her narrative with the assurance of a veteran storyteller, and after only a few pages, we are already deep into the novel. Without the slightest shred of sentimentality, she explores the innermost crevices of her heroine’s soul to create a fully realized portrait of a human being — a person of manifold contradictions and impulses, a figure who embodies both the tragic and the comic in ways seldom seen in contemporary fiction.

Take note. A superb new writer lives among us.

— Paul Auster

Yes, it is rather an ambiguous voice and not always easy to follow, in its reasonings and decrees. But I follow it none the less, more or less, I follow it in this sense, that I do what it tells me. And I do not think there are many voices of which as much may be said. And I feel I shall follow it from this day forth, no matter what it commands. And when it ceases, leaving me in doubt and darkness, I shall wait for it to come back. .

Samuel Beckett, Molloy

They have known each other for a long time. She has never quite been able to recall the moment when they met, the place, the precise day, whether she shook his hand or they kissed on the cheek. Nor has she ever thought to ask him. She does have a first memory, though. As she was climbing into her coat in the narrow hallway of an unkempt apartment, she had caught his look of distress. The woman he had flirted with all evening was refusing to leave with him. He was trying to persuade her with an insistent barrage of words, which fell to pieces in the face of the majestic creature. She thought the idea of being suddenly deprived of the object of his affections must have been more than he could bear just then. And seeing him this way, in love, had moved her. She had slipped between the two of them and said, I’m off. But he had not replied.

She still remembers his hair and his hands. In her mind, she retains a distinct image of their thickness and color, their size and shape. Because to touch these parts of him is perhaps what she most spontaneously desires, is what for her would open up the path to intimacy.

In the window of the wine shop, each bottle has been set at a slight angle to those on either side. No prices are marked on the labels; she decides to go in. In order to help her with her choice, the man behind the counter wants to know what dishes will be served at dinner. She doesn’t dare tell him that they won’t be eating, she fears he’ll take her for an alcoholic. I’ve been invited, I haven’t been told anything, she says, improvising an answer to counter the hint of reproach dawning in the man’s eyes. I’ll take some white and some red, I suppose, she adds by way of conclusion. He picks out three bottles; she accepts at once. He wraps them in shiny paper, sets them down vertically in a bag. Back outside, she walks along with the promising clink of glass in her arms.

She has sat down at a deserted outdoor café. From the heights of his elongated spine, an ashen-faced waiter takes her order while checking to see that nothing has changed on the terrace of his little domain. The espresso arrives with the bill. The coffee is cold and bitter. In spite of her exhaustion, she has no intention of missing the party: that would show she was unworthy of his friendship. No doubt one of the guests will have remembered to take along candles. It would be a shame if he had nothing to blow out, no wish to make, no icing to lick off the little plastic holders — he who is so keen on celebrating his birthday. Honoring a person’s arrival into the world has never seemed to make much sense to her, but in his case she can understand. What is a birthday? A mark on time to reduce it to human scale. The waiter is closing up the cash register, he wants his coins. The palm of his hand is a tracery of jumbled lines imprinted by hundreds of adroit, repeated actions everyday. All of a sudden, she has an urge to put something on it other than metal, perhaps her own hand.

Her apartment smells of varnish and incense. She takes the bottles out of the bag, lines them up on the kitchen table. A moment’s hesitation, and then she opens the bottle of white, pours herself a glass, and waits for the time when she will go to his house.

Читать дальше